1In General

Philosopher Gilbert Simondon claimed that sensation is the grasping of a direction and not of an object. For French speakers this makes absolute sense (pun intended): in French, sense literally translates as direction. To make sense implies the capacity to both grasp where something is coming from and where it is going. It is in its directionality that sense becomes political: not in the strict understanding of the term but in approaching the political as any attempt to deal with complexity. Based on such (cosmo)politics, the philosopher Claire Colebrook claims that there is nothing more political than the opposition between reversibility and irreversibility. Time is fundamentally irreversible and all politics depends on this exact feature: while progressive politics acknowledges the irreversibility of time, conservative politics wishes to reverse time to what it once was.

However, in the current Anthropocenic condition, the irreversibility of time becomes palpable given that the effects of any action cannot be reversed – take, for example, climate change and its myriad consequences. Simply put, we cannot predict and correct, one can only intuit and speculate. As such, speculation becomes a sensitivity enhancer or an intuition booster. Through non-arbitrary ‘what-ifs’ one can begin to sense what ‘could’ come, and do so in a manner that can encompass and embrace the indeterminacy of a radically open and irreversible time. Being sensitive to time stands for being able to sense its indifference to any of our traditional temporal taxonomies – past, present, and future. Speculative time is a time in and of ongoing production, both in its actual dimension (what is being produced) and in its virtual dimension (what could have been produced). It is on this latter part that our speculative design pedagogies will concentrate. How do we sense (collectively and therefore technologically) the effects of our actions? How might we have been otherwise?

2In Particular

Within the scope of the Architectural Technicities MSc 2 Design Studio in the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, we will incorporate and develop an intensive workshop under the title Sensing-Intuiting-Imaging (SII). The workshop will bring together MSc students, PhD researchers, academic staff and invited guests who embark from different trajectories but focus on a single, shared interest: the production of speculative and intuitive problematisations. These speculations demand both: the formation of new sensibilities, as well as new forms that can express their potential. We shall call these forms ‘images’, but following a non-representational approach that does not equate them with shapes, outlines, or their tracings. On the contrary, we will open images to an untapped affective potential that provides not only an account of ‘what has been’ but can also invent ‘what is to come’.

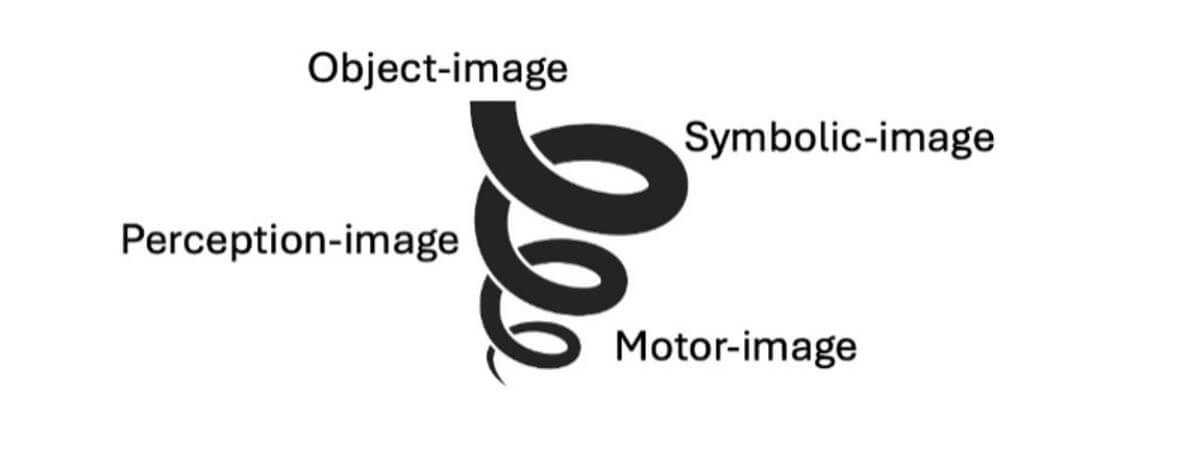

To do so we will follow Simondon and his ontology of images. Simondon refuses to relate images with human consciousness and intentionality alone, claiming instead that images are external to the thinking subject and are to be seen in connection with the action potential of (living) bodies. Understood as transducers between bodies (that can be interchangeably called subject or object), images establish vital linkages that allow organisms and their environment to form a joint system. This way, Simondon develops a pluralistic account of images in what he calls an imagistic cycle, consisting of four complementary phases with corresponding images:

• Motor-image:

For Simondon, the first images ‘are not conscious … since they precede perception (the reception of signals coming from the milieu), they are motor, linked to the most simple behaviors through which the living take possession of the milieu and proceed to the first identification of the (living or non-living) objects they encounter.’ Far from being confused with any representational fixation, primitive motor images have no other content than movement itself: they are autokinetic and non-finalised. It is this dimension of motricity and movement that constitutes the first phase of images, what we can call a motor-image. An example of a motor-image would be the act of drinking water.

