Simply stated, situation rooms use play and game-based practices to proliferate imaginaries. Using the basic tenets of play – a specific space and time, a series of (factual and self-imposed) constraints, and chance – situation rooms generate a temporary heterotopic condition conducive to exploration.

Situation rooms, and play and games in general, have a long history of being used in arts and design. Critical theory has consistently construed play as a necessary condition for the generation of culture and as a crucial process in human cognitive development. Since the trailblazing work of Johan Huizinga, pioneering authors have definitively disconnected play and games from their traditional association with frivolous or inconsequential activity. Following the spirit of these authors (if not always their statements), we claim that play is so relevant that it should be conceived as a way of relating to the world rather than a sub-set of ‘childish’ activities that can be isolated and treated accordingly.

Other fundamental aspects notwithstanding, we are particularly interested in the generative value of play: play may be used as a way of transforming reality. We can understand play as addressing three basic themes: limits, self and chance. These refer, respectively, to the way we construe an understandable order of the world (how we establish physical, temporal and normative limits to define a specific subset of actionable reality in order to deal with it), the way we construe ourselves (how we construct our own selves in relation to others) and the way we construe the unobservable or hidden forces of reality (how we deal with asubjective agencies). Play, then, simultaneously addresses the objective, subjective, and asubjective realms. This threefold capacity of play to define limits, test and expand the self, and address chance makes it a perfect ally for all design-based disciplines, whose primary aim is to transform our world, imagining and projecting other realities. The relationship between play and design is a very strong one, and one worth exploring in a radical way. Indeed, thanks to their simultaneously regulated and exploratory nature, games and play can be harnessed to fuel the disruptive capacities of design.

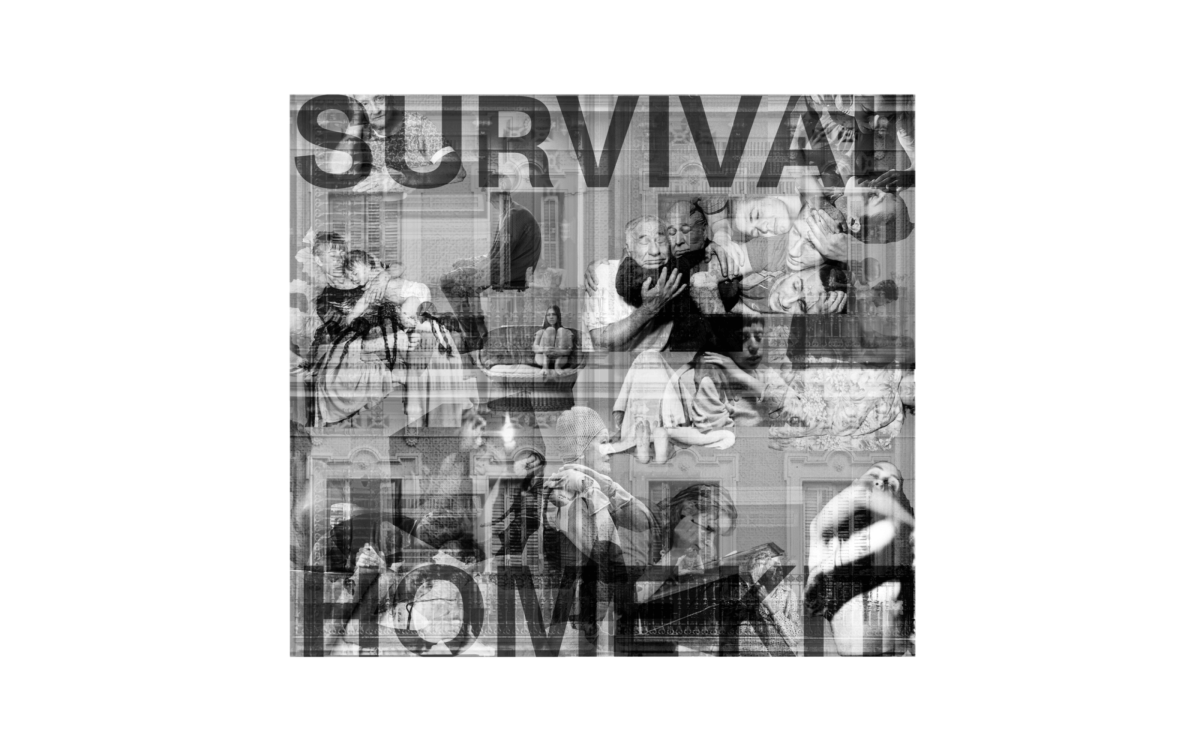

An expanded notion of play holds an incredible potential for design. We can summarise the contribution of play to design in three concepts that mirror the triad of play’s pursuits: constraints (facilitating an exploratory use of factual or self-imposed constraints); engagement (prompting new types of engagement and authorship); and chance (creatively embracing chance). Coupling pragmatic efficacy with visionary criticality, combining its role as solution provider and as a problematising practice, design can further its relevance as a practice that simultaneously contributes to proposing solutions and posing questions that help address significant societal, technical and cultural issues.

