Simply stated, counterfactual histories use the technique of modifying the outcome of a historical event and then extrapolating a new version of history leading to an alternative present. In literature, imaginaries based on a poignant counterfactual history can offer thought-provoking insights and perspectives on contemporary life.

Counterfactuals have a long and diverse history across many cultures. They often turn on political or military events, such as a different election outcome (Franklin Roosevelt being defeated in 1940 in Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America) or the outcome of a war (the victory of the Axis Powers in Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle). Sometimes history is ‘flipped’ in a prolonged ‘what if’ thought experiment, as in Malorie Blackman’s novel series Noughts and Crosses (2001– 2021), in which Europe has been colonised by Africa. They may also serve a pedagogical purpose by revealing the path of a life unloved or unlived, as in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol (1853) and Frank Capra’s film It’s a Wonderful Life (1946).

Historians especially tend to focus on military ‘decision points’ – a battle lost instead of won, a war avoided instead of launched – at which events could have taken another path (Bernstein 2000). Alternatively, counterfactuals imagine the absence of powerful individuals from specific events to speculate on how things might have played out differently. (In the context of design, for example, this might be something like: what if Steve Jobs never visited Xerox Parc in 1979?). Alternative presents, developed from poignant counterfactual events, can offer thought-provoking insights and perspectives on contemporary life, as well as an examination of the past. Since history is often written by the victors, it tends to “crush the unfulfilled potential of the past”, as Walter Benjamin so aptly put it. By giving a voice to the “losers” of history, counterfactual histories allow for a reversal of perspectives’ (Deluermoz and Singaravélou 2021).

In this way the approach can open up new possibilities for the future beyond the narrow path of iterative design and the blinkered view of ‘capitalist realism’ (Fisher 2009) to assist in the envisioning and building of alternative futures. This approach is not limited to the future, either: a rich parallel history of what-if counterfactuals exists in tandem with future-oriented speculations. The anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1989) famously defined the term ‘faction’ as ‘imaginative writing about real people in real places at real times’; here instead we are engaging in unreal or parallel or alternative times.

This then is the basic premise, and promise, of counterfactual histories especially as applied to design pedagogy: to break out of constraining lineages and narrow pathways through the imagining of alternative narratives and the application of alternative values. Such speculative proposals ‘question existing paradigms through the use of different ideologies to those currently directing product development. These are speculations on how things could be, had different choices been made in previous times’ (Auger, 2012).

At the top left is an emerging technology in the context of laboratory research – the higher the line the more naïve the technology. The potential of the technology can be extrapolated (through theories of domestication) to inform speculative futures (extrapolations of the product lineage). For the SUrF project we focus on the counterfactual approach – stepping outside the lineage at some relevant point in the past to develop a different version of the present.

Counterfactuals provide an almost surreptitious method of combining design theory with practice. Through a rigorous analysis of history as it relates to a specific subject, the designer can identify the key elements that are problematic when viewed through a contemporary lens of practice. The approach can expose dominant structures of power and the influence these have on design culture and metrics: for example, the pervasive influence of legacy systems and the attention economy, and how they limit the imagination and constrain possibility.

So, how to teach a different version of design? Here are a few key steps that describe a new methodology based on the counterfactual approach. The design brief is structured in the following manner:

