This interview was conducted on July 3, 2024 during the Deleuze and Guattari Studies Conference & Camp at the Faculty of Architecture and Built Environment of TU Delft. It explores critical intersections between architectural education, speculative thinking, and the role of drawing as a mediator of theory and philosophy. The conversation critiques the insular nature of contemporary architectural pedagogy, advocating for an interdisciplinary and transgressive approach that rethinks traditional teaching formats by pushing their boundaries and intertwining them. The interview also investigates Kodalak’s teaching philosophy, deeply influenced by the notion of worldbuilding – a creative and speculative process that blends architecture, philosophy, and fiction. The discussants also reflect on the role of drawing, positioning it not merely as a representational tool but as a form of thinking that complements and challenges textual narratives, encouraging deeper philosophical engagement and speculative exploration.

Before we begin, let me provide a brief introduction to the research project. Earlier this month, in June, we organised a workshop titled "Sensing-Intuiting-Imaging (SII)" with MSc2 students at the Faculty of Architecture and Built Environment at TU Delft. This workshop drew on Gilbert Simondon's concept of the imagistic cycle, which comprises four phases: motor-image, perception-image, symbolic-image, and object-image. The aim was to foster speculative and intuitive problematizations, cultivate new forms of sensitivities, and explore new methods of expressing these potentials—essentially, to develop innovative speculative approaches to thinking and practising architecture.

Having that in mind and based on your experience, what do you perceive as the strengths and weaknesses of contemporary architectural education? Which aspects do you support and embrace and which do you find problematic if any?

I find the blind insistence of the academy to operate within insular siloes misguided. It is unfortunate to witness so many historians, theorists, and designers mistaking the vast potentials of architecture with the self-imposed limits of their narrow disciplinary horizons.

I rather pursue alternative pedagogies that engage the architectural field as a continuum, indifferently transgressing any artificial set or border.

Which formats of architectural education do you find most useful and effective? Additionally, which formats do you apply in your teaching practice, and for what purposes? What are your thoughts on the established formats of teaching, such as design studios, workshops, lectures, and seminars? Are there any advantages and disadvantages associated with their frequent application?

I experiment with a wide variety of pedagogical formats at different schools: comprehensive core lectures at large auditoriums; highly specialised electives in intimate classroom settings; dialogical seminars co-taught with insightful colleagues; design studios for first- and last-semester students at both the beginning and end of their educational journeys, etc.

All such formats can and do easily become banal and restrictive if you choose to remain within their orthodox frameworks. Things start to get interesting, once such frameworks are pushed beyond pedestrian expectations.

I tend to experiment with interfusing the formats with one another, approaching architectural pedagogy akin to the transmutative concoction of an alchemical potion. As in catalysing the unlikely intimacy of a conversational course with a hundred students in an auditorium, rather than succumbing to the distancing comfort of unilateral lectures. Or, giving multiple philosophical workshops on the likes of Spinoza and Bateson, David Foster Wallace and Virginia Woolf, interspersed throughout various stages of a hardcore design studio, rather than focusing solely on standard form finding exercises, or contending with the linear setup of administering a formative theoretical framework first and expecting a practical outcome last. Or, facilitating a theory elective to produce a rigorous worldbuilding project with various layers of construction from space-time modalities, astrological features, and sociopolitical formations to flora, fauna, and architectural conditions.

There is surprising fecundity in witnessing studios culminating with deep philosophical introspections, philosophy seminars giving birth to meticulous design projects, cold auditorium-level lectures embracing the impromptu dynamism of heated, high-stakes conversations.

How would you define speculative education, and what thoughts does this concept evoke in you? Where do you see potential for developing innovative speculative approaches in the teaching and learning of architecture?

I am lately obsessed with the activity of worldbuilding, teaching a novel course that brings together architecture, philosophy, and fiction. This new tunnel vision is also tempting me to reconsider teaching as a worldbuilding activity itself, from designing the rhythmic pulsations of the syllabus and critical tempo of the semester to breathing life into a vast pedagogical plane of existence with various formats and contents.

What is education, in the end, if not the combined activity of teachers and students to build either new worlds, or rebuild the current world anew, which is actually one and the same thing approached from different angles.