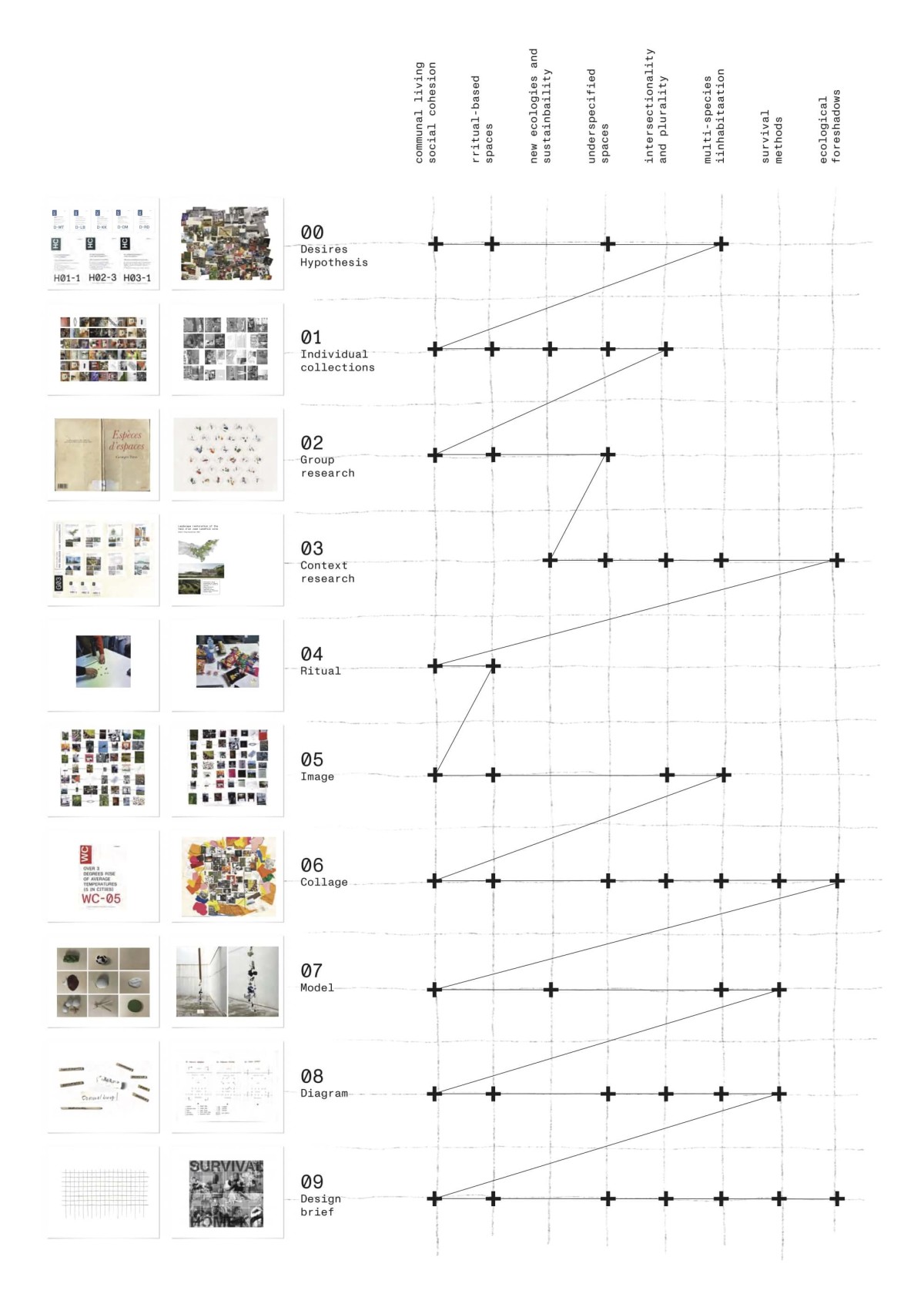

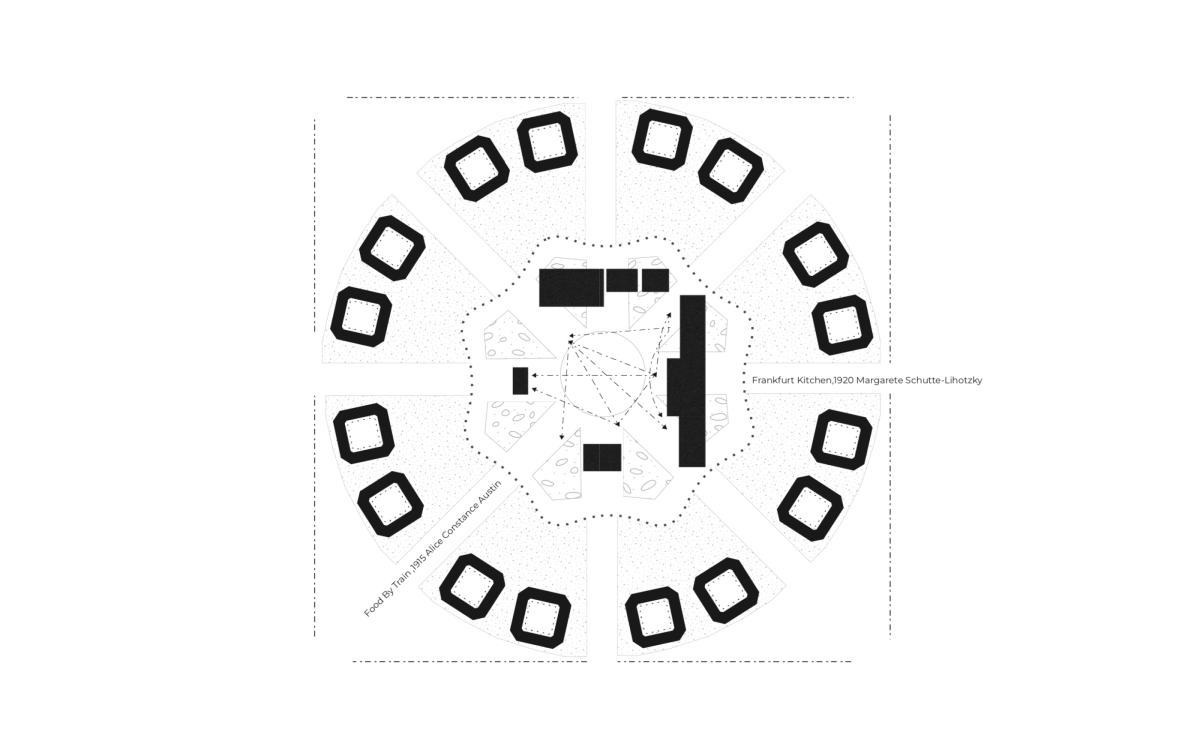

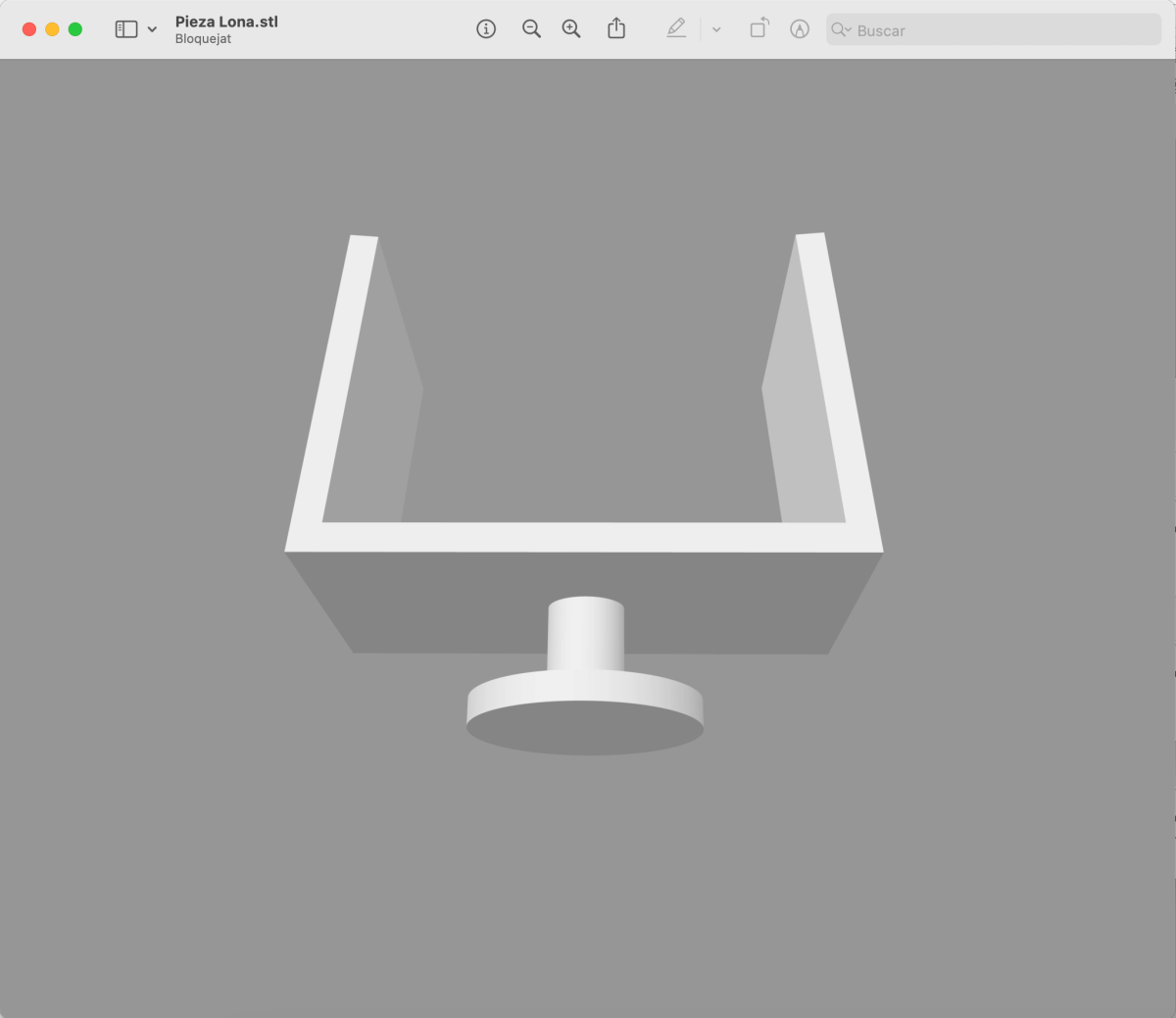

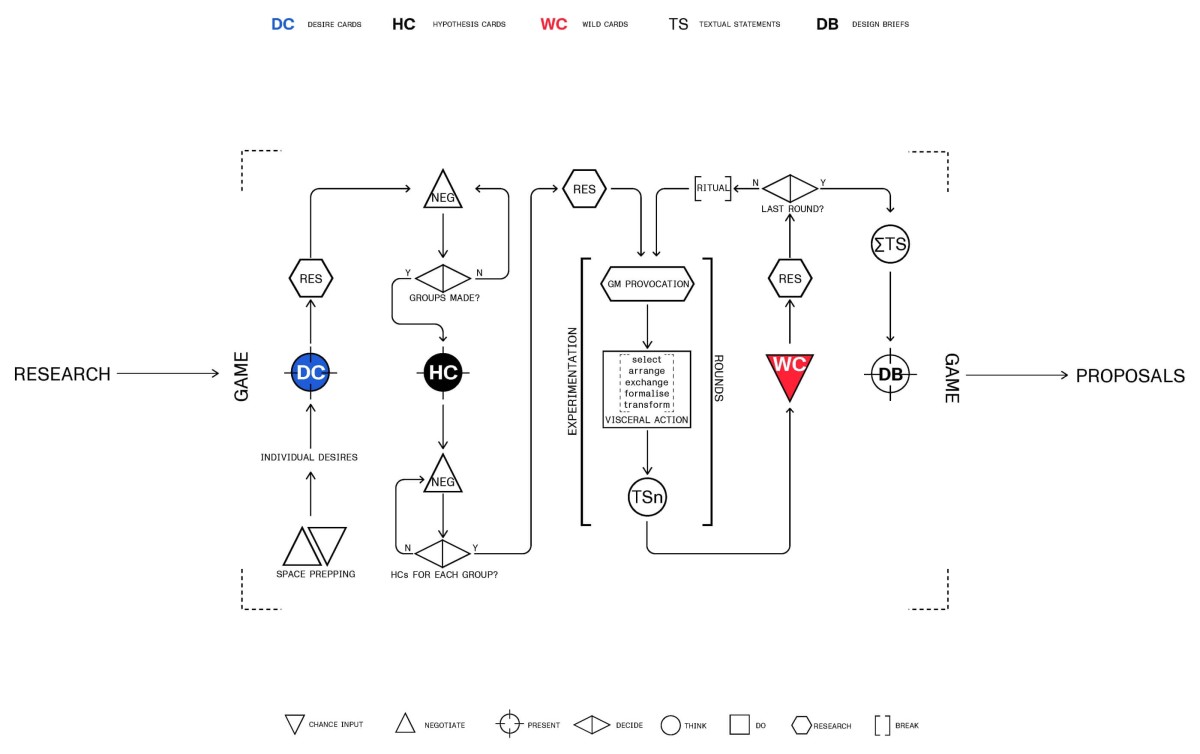

Situation Room methodology diagram, with a special focus on its game-like dynamics

Within the array of playful and game-based formats, situation rooms hold a special position. Situation rooms were first used for military purposes, and their format derives from the need to address emergencies through a multi-actor arrangement in a space single (which is enclosed, yet strongly connected to the outside) and in a limited (and usually critical) timeframe. What characterises a situation room is a heightened sense of heterotopia, achieved through the definition of an self-contained space where all information meets, an intense timeframe and chance (or unpredictable) inputs that force rapid decision-making, and a multivocal structure that nonetheless needs to provide a single response.

