Designing in Coexistence – Reflections on Systemic Change was published as an outcome of the discursive programme of the Croatian pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia (2023).

1The past

Design and architecture, since their rapid development during the 20th century, have played an uncritical supporting role to industry and the applications of technology in our everyday life.1 Most of the time, without reflecting on the implications of their actions. Unfortunately, they have lost their connection with the original modernist principles, such as a holistic view of the world and ecosystems and the support of technology and science for adaptation to and taking care of existing ecosystems. As the drivers of consumerism, architecture and design had their role in the foundations of the so-called Anthropocene (or Capitalocene), which has, more than ever in human history, brought extreme catastrophic scenarios that are likely to take place in the near future.2 This implies changes in our living environment but also social, economic and political relationships, changing power relations, bringing new social inequalities and new distributions of opportunities. Nature does not care about us. It will already adapt to the changes. The microorganisms from which life on Earth started are probably the last to remain, as hope for some new life. The accumulated influence of humans on climate change has already been determined several centuries in advance. Our activities have defined our successor’s futures. The time of comfortable life and extraction of natural resources has passed.

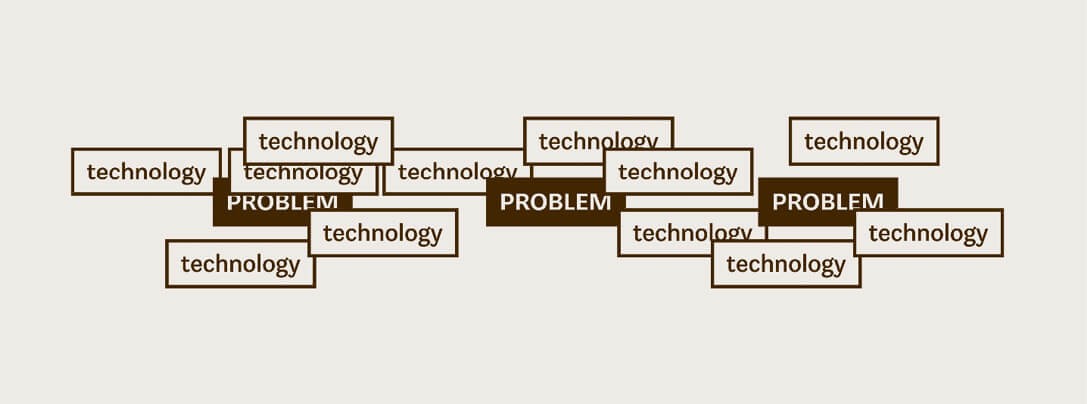

Human-centred design continues to contribute to global extractivism and resource exploitation through solutionism and failed manufacturing, production, and distribution systems. This paradigm in design and architecture, referenced as “Western melancholy”, is rooted in a worldview that “we have always been and we continue to resolve problems with technology” and that “the future will be hyper-ultra-turbo interesting!”.3 This belief celebrates the Western position where humans evolved from natural ecosystems into creators, and in the name of progress and growth, they can and must change nature, while resolving the consequences of their actions using science and technology. This is based on the idea of a civilization that is separated from nature, which, through the industrial revolution and the development of a capitalistic economic system, has led the planet to its current state in the Anthropocene. It is embodied in an architectural and design practice which has “consistently failed to imagine future possibilities beyond globalized capital”.4 Unfortunately, these actions in making the future have resulted in unmaking other futures.5 This has been broadly criticised, for example, by Ursula Le Guin as “techo-heroic”6 or by Donna Haraway elsewhere7 .

Western Melancholy (Mitrović & Šuran, 2018)

Climate change is the most significant present catastrophe, but we also face a series of crises that run parallel, such as the pandemic, the current threat of global nuclear war, permanent migrant crises, and others. All these crises are intertwined and they reveal the fragility of existing infrastructures and ways of life, bringing us visions of dystopian futures, facing the fact that the future did not turn out as we expected. For instance, for someone who was a teen in the 1980s, the future looked exciting, e.g. as in the series of films “Back to the Future” by Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale, which brought the idea of exciting tech gadgets apparently available to everyone. Unfortunately, the future today is getting closer to the dystopian one of P.D. James and Alfonso Cuarón from “Children of Man”. We are becoming scared of the future, we are afraid of what tomorrow will bring – is it a new disaster or a new dystopia that is waiting for us in the near future. At the same time, we are increasingly nostalgic for a past where we had hope for a better future and when it looked like we had control over the future. Unfortunately, “our” future is less and less possible, limited by our past, shaped by the failure of modernistic ideals of the holistic views of society and the planet.