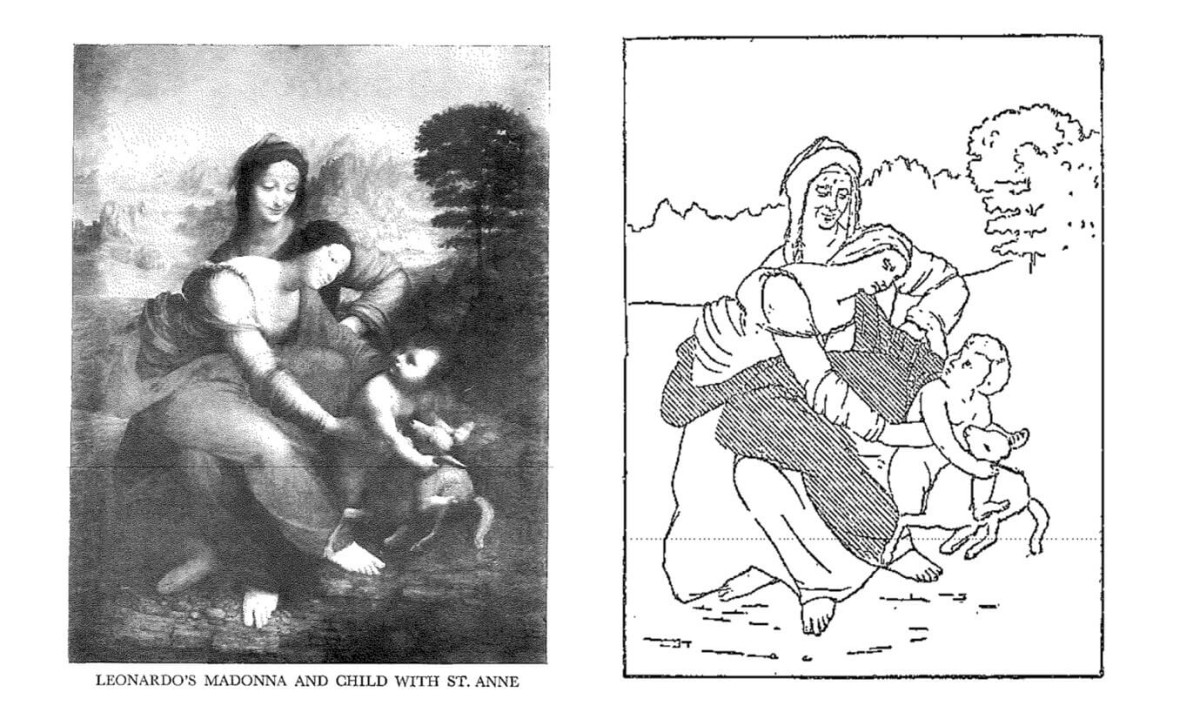

Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, is primarily known for his theoretical work, clinical practice, and the development of psychoanalytic theory, which he disseminated through writing, case studies, and correspondence with colleagues. While Freud had an interest in art and collected various artefacts and antiquities that influenced some of his ideas and metaphors, drawing was not typically a part of his professional repertoire. However, in his first and last large-scale excursions into the field of biography, his manuscript Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood, where he applied the methods of clinical psychoanalysis on the life of a historical figure, Freud produced linear contour drawings to illustrate Leonardo da Vinci's renowned painting Madonna and Child with St. Anne. These drawings aimed to support his psychoanalytical hypothesis about the childhood of great artists. Freud argued that for Leonardo, the two maternal figures of his childhood were merged into a single form:

“One is inclined to say that they are fused with each other like badly condensed dream-figures, so that in some places it is hard to say where Anne ends and where Mary begins. But what appears to a critic's eye [in 1919 only: 'to an artist's eye'] as a fault, as a defect in composition, is vindicated in the eyes of analysis by reference to its secret meaning.”1

In your articles, conference presentations, lectures, and other disseminations of your research, you create similar contour drawings. What I find particularly intriguing is how, much like Freud, you apply these drawings in highly theoretical works, creating a fascinating intersection of theory and practice. Thus, how do you categorise these works in terms of their level of representation and abstraction? Do you consider them architectural drawings, illustrations, or diagrams? And how do you differentiate architectural drawings from architectural diagrams and illustrations?

I find drawings, in all their modes and manners, fascinating expressions. As architects, we are very fortunate to have been introduced to various techniques of drawings, from the most bureaucratically technical to the ecstatically evocative. Yet any interesting companionship with drawings requires, first, a process of unlearning their strictly architectural functions and representational reductions, so as to unearth their hidden capacities of expressing different moods and modes of life.

I tend to introduce drawings, and mostly skeletal diagrammatic drawings, to most of my discursive works from essays to lectures, you are right, as I find the gestural continuity and creative tension of lines within texts and drawings highly rewarding. Lines fascinate me, finite and infinite lines, curved and orthogonal lines, dashed and dotted lines. So much so that, at times, I find myself almost subscribing to a metaphysics of lines, constituting the ever-changing vectors of life, as I tried to flesh out in my essay on David Foster Wallace: “Static, dynamic, and ecstatic, lines manifest vibrant modes of life. Worlds are made at their crisscrossing. Lines constitute suburbs, kids, and tornadoes alike.”2

What is the purpose of these drawings in your research practice, and how and when do you utilise them? What are your thoughts about drawing as a speculative medium in architectural education? Do you consider drawing as a form of thinking, and what approaches might emerge from this perspective?