So, how can situation rooms be used to teach and test a different version of design? Here are a few key steps that describe a new methodology based on the situation room approach. The methodology is boldly structured in the following manner:

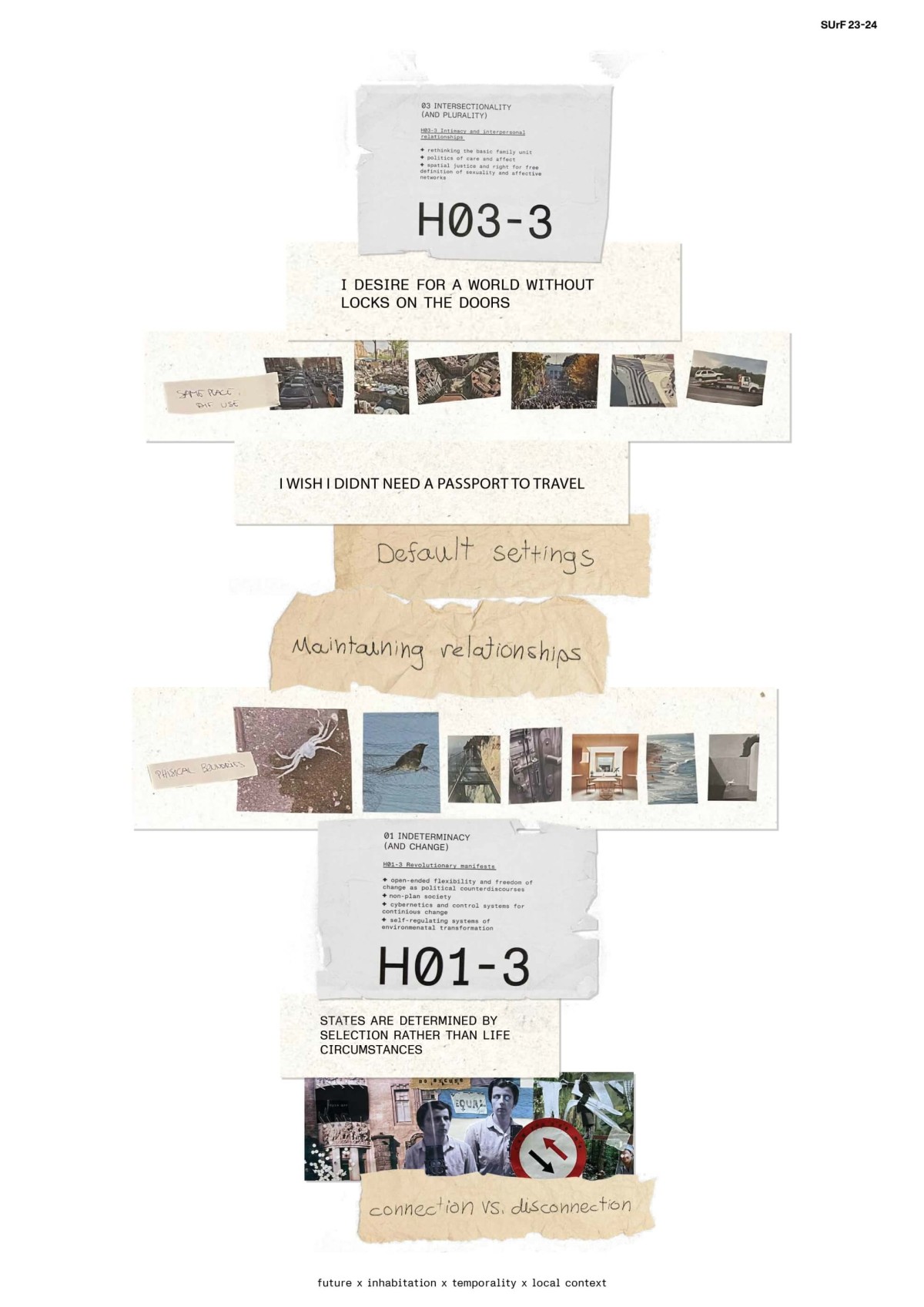

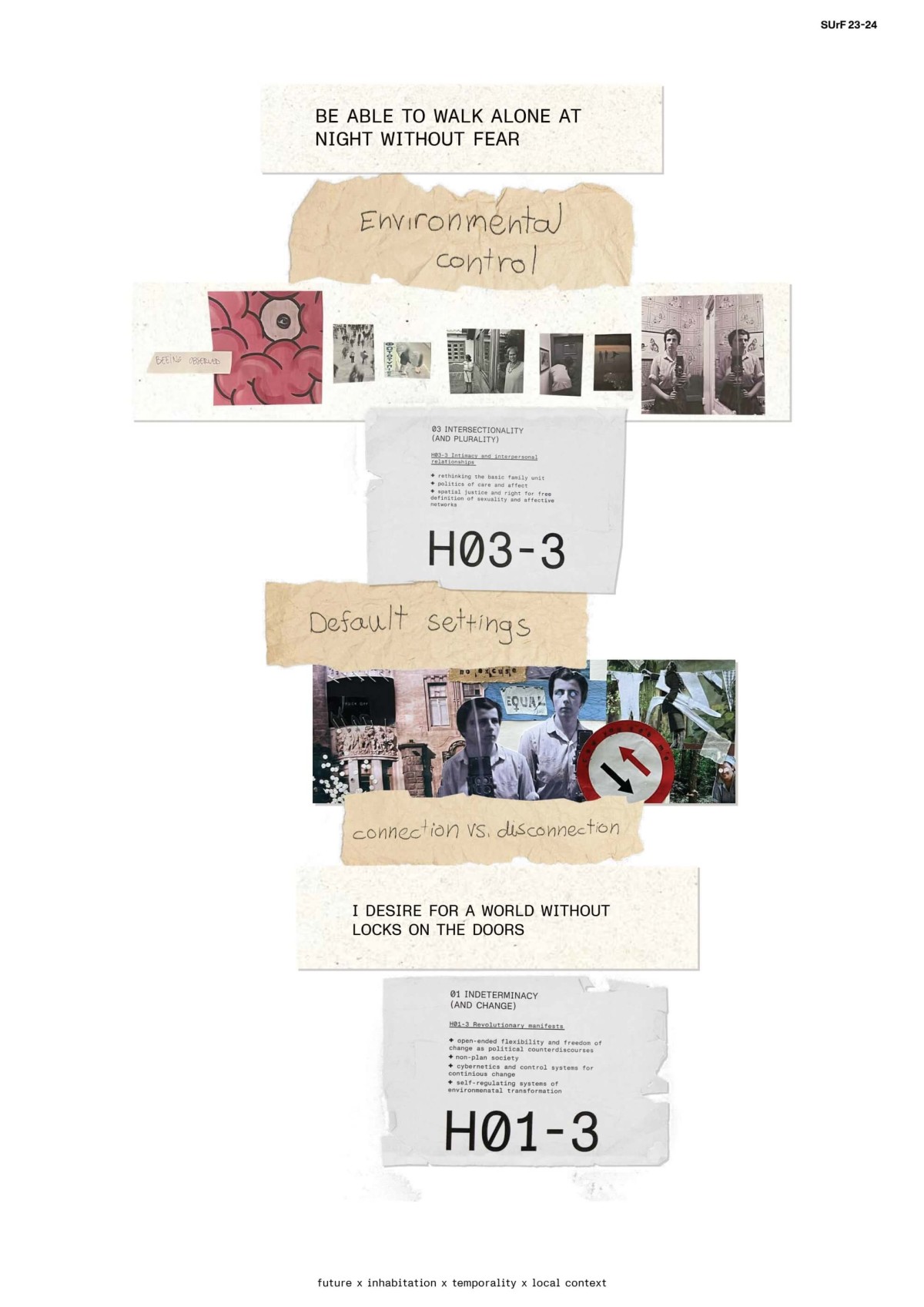