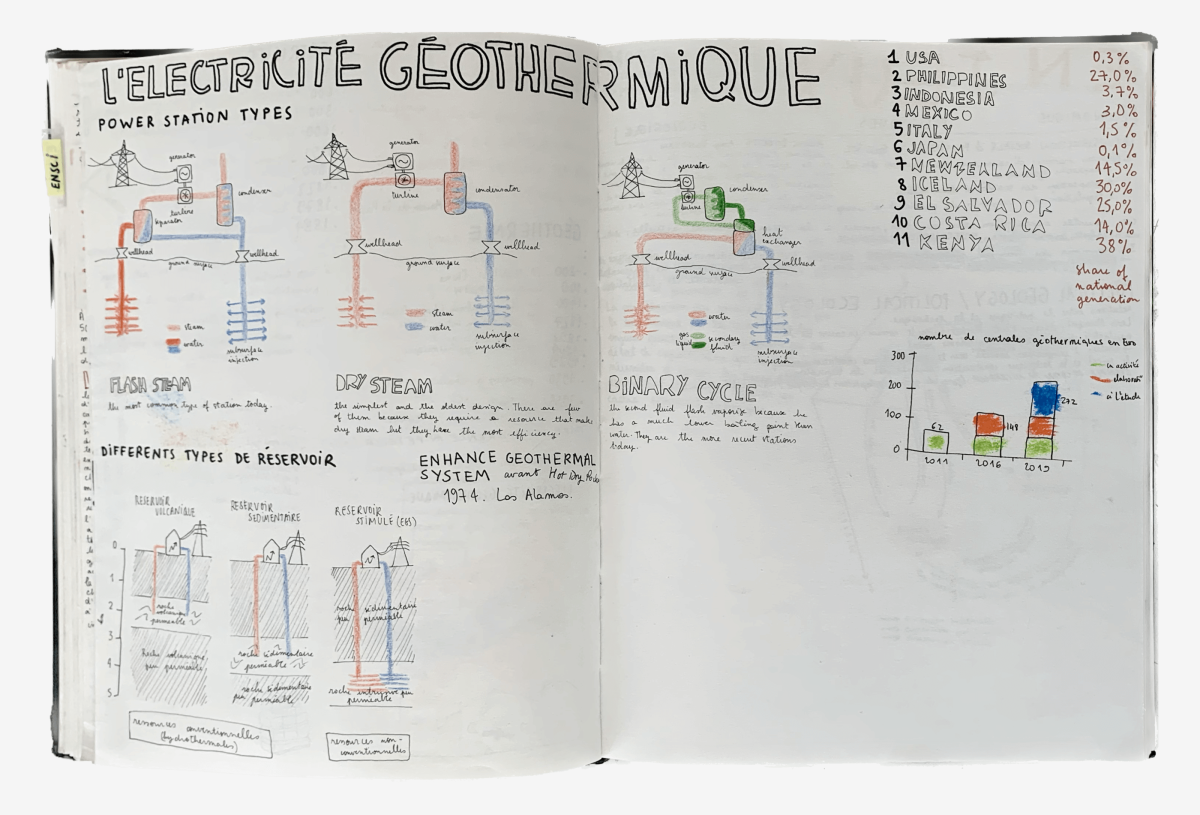

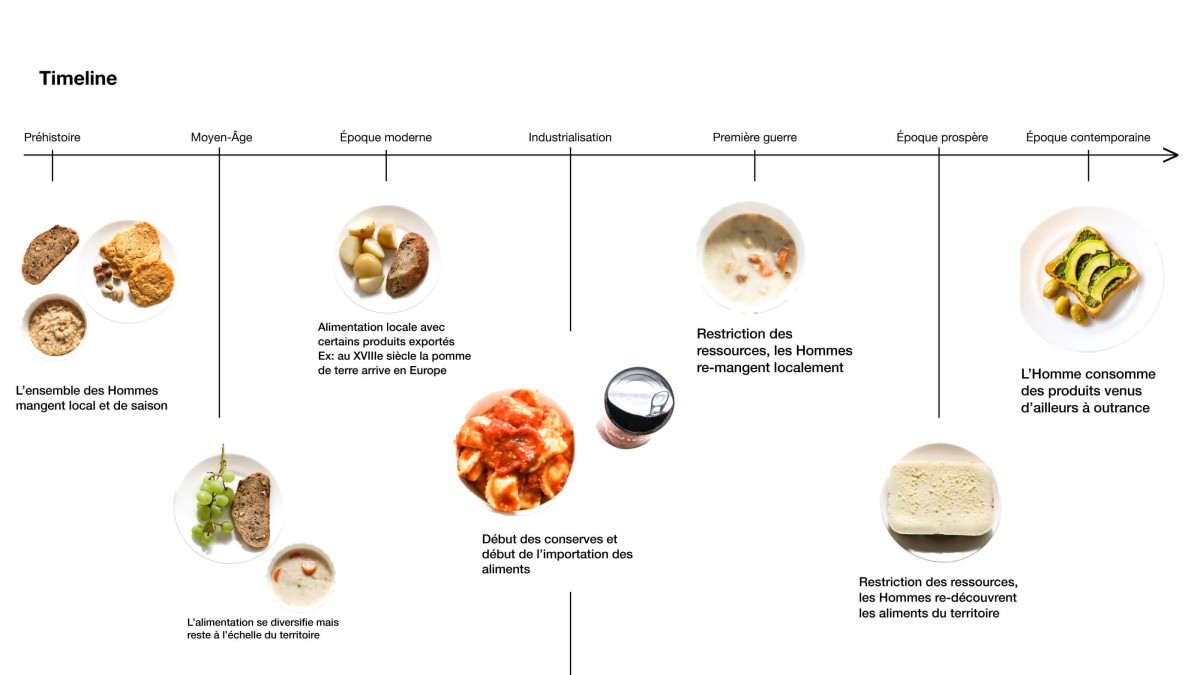

• Definition of the theme or subject followed by a broad mapping of its related systems. These can then be examined historically to create a detailed and diverse timeline of the subject – the key moments that led to the current world (for example, a political decision, an invention, a celebrity endorsement, a natural disaster). These can then be analysed critically to identify the event(s) that contributed to the problematic contemporary situation.

• The creation of a counterfactual timeline based on a different outcome of an event identified on the real timeline. One of the key benefits of this approach is the necessity to understand complex histories and how they inform, influence or constrain design practice. Experiment with different themes and examine the potential consequences. Remember that the further back in time, the more divergent the alternative present will be, and therefore more fictional and complicated to manage – as Ray Bradbury’s classic tale ‘A Sound of Thunder’ illustrates (Bradbury 2005).