• Perception-image:

Through and in movement, experience registers its own ‘being experienced’, leading to what Simondon identifies as the second phase of imagistic life, that of perception. The motor capacities exercised by an individual in its environment reveal affordances that in the act of being actualised formulate correspondences and associations between acts, environmental elements, and the individual itself. An example of a perception-image would be the river that affords the act of drinking water.

• Symbolic-image:

As a result of perceiving, images are organised and systematised, allowing the exercise of capacities we associate with consciousness. In other words, through the a praesenti of the activity of movement, the potential of a symbolic a priori (memory, the past), and a symbolic a posteriori (the future one longs for) is produced. An example of a symbolic-image would be the recollection or the anticipation of a river that affords the act of drinking water.

These three phases constitute the life of the image, which belongs to the relationship between the organism and the environment proper: movement, perception, and consciousness. It is at this exact point that Simondon introduces a crucial fourth phase related to invention:

• Object-image:

If the tensions between movement, perception, and the conscious systematisation of both cannot be resolved through bodily dispositions alone, then the need arises for a heterogeneous transducer. This transducer is the invented and technologically produced object-image. Object-images have the capacity to resolve disparate tensions between different orders of magnitude, effectively restoring the continuity of activity that has been interrupted. In doing so, object-images restore movement (albeit differentiated), and in doing so, they are bootstrapping the imagistic cycle once again (albeit differentiated). A transductive object-image thus alters motricity and leads to novel perceptions, leading to eventually differentiated symbolic systematisations of past and future values. An example of an object-image is the glass that is invented to automatise the act of drinking water by using our bare hands.

The four phases of the imagistic cycle highlight that images and imagination should not be conflated with visual representations or, even worse, with the act of an individual alone and its supposed psychic or intellectual capacities. What makes the ontology of images so appealing to Simondon is their transductive in-betweenness: both objective and subjective, abstract and specific, of the world and of the self. In simple terms, images do not belong to the individual and imagination is not a solipsistic act. Neither do they belong to an environment as an isolated container. Images, imaging and imagining are in and of the relation between organism and environment. They solidify, modify, and transduce their relation in ways that propel the individuation of both the organism and the environment precisely because they belong to neither. The SII cycle is thus not circular but spiral-shape:

Spiralling of the Simondonian Image Cycle, by the authors, 2024

3In Detail

The workshop takes place before the last part of the studio, in early June. It is preceded by a theoretical first part and a genealogical part that takes place immediately after the student field trip. In the theoretical first part, the students work individually to develop a problem that guides them for the rest of the studio and informs the setting up of student groups. Groups are formed based on problematic affinities, securing what we consider the first prerequisite in the production of any collective: sharing a common problem (that has not been imposed). The groups are assigned different urban areas or conditions that correspond to their common problem. The whole studio then goes on a field trip where on-site research, interviews and seminars take place. Upon their return, the students attempt to identify the singular points and moments that are open to intuitive speculations by developing a thorough genealogical approach. Upon the conclusion of this genealogical part, the second part of the studio in the form of SII begins.

SII is spread over two weeks and consists of five intense workshop days: the first day serves as an introduction to Simondon’s imagistic cycle, where a series of lectures qualify and explain its four phases in detail. Each of the four remaining workshop days focuses on a specific image: from motor-image to perception-image to symbolic-image, concluding with the object-image. Each of these days will be divided into two parts: the morning is dedicated to production (following detailed instructions offered by the workshop tutors) and the afternoon is reserved for the student groups to present their work. In addition, each day is expected to build upon the work of the previous days, following the individuation of an imagistic cycle. The workshop concludes with the presentation of object-images by the student groups. All student work, throughout the workshop, in all different image phases and in all different formats (sketches, diagrams, videos, choreographies, sonic elements and so on) is presented and developed on a single A1-size sheet.

Below is a detailed overview of the workshop schedule per day.

4Day 1. Introduction on Simondon’s imagistic cycle

Simondon’s imagistic cycle is thoroughly introduced through lectures and discussions. The four phases of images are laid out, with a discussion of their philosophical and theoretical background, their broader implications, their potential and their radical differences from traditional approaches, and their relation to architecture thinking and doing.