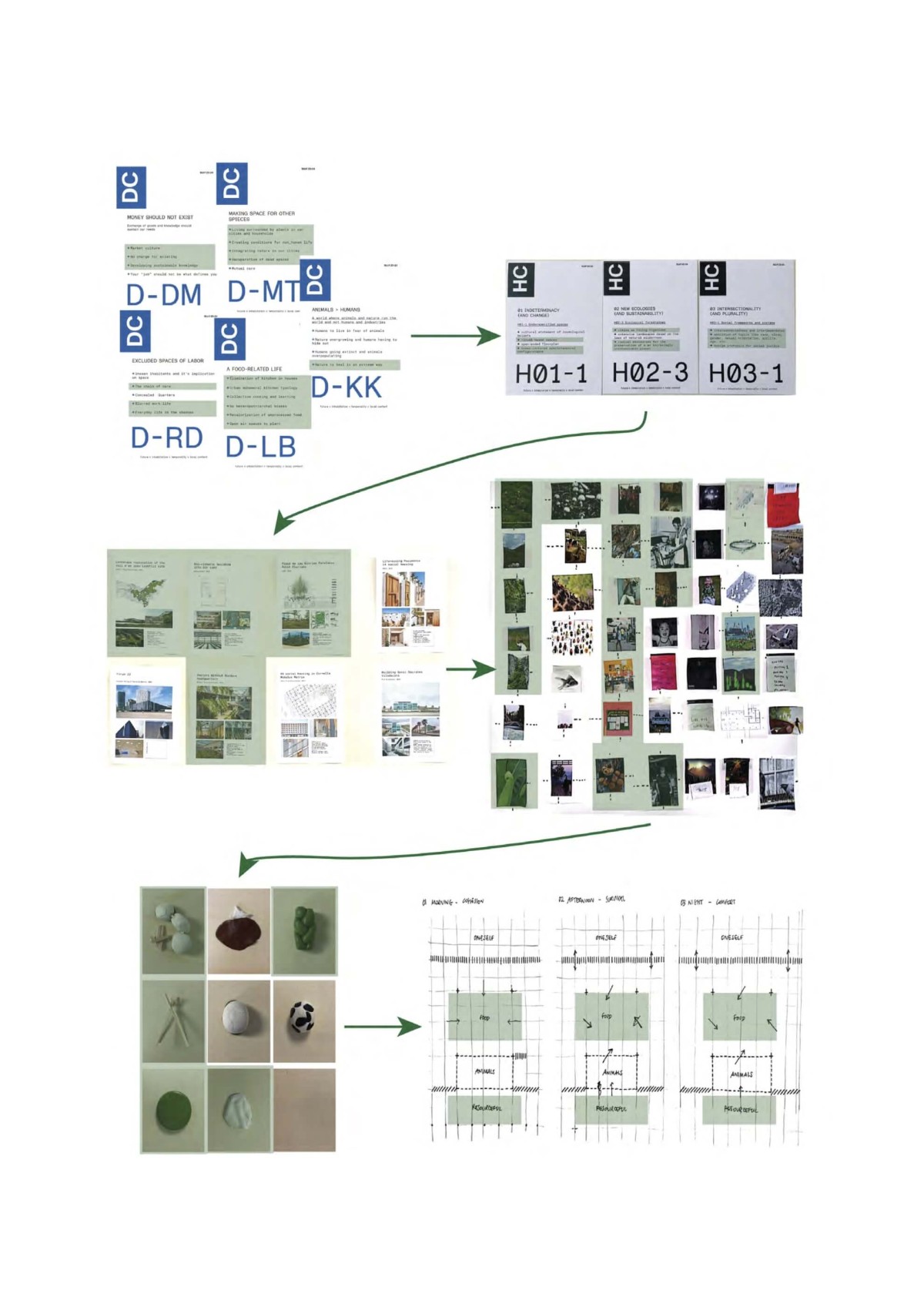

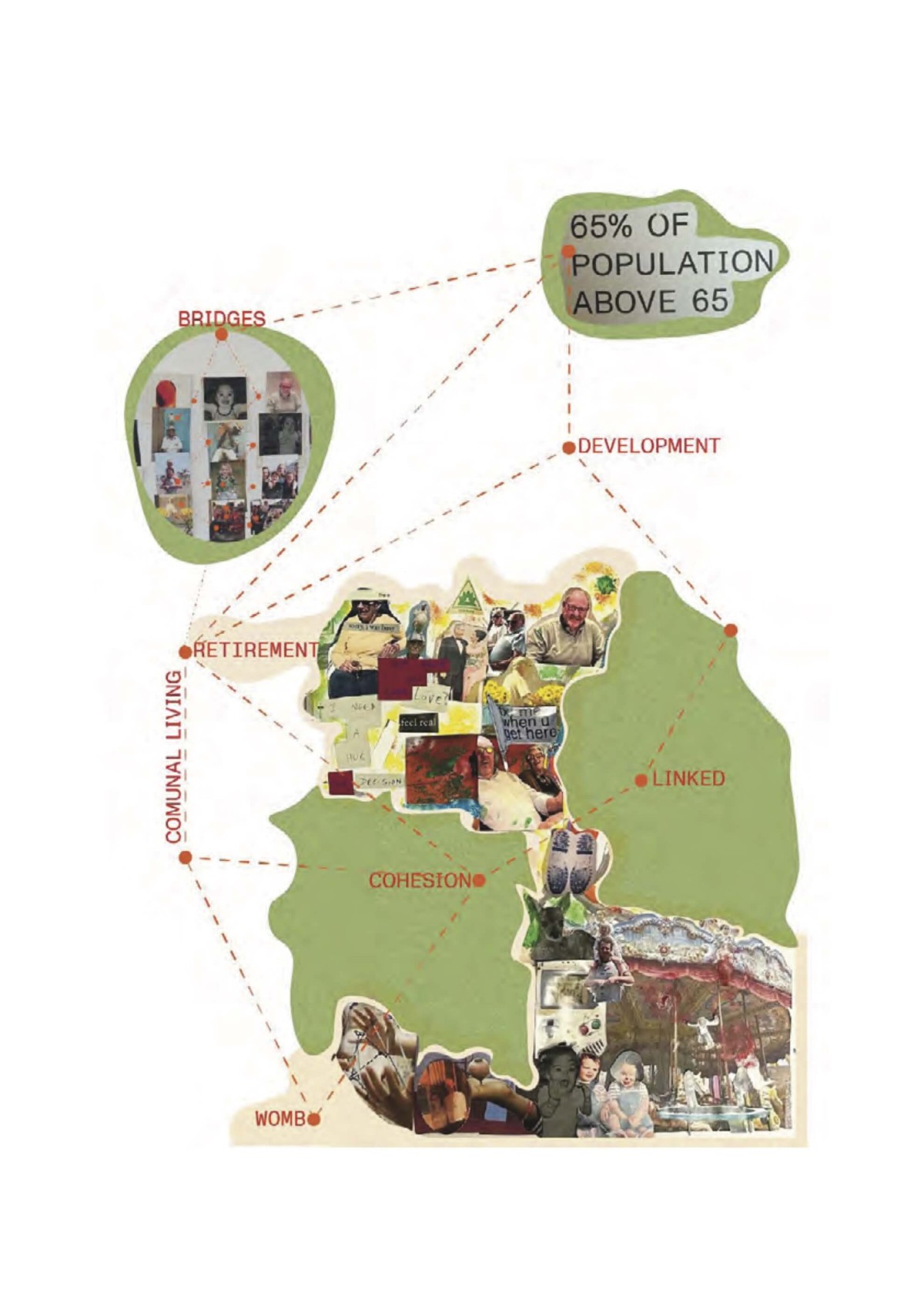

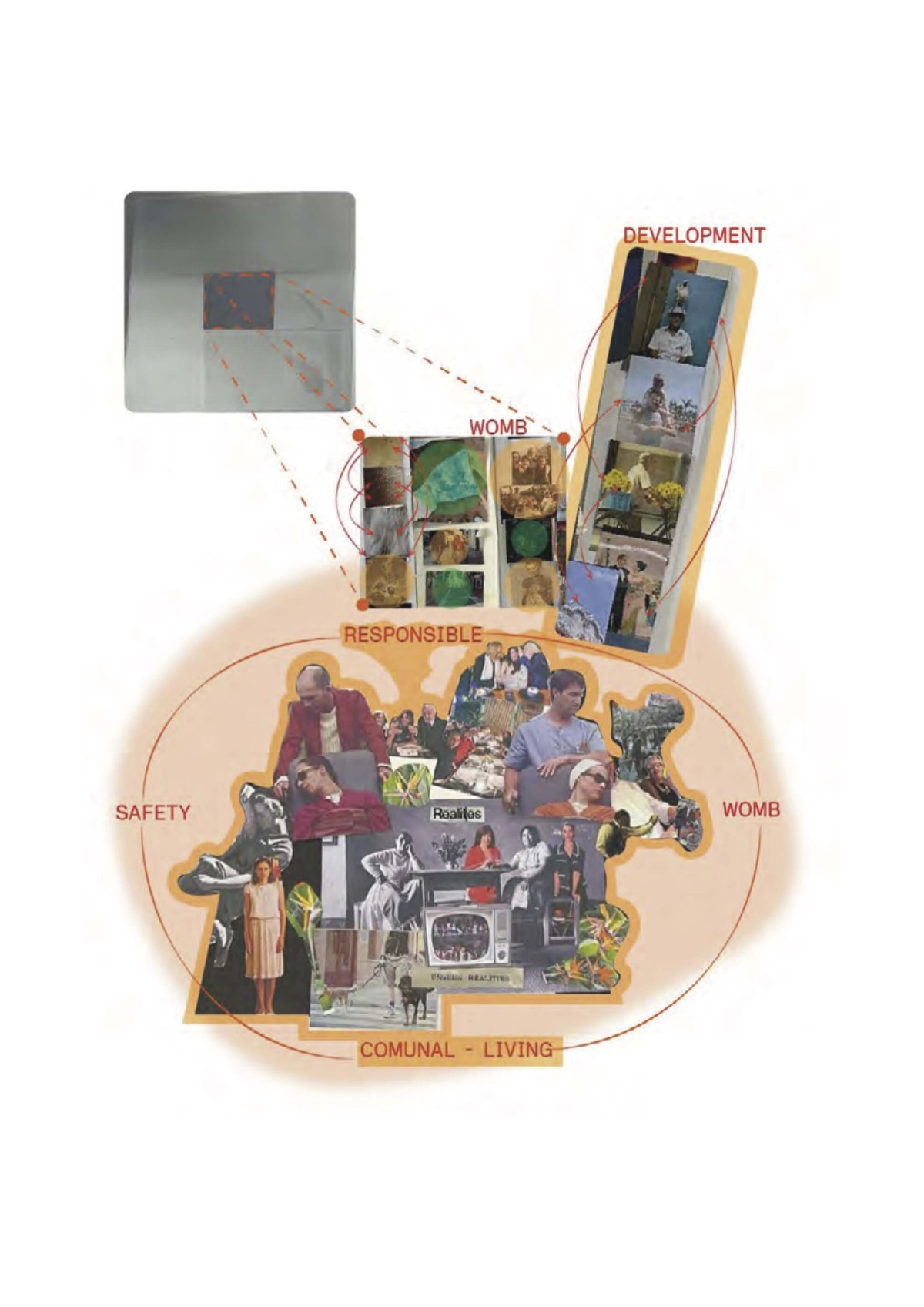

• Research to define the main challenges and hypotheses of the chosen topic, including the definition of the (physical, social and cultural) context of interest, and preparation of the research booklets and the cards needed to play the game.