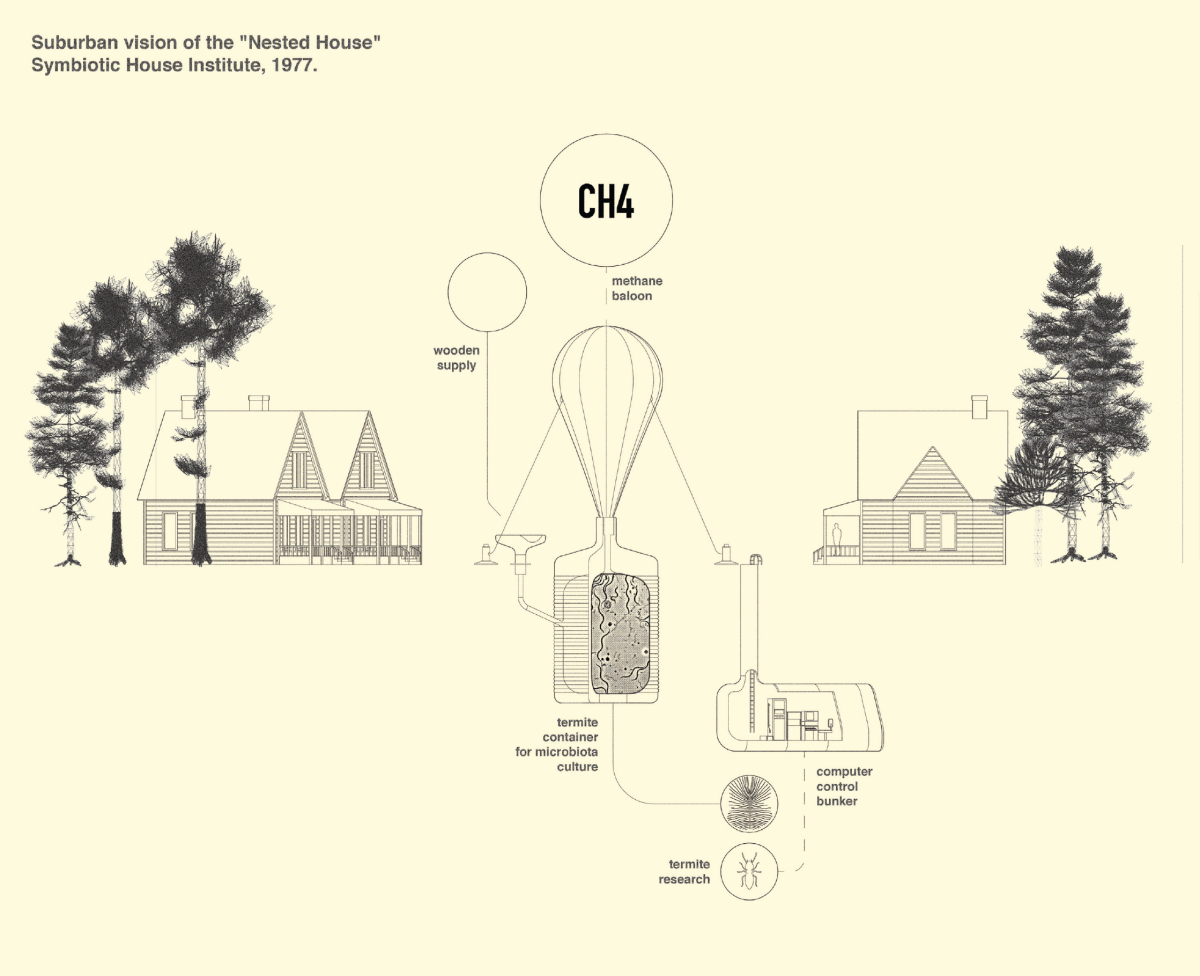

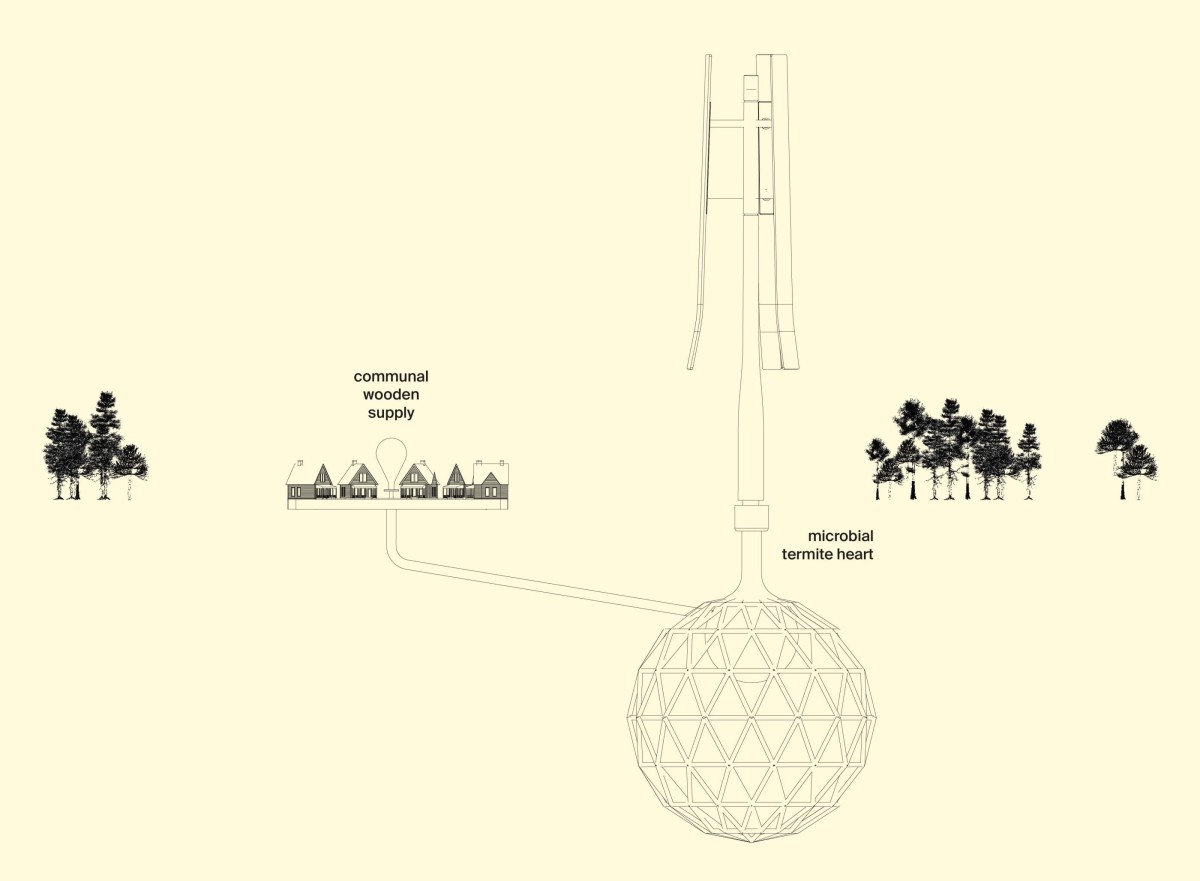

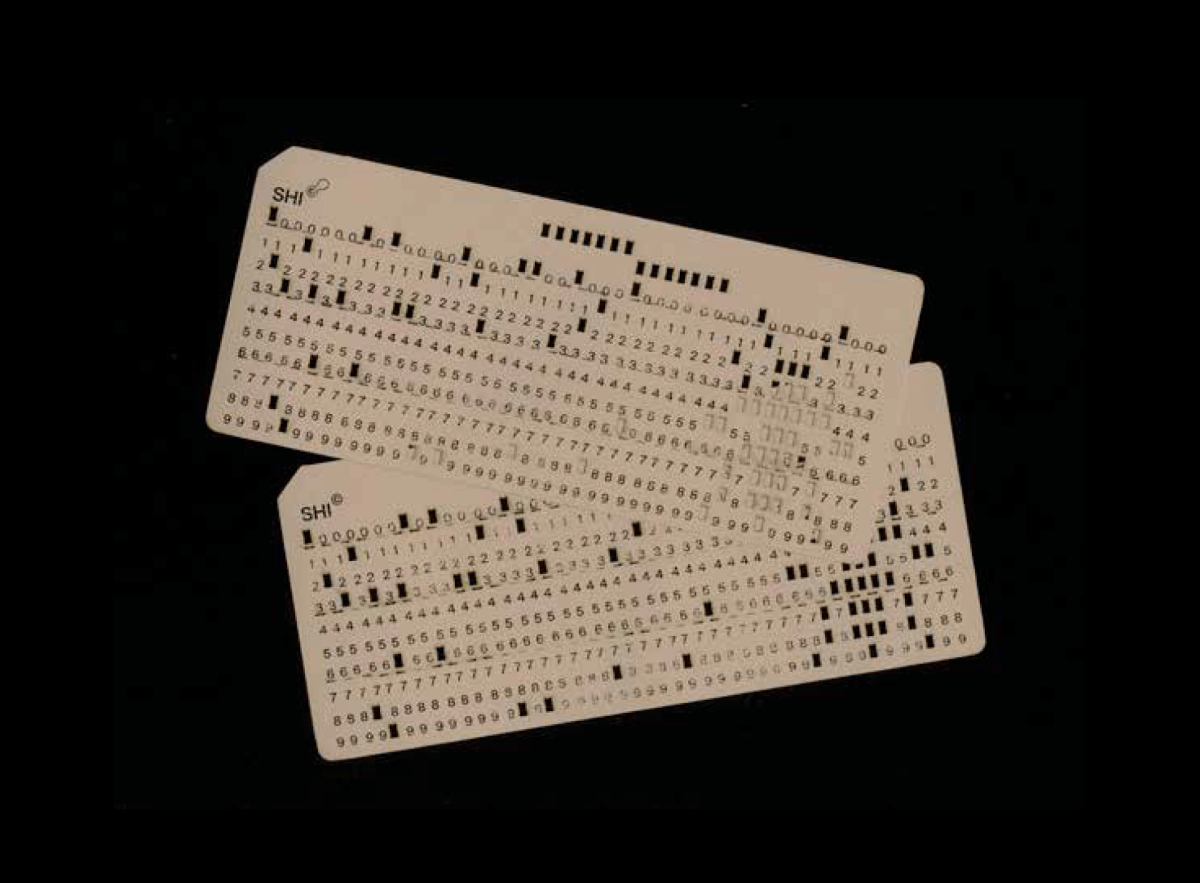

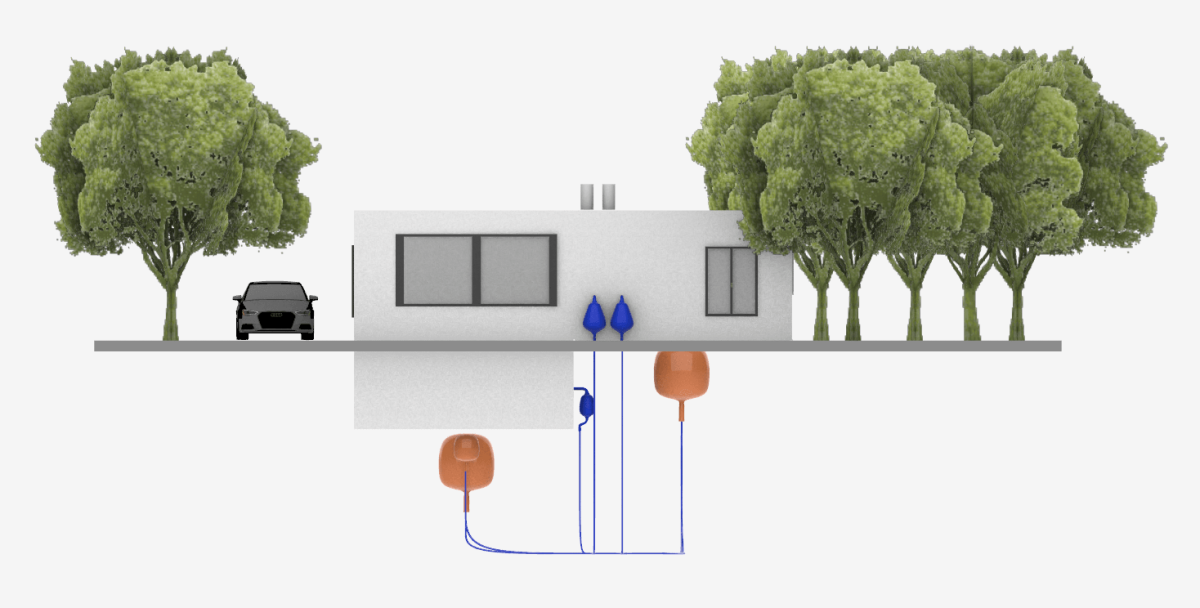

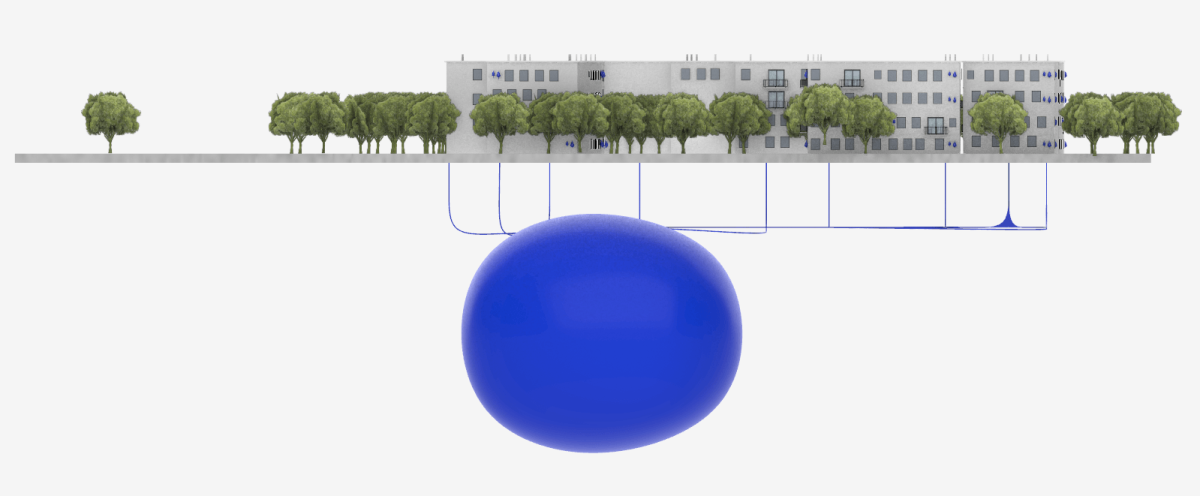

• The design of things along the new timeline – hypothetical products, advertising campaigns, images, texts – as evidence of the new value system in action. In a longer project this can culminate in well-rendered imaginaries of an alternative present.

Perhaps the most vital use of counterfactuals in design, and its most valuable contribution to design education, is the possibility for different paths to emerge that were drowned out by the dominant or ‘standard’ narratives. Conjuring into being or simply recognising alternative histories can open up valuable future paths, and create space for rich new possibilities and new imaginaries to flourish.