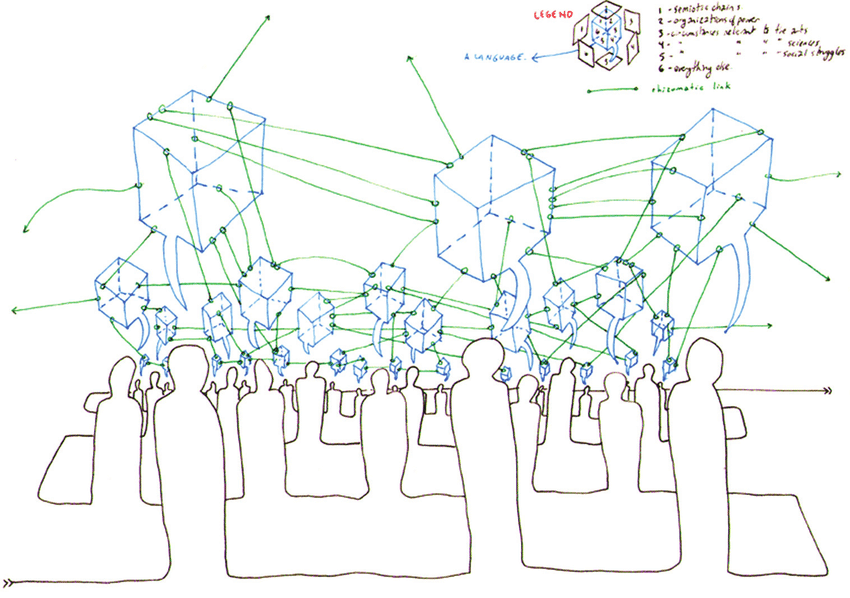

5Day 2. Motor-images and flows

We examine motor-images as the primary movement of flows. The students speculate on which kinds of flows are involved in both their theoretical problem and in the urban conditions of their assigned area. The output of this day is a diagram expressing the movement of the relevant group-specific flow(s). The diagram can be hand drawn, digital or a combination of both, but in any case, non-representational.

Diagrams for Deleuze and Guattari's A Thousand Plateaus by Marc Ngui, 2012

6Day 3. Perception-images and the context of flows

We examine perception-images as the registering of flows and their assignment to a specific place and time. The students speculate on where and when the flows are registered in their area. The output of this day is a map that points out and captures the spatiotemporal specificities of flows. The map has no scale constraints and does not necessarily need to be a traditional urban map; the façade or the section of a building is as good a map as any.

Map of Naples, Richter, 1886

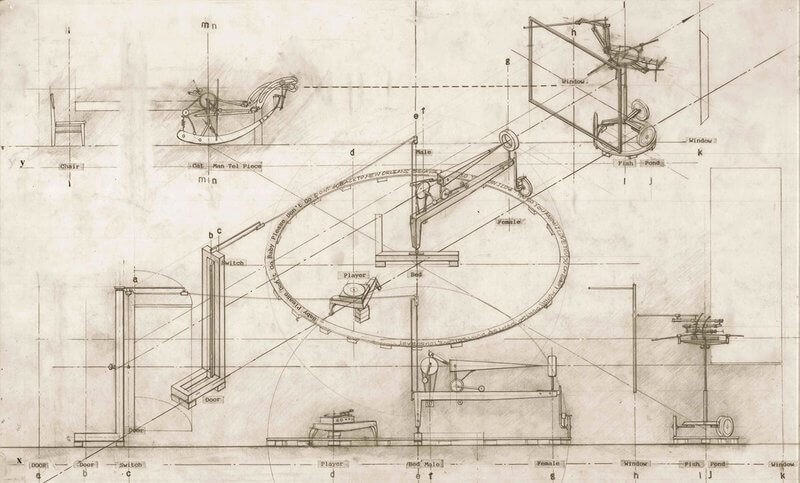

7Day 4. Symbolic-images and the cognition of flows

We examine symbolic-images as the resingularisation of flows. The students speculate on how flows are taken away from their specific context, expressed in their most singular aspects and are eventually opened to a potential anywhere and a potential anyone. The output of this day is an encyclopaedic notational drawing that expresses what is singular in a flow regardless of context.

Bed Machine by Shin Egashira, 1992

8Day 5. Object-images and the invention of flows

We examine object-images as flow inventors. The students speculate on how novel flows are invented when the captured, contextualised and eventually resingularised flows transduce from one domain to another. To achieve this, the groups exchange their problems among themselves as expressed in their symbolic-images. The output of this day is fundamentally open and not to be determined in advance.