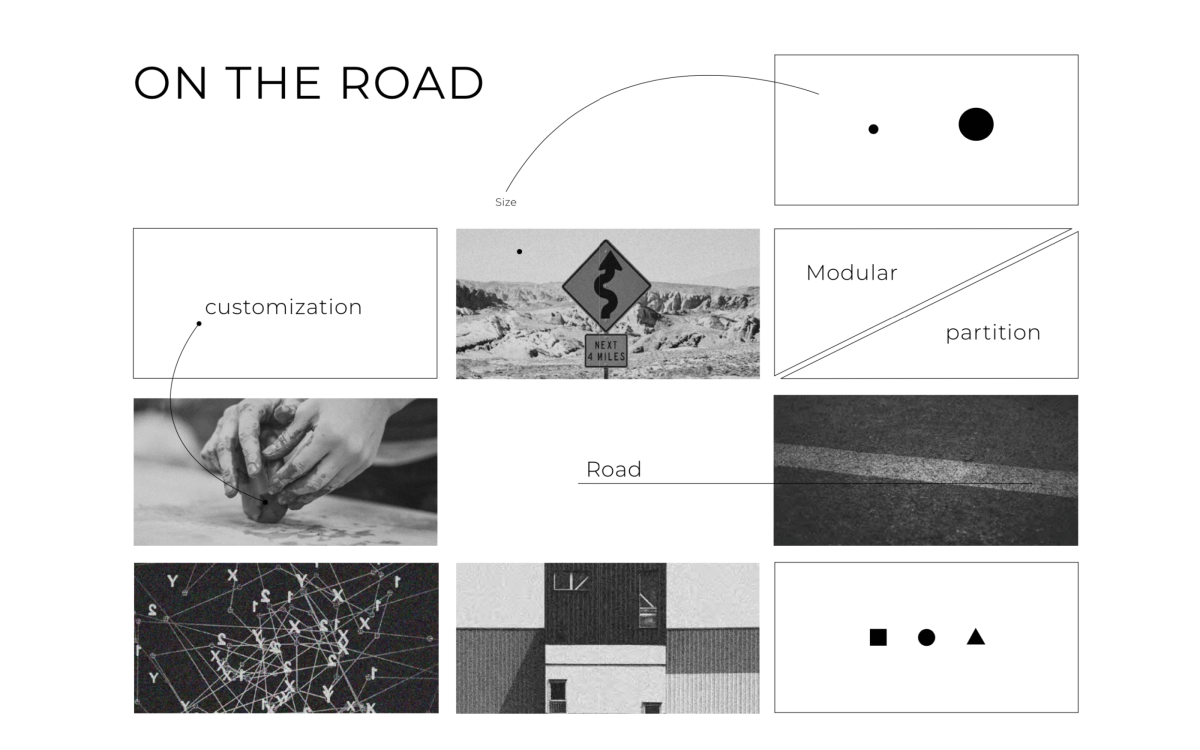

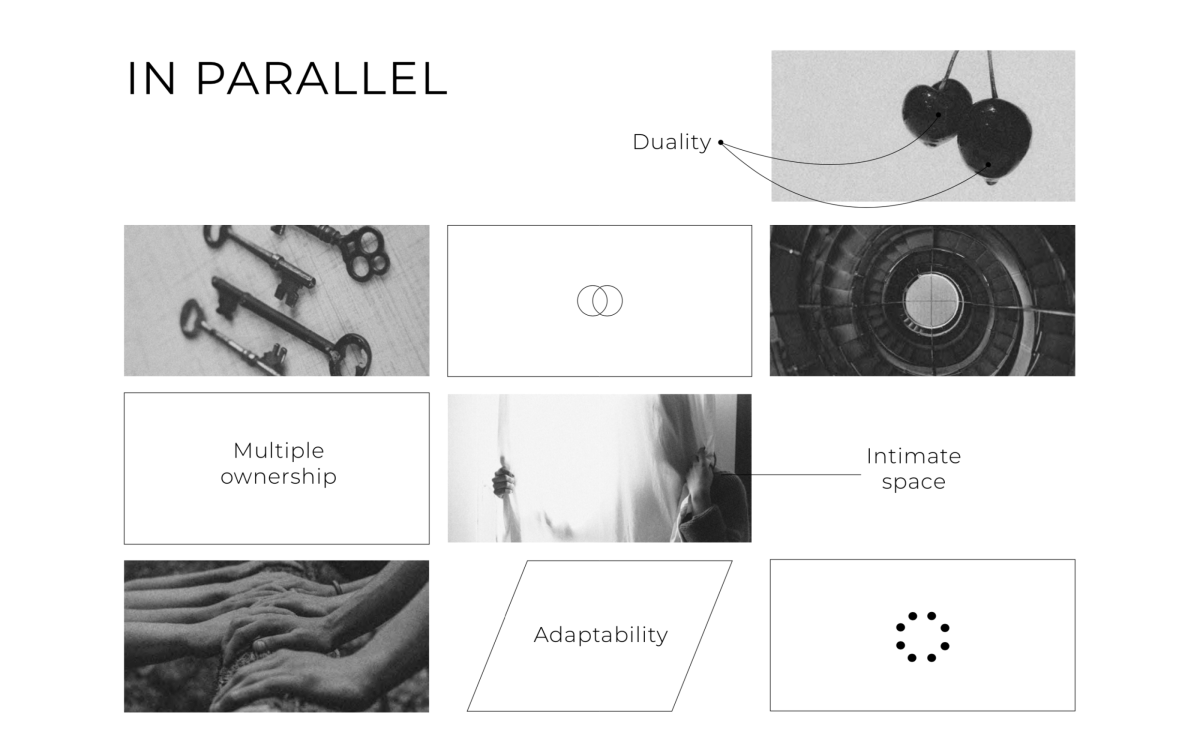

• Game-based practice in a situation room setting, fostering lateral thinking to explore novel ways of addressing design opportunities on the chosen topic and context, distilling them into design briefs with a potential high impact in triggering positive changes in the present.

