The community resilience approach, developed as the Mediterranean speculative approach, deals with future implications of major global changes (technological, economic, political and environmental) in the local context, through the application of speculative design practice. It was developed in the Adriatic – the periphery of Europe, away from the urban and technological centres, in the contexts where we live and with the people we understand.

For Ezio Manzini 1 , large-scale change is only possible as a result of a cumulative build-up of small-scale radical changes. The same strategy has been articulated with different wording by the Trojan Horse collective, who claim that concrete action need not take the form of a grand intervention, but that modest gestures may suffice. Manzini explores the potential of such transformative change, pointing out that a significant number of social movements that attained public recognition, and have been subject to public administrative regulation, started as bottom-up initiatives, launched and maintained by small groups of individuals, in a rather activist style, often working out of reach of the legal system. Bottom-up and participative approaches are important, since they transform the prevailing understanding of design as human-centred, based on the notion of the designer as an author accompanied by the mystification of design practice (and designed objects). Instead a designer is (and should be) the one who transfers methods, tools and techniques to the community, while also facilitating understanding of the processes happening around them and revealing the anatomy of the system.

Within this approach it is important to engage the local community, both experts and ‘ordinary’ citizens, through a whole range of possible future scenarios. Those community actors are not only ‘consultants’ in the process, they are participating in the design process, bringing their vision via scenarios and various design concepts, encouraging discussion and awareness about possible futures. Although outcomes may lack concrete actions outside the context of the project, the participatory process between designers, experts and citizens opens up potential models of the future that can be built on community resilience. This process, occurring through imagination, but also the design of ‘real speculations’, relies on cooperation, not competition.

Speculation is a tool or a method for social exercises, and the mediation of skills/competencies/knowledge needed for better orientation in new situations and contexts of the near future. Even when they do not have a specific or “useful” result, the speculations generated through practice or educational activities stand as a valuable accumulation of opportunities, skills, scenarios and hypotheses. By transferring our (designers) methods and tools we could support individuals and the community to act. Moreover, going beyond the speculative practice leads us to gradually go beyond the idea of just “predicting” the future by creating possible paths and actionable plans needed to achieve a better, i.e. preferable future.