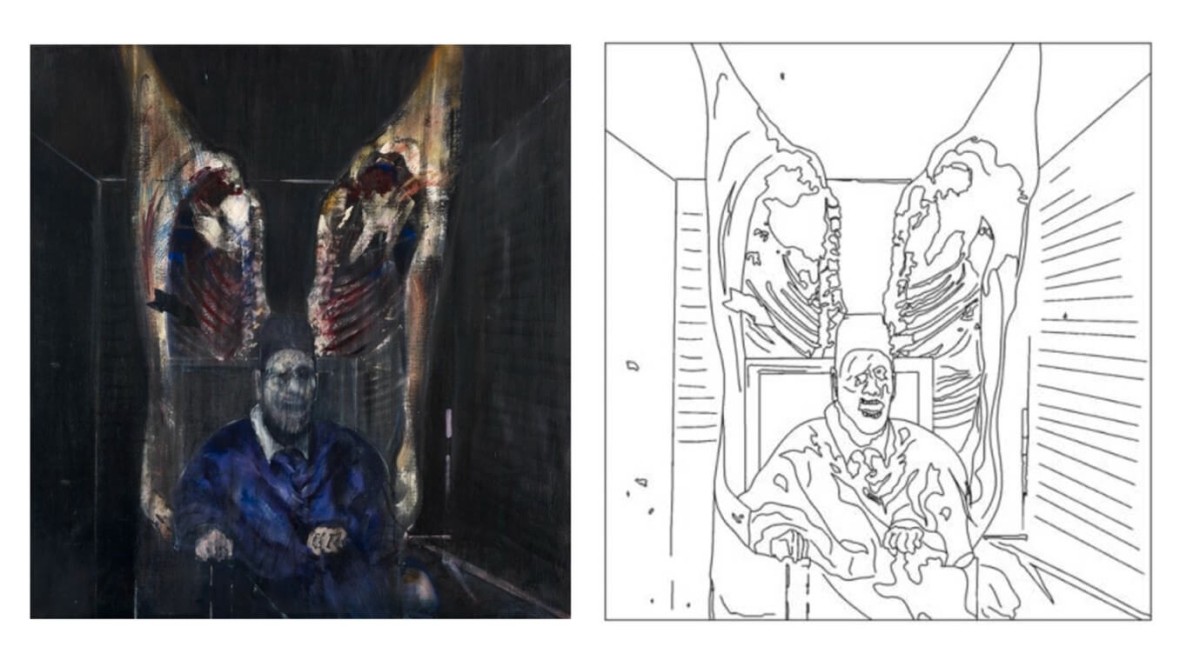

Drawing is a problem of creation. In philosophical texts, research projects, and academic lectures, my purpose is almost always doubling a textual expression with a visual one. Yet neither to fill in its gaps, nor to repeat the same message now in a different medium, nor to strengthen its supposed clarity of communication. But to challenge the text with the drawing, and to question the drawing with the text. My primary interest is exploring an area of magic that emerges only when one reads a few pages, then surveys a drawing, then goes back to reading, and vice versa. Such zigzagging navigation from text to drawing and from drawing back to text lights up a critical ecology of mind, facilitating the rare cooperation of imagination, conception, and intuition.

Similar to Freud's approach, your drawings serve as a medium for conveying strong theoretical concepts. What are your thoughts on the transduction of philosophical ideas into drawings? What, if anything, is lost in this process, and what is gained?

Concepts are extra-linguistic constructs. At times, they can express themselves with more vigour in painting or music than oral narrative or written text. It is not a coincidence that even the philosophers and system-building thinkers themselves could not resist the allure of drawing visual diagrams to express specific dimensions of conceptual movements (from Spinoza, Al-Hallaj, and von Uexküll to Bergson, Freud, and Deleuze).

In this sense, the dangers of addressing concepts in visual form are not more or less than expressing them in linguistic form—as both require translating pre-linguistic and non-visual dimensions of life.

You are too kind to use my name in the same sentence with Freuds and Leonardos. I rather see my experiments of cross pollinating texts and drawings at most in an embryonic stage, helping me in adapting conceptual subsystems of thinkers and makers resonant with my own. They are yet to help give birth to conceptual systems distinctively of my own.

Figure 1 – Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, c. 1501-1519 © Public Domain

Figure 2 – Illustration from Sigmund Freud, Five Lectures on Psycho-Analysis and Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood, trans. and ed. James Strachey, in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 11 (London: The Hogarth Press, 1955), 1–98. Originally published 1910. © Public Domain

Figure 3 - Francis Bacon, Figure with Meat, 1954 © Pictoright Amsterdam 2024

Figure 4 - Illustration of Francis Bacon’s Figure with Meat © Gökhan Kodalak 2018

- Strachey, J., Freud, A., Strachey, A., Tyson, A. & Richards, A. (1957) The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XI (1910): Five Lectures on Psycho-Analysis, Leonardo da Vinci and Other Works. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud 11:114. ↩

- Gökhan Kodalak, “Lines, Tornadoes, and David Foster Wallace,” Log 51 (Spring 2021): 172-82. ↩