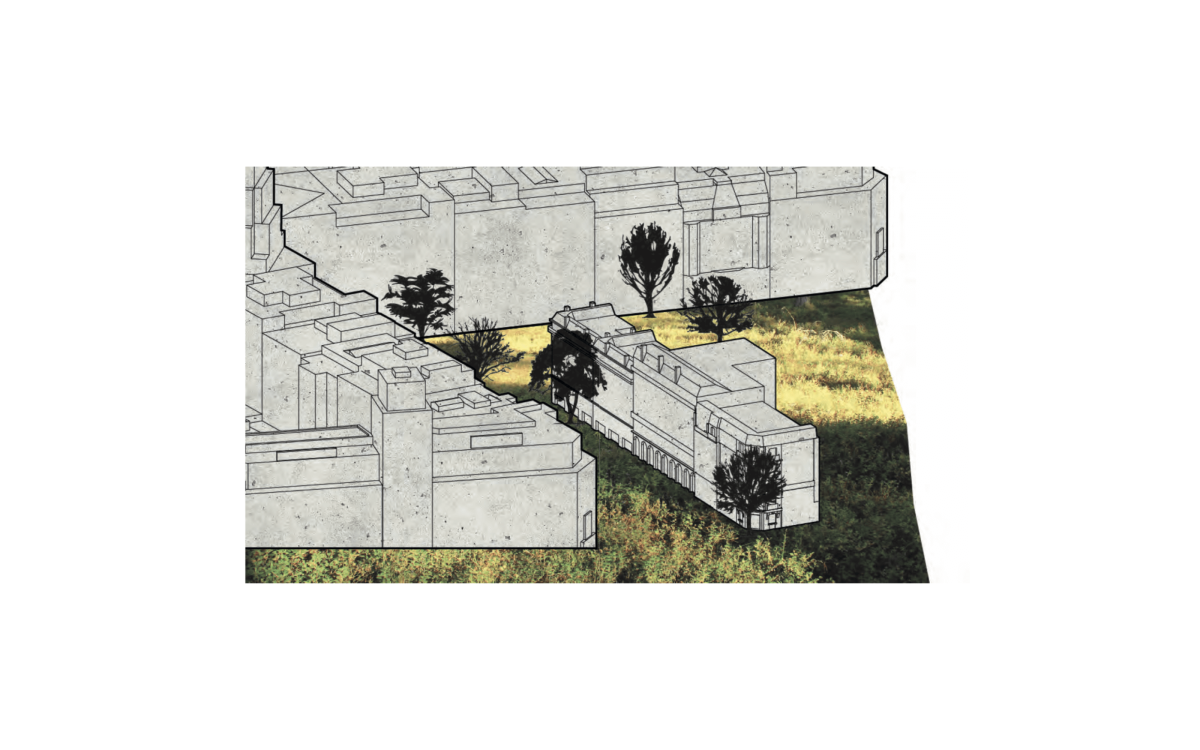

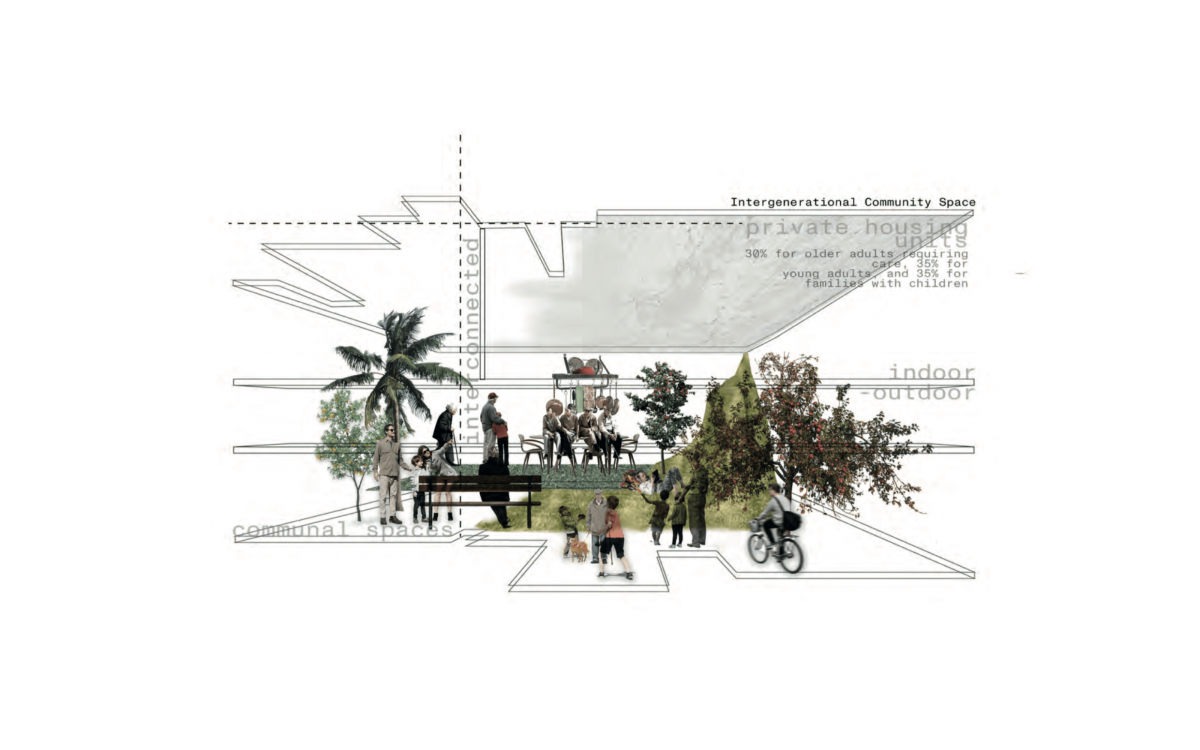

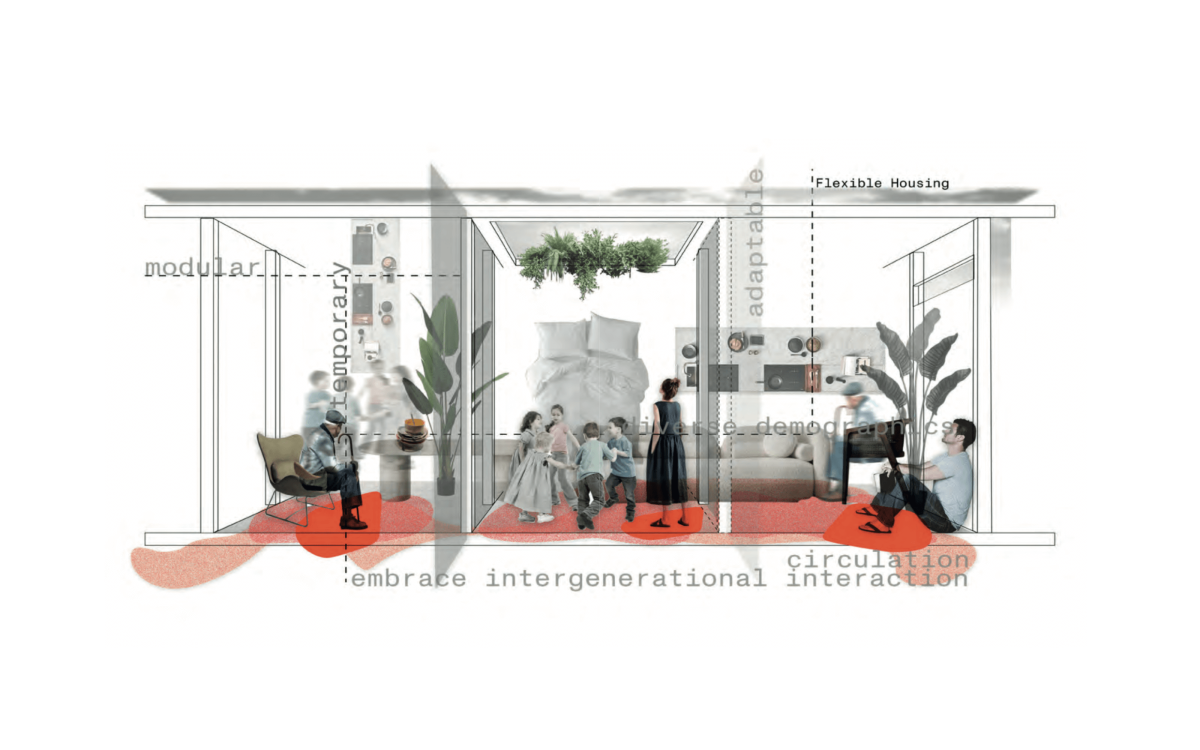

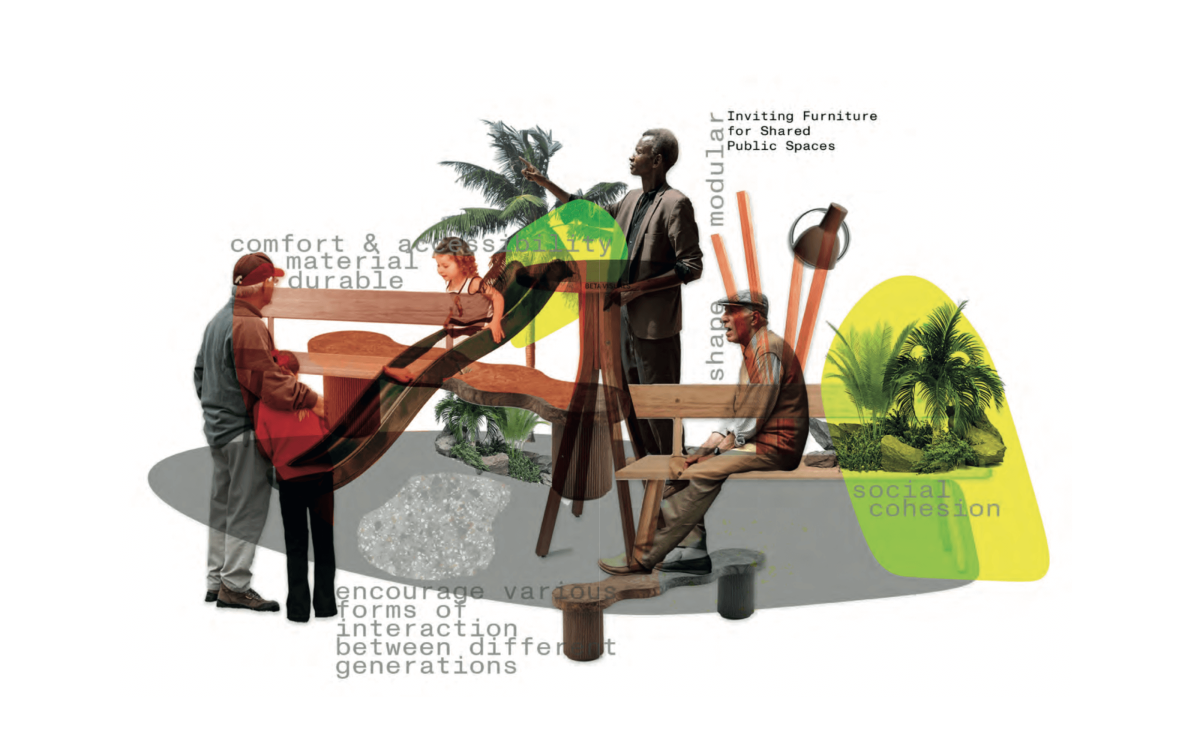

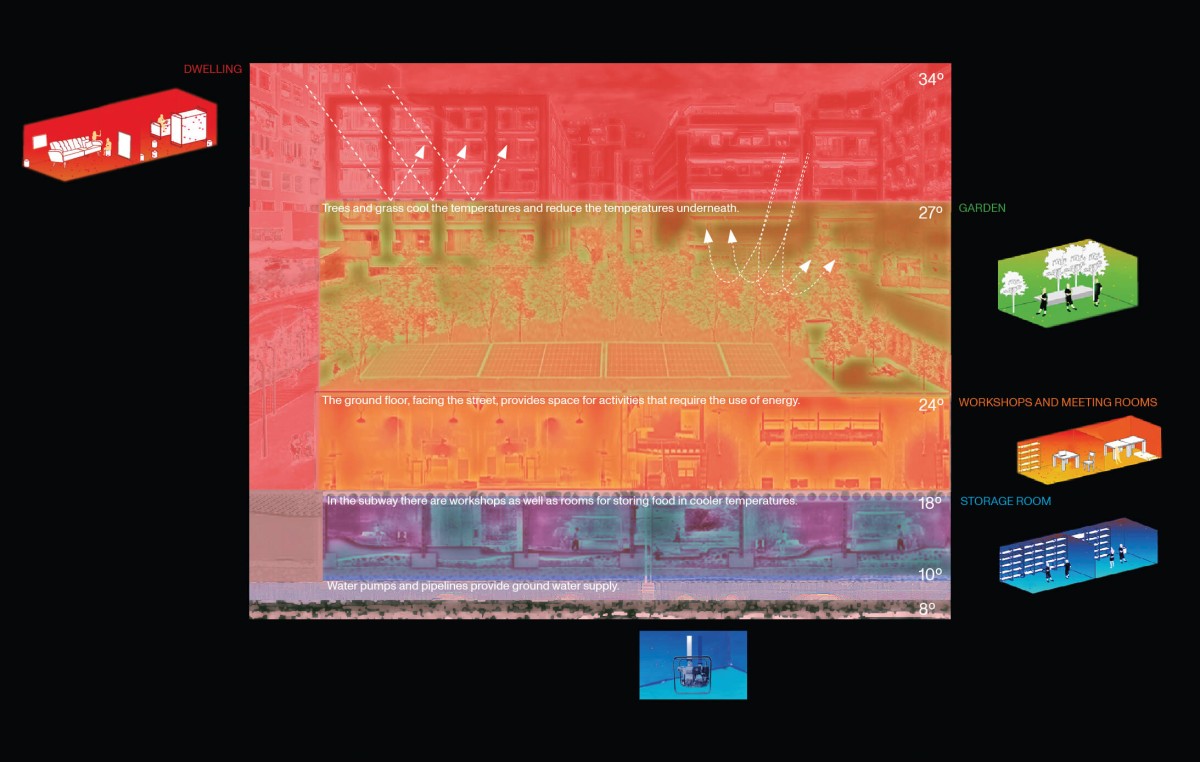

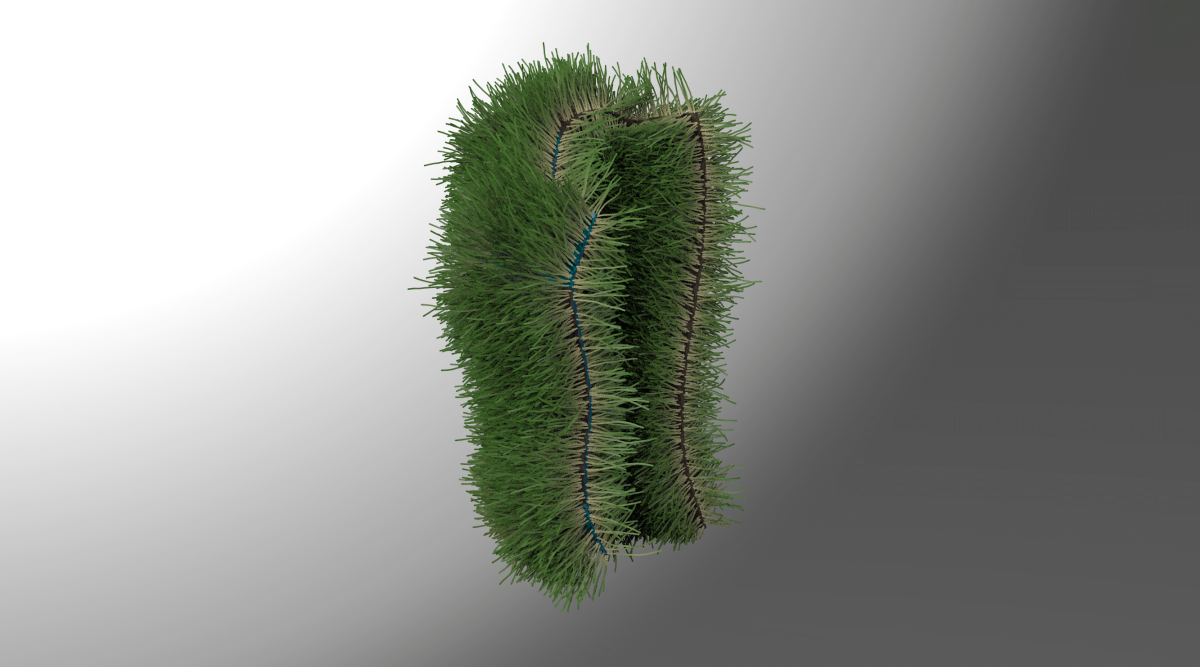

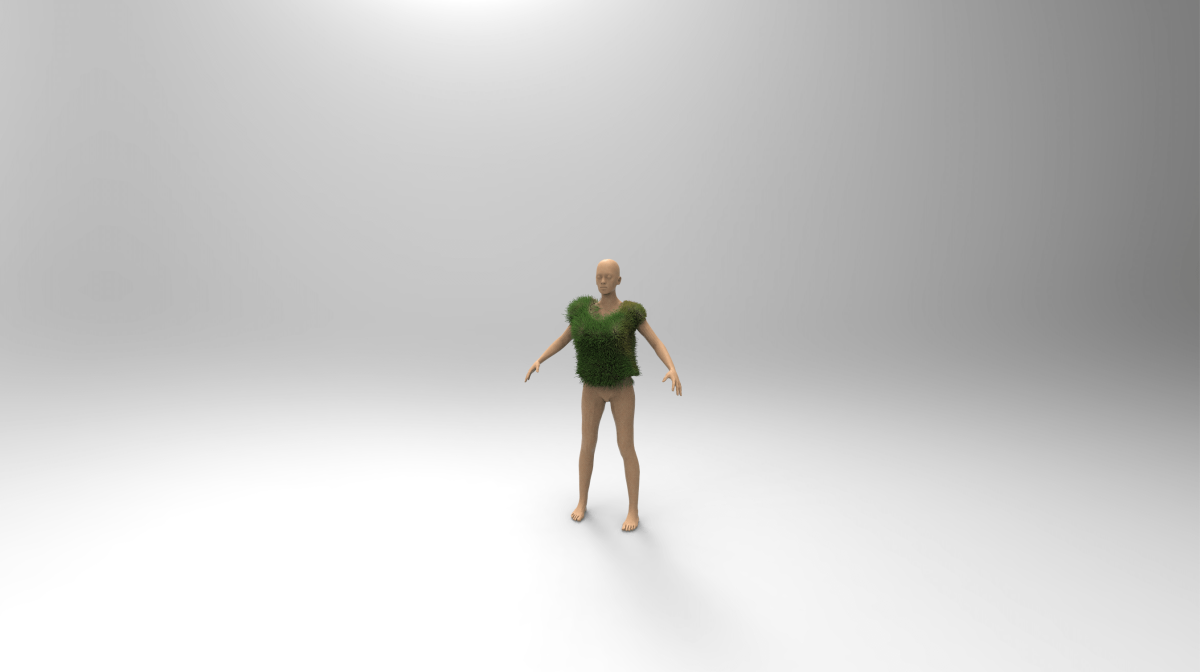

• Proposals responding to the design briefs generated in the previous phase. The main objective of the proposals is to test, visualise and evaluate future urban scenarios to prompt design challenges in the present.

This core methodology can be adapted to various topics of interest, matters of concern, skill sets, maturity levels of students, and timeframes, resulting in a rich array of possibilities. In summary, ELISAVA’s enactment of the situation room methodology in 2023–2024 addresses the aforementioned phases in the following manner:

• Research: researchers investigate the chosen topic (future of inhabitation) in relation to a specific aspect (temporality) and context (Catalonia). This research is summarised and formalised in booklets that are used as a starting point by master’s students in the game phase.

• Game: a) definition of the specific work space of the situation room, set apart from conventional space, time and rules; b) definition of the game inputs through three sets of cards (hypothesis, desire, and wild cards); c) definition of a strict game protocol based on multiformat iteration of the following sequence: individual desires, affinity groups, chance element (randomisation to obstruct linear thinking), negotiation process, exchange (fuzzy authorship), and collaborative assessment of (preliminary) results.