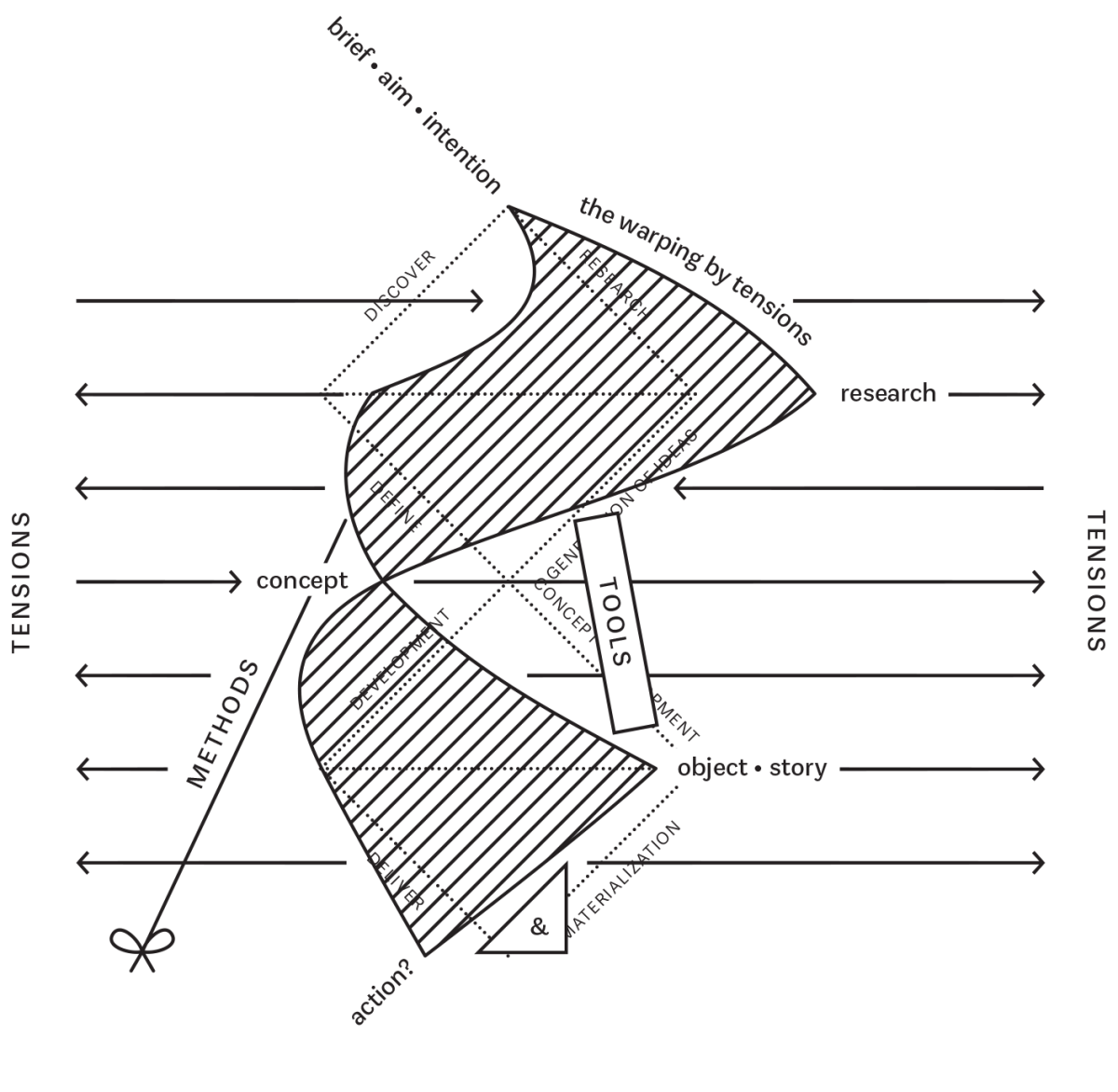

The process is based on the traditional design process starting with (1) the brief and theme, followed by (2) research and development of the (3) background story as a context for the (4) concept, communicated with the (5) designed outcomes, (6) presented/participated to the public and (7) evaluated and reflected in the real word/present. This process, during the whole development, is shaken and steered by the series of tensions, with corresponding scopes, which have been detected during the SpeculativeEdu project. Tensions, in the interplay that educators and students need to address when designing speculations, can open paths of critical reflection that lead to informed experimentation, to better conceptualise, deploy and evaluate not only designs but also the debates that surround them and the audiences that encounter them.

Double Diamond Vs Tensions: By focusing on the tensions the design is derailed from the "traditional' design processes and outcomes

This approach was primarily tested in short and intensive workshop mode. Workshop models have proven to be particularly inspiring within multidisciplinary groups, where the critical and speculative approach is a cohesive element between different disciplines and professions. Workshop-based, multidisciplinary practices, offers the opportunity to introduce different educational approaches, which go beyond, existing, slow and constrained curriculum-based academic programs. On the other hand, individual approaches at the master’s level have proven to be suitable for projects that have an open approach to methods, techniques, and tools and which, specifically for the needs of individual projects, form a corresponding set of necessary methods and tools.

To summarise, the approach is based on:

✤ Implications in the local context,

✤ Collaboration with experts,

✤ Participation of the local community/people/associations.

This approach intends to bring out the following:

✤ Possible future scenarios,

✤ Real speculations,

✤ Help (us/others) to understand current processes and the system,

✤ Transfer of methods, tools and techniques,

✤ Introduction of cooperation instead of competition,

✤ Transfer of local changes to the global level/context,

✤ Aim for possible “broader” transformative results.

With the aim of achieving the following outcomes:

✤ Opening discussions/raising awareness,

✤ including experts and local community (in the participatory process),

✤ Achieving visible/real results/outcomes (in the context of the project) / transferring tools/methods to the local context (to experts and community),

✤ Going beyond individual projects local level to broader outcomes/visibility/transfer.

As Manzini notes these various (bottom-up, peripheral) changes, the loci of the most interesting social developments of and the origin points of novel ideas and behaviours with the potential to become widespread, too often remain within the confines of the very system they labour to upheave. To effect real change, what is needed is, above all, continuity and coordination among those various small-scale movements. Ana Jeinić calls for an “emancipatory speculative design” philosophy, a kind of open-ended utopian collective praxis in search of new means of production and mediation in design, and of new forms of synergy with both institutional and extra-institutional subjects. One of the challenges of the SUrF project is how to make this approach (pivot) transferable and useful in different contexts.

- Life Projects: Autonomy and Collaboration. (2019). In Manzini, E., Coad, R.A. (Trans.). Politics of the Everyday (pp. 35–68). London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350053687.ch-002 ↩