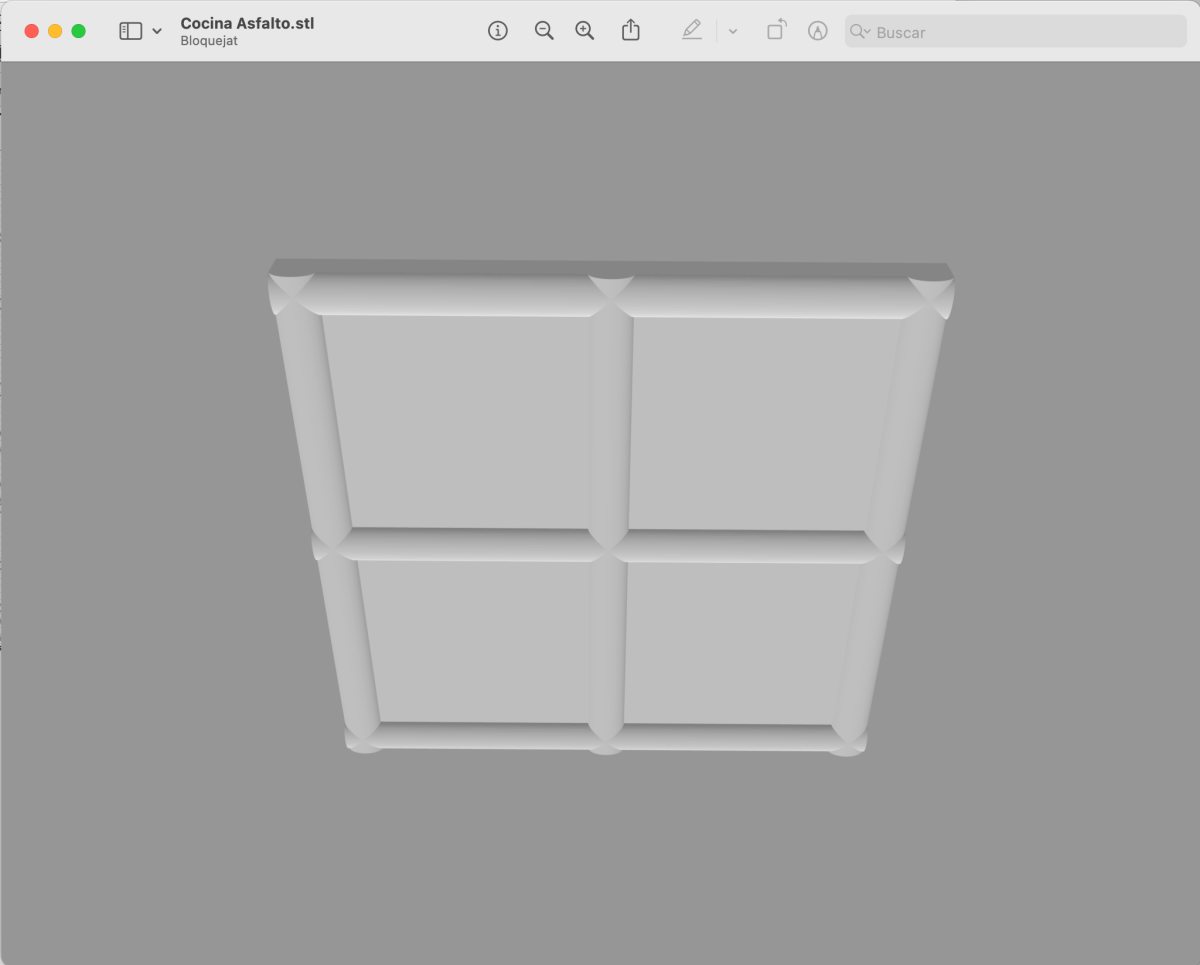

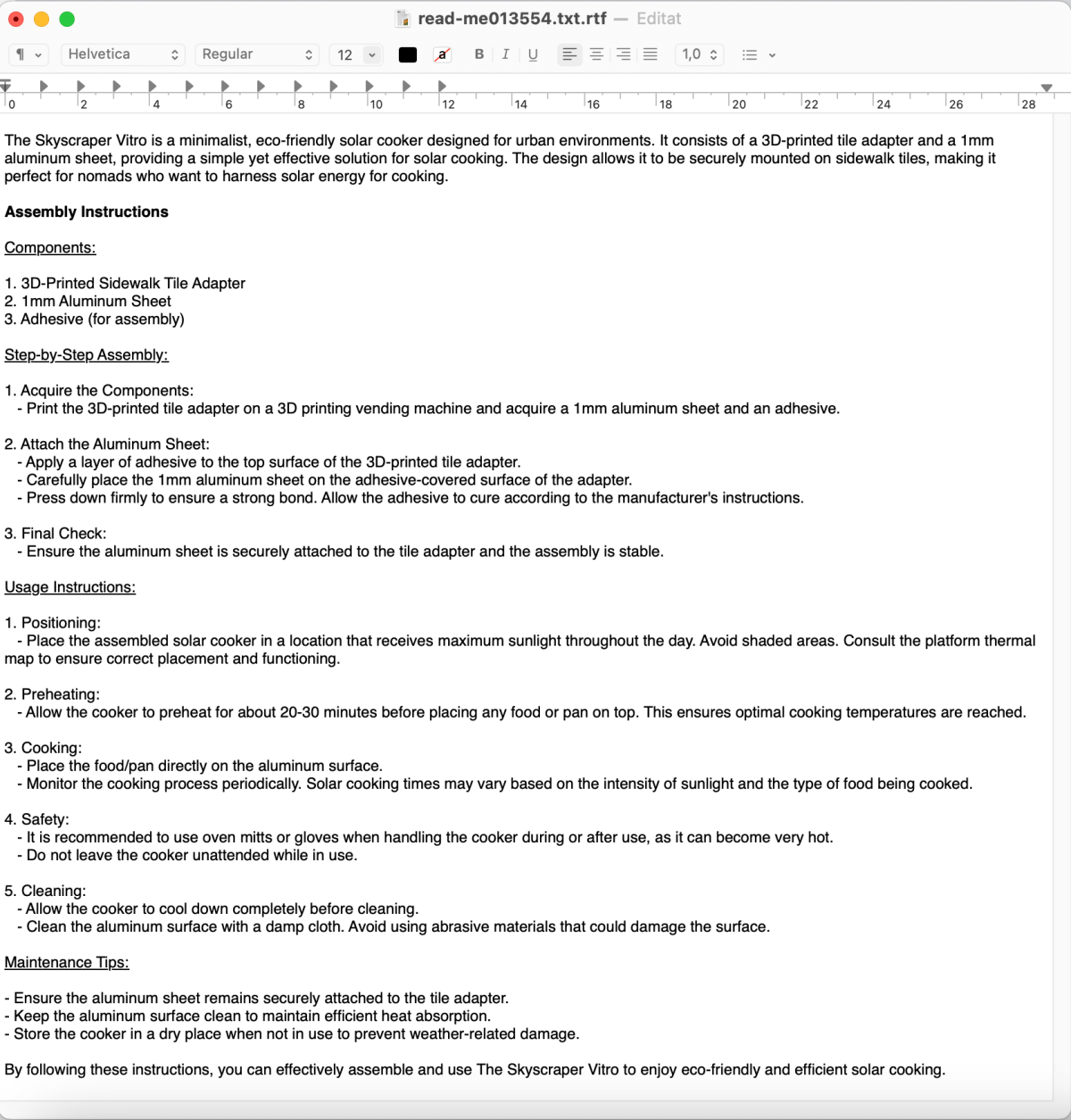

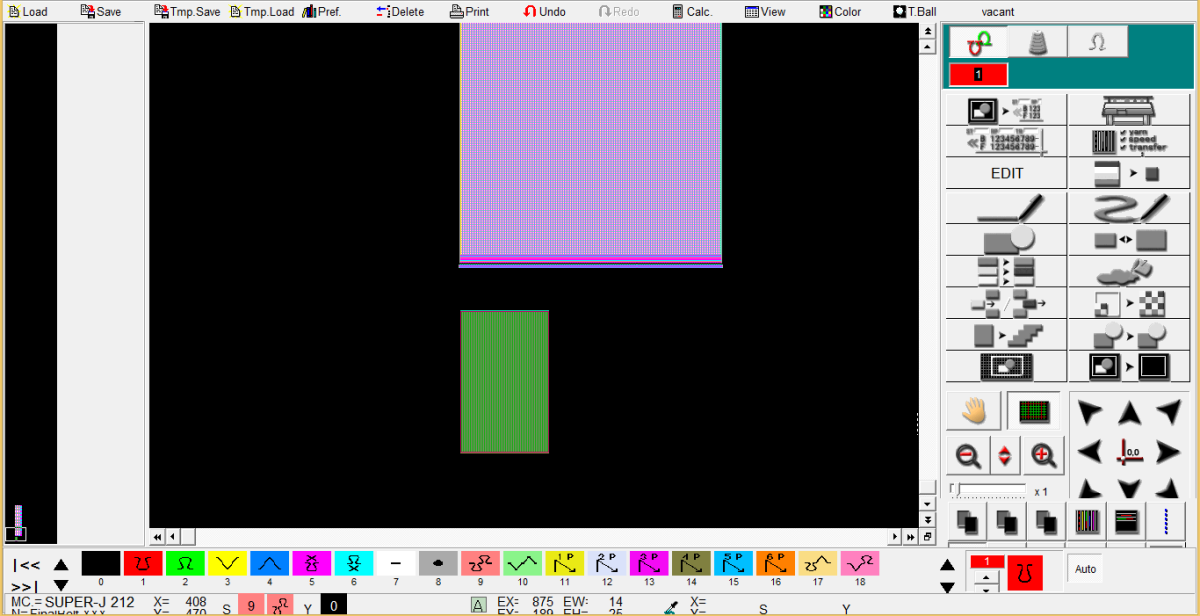

• Proposals: a different set of people, not involved in the game phase, receive the design briefs and respond to them individually using their specific design capacities, skill sets, design formats and personal interests, in order to test the validity of the methodology and its capacity to creatively imagine and rigorously explore speculative urban futures.

Perhaps the most vital use of game-based and playful practices in design, and their most valuable contribution to design education is the possibility to enrich creative thinking through constraints, authorial displacement and chance. Embracing chance and harnessing the constraints imposed by the game break down linear thinking and individualistic authorship modes, and in doing so they open creative paths that use immediacy and intuition in visceral ways, as well as rational-discursive thinking. Using situation rooms to engage with possible futures, and as tools to better understand the present, allows us to imagine and discuss desirable urban futures, and, most importantly, to transform them into specific design challenges that can be addressed by universities, research centres, professional practices and public administrations.