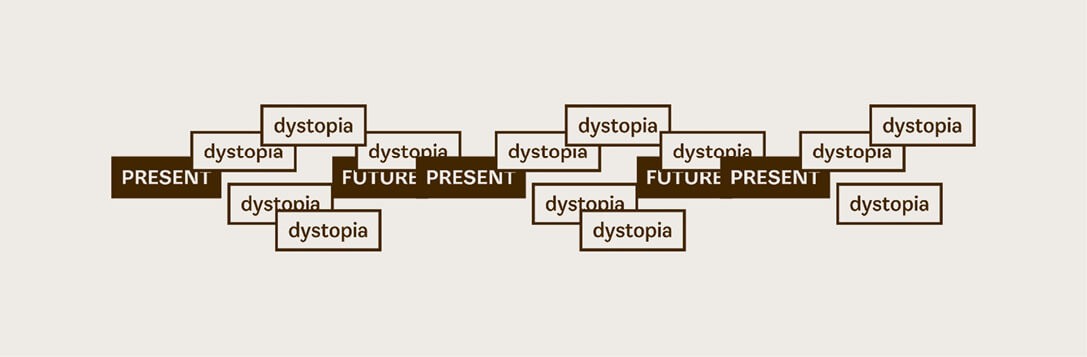

Michael Smyth discusses Anthony Dunne’s concept of “broken futures” as a promise of past “peak” futures that have failed to be delivered, leaving us with just “pale shadows”.8 For Smyth, we are seemingly bound to the “spectres of the past”, utopian imaginations as “the world of flying cars and jet packs for all, each somehow encapsulating the promise of a future so far removed from the everyday reality and so beloved of fictional secret agents of the time”.9 Consequently, looking in the everyday context, at the general level, we are witnessing a disconnection from the future, giving the impression that the future is hostile and that there is no place for us in it10 , resulting in the feeling that we do not want to be part of such a future anymore. Of course, there are still glimpses of desirable, positive futures, but those futures are most of the time distant and elitist, not including us. The diagnosis has been made – we have gradually given up on the future.11 Futures colonized by the dominant economic model have led to the fact that it seems we have lost the ability to imagine alternatives in our everyday life, what is possible, what is probable, and what is preferable. The dominance of and demand for dystopian scenarios in popular culture in the last two decades has led to people considering catastrophic scenarios as inevitable, moving away from imagining different futures, and becoming passive instead of proactive. Tony Fry points out that the future we create never starts from zero, an empty space waiting for us to fill it, but it is pre-colonized by our past and other visions of the future.12 The present, referred to as dystopian futures, most often generates the same dystopian futures again.13

Temporal loop (Mitrović & Šuran, 2018)

The once-dominant world model, reveals itself as fragile, broken and highly unsustainable, showing that its future continuation is uncertain. This raises questions about how we represent it, how we adapt to it or challenge it, and how to imagine and speculate on other possible, probable and preferred worlds. There is a need for all professions to look into more radical and innovative practices and methods. Today, the majority of designers and architects still use tools, methods and approaches which seemingly do not fit the present reality anymore. Current methods have largely evolved from models established in the early 20th century, adopting a global approach towards resources, solutions, and systems of production and distribution, and as such, seem inappropriate for the world of today. Design and architectural education still do not include all necessary variables (or voices) in the educational process. We still design for today, not for tomorrow, still work for and within the dominant system, and still teach design as the world is. We are still not ready for radical changes.

Could design and architecture, through practices from pragmatic to speculative, from discursive to activist, and as multidisciplinarity activities, bring reflexive, imaginative, and generative pathways toward different futures? Both design and architecture, as fields of practice, have the potential to detect, mediate and generate new relations and to encourage radical imagination. This potential has been documented and discussed over more than 20 years of speculative design and related critical and future-orientated practices.14 Those practices have contributed to the development of design and architecture as worldmaking agents, bringing possibilities in exploring diverse versions of the world, helping us understand our environments and develop our capabilities to transform them. Speculative design has been used successfully as an experimental environment to test different hypotheses about our lives in the future.

2The present

Speculative design has been both praised and criticized for its ability to create future dystopias as a kind of “salvation” or a fresh start, with the hope that such circumstances, as a “tabula rasa”, may potentially lead to spontaneous new transgressions of society. However, this approach neglects the pressing crises of the present moment. Looking back at speculative practice, there are many projects dealing with dystopian futures, including disasters such as diseases, wars, climate disasters, totalitarian states, technological dystopias, etc. Arguments like “we told you so”, “you didn’t prepare” or “you did nothing to avoid this” are now used within the speculative community to critique society’s status quo over the many years. Those fatalistic views, based on the thoughts that there is nothing possible to do now, have also led to despair and toward a state of practice where dystopia becomes the new normality.

Current-day speculative, critical, and future-oriented approaches in design and architecture seek to encourage action and achieve changes in the real world. They reflect a series of criticisms that these practices have been appropriated by the consumer society in “imagining luxury fantasies for the one percent, whether it is in the form of lab-grown meat, extra-planetary colonization, or augmented interfaces for consumer electronic”.15 These practices do not presume to change the world in one fell swoop, nor do they hope to eradicate prevalent socio-economic structures overnight. Yet, they can indeed initiate a series of bottom-up changes and restore hope in the future and reimagine the unseen horizons it holds. To achieve this, speculative practice works to gradually replace the idea of “predicting” the future by creating possible paths and actionable plans needed to achieve a better, i.e. preferable future. As a pedagogical tool in an educational curriculum, they could help students and educators to understand the context and consequences of their design practice. The interplay between tensions that educators and students need to address when designing speculations can open paths of critical reflection that lead to informed experimentation, to better conceptualise, deploy and evaluate not only designs but also the debates that surround them and the audiences that encounter them.16

We see around us a growing number of design and architecture projects which are free from any need for glamorous, self-serving provocativeness, relieved by visions of a technology-centred (techno-heroic) future.17 Arturo Escobar described this shift as the progressive transformation in the nature of design, moving from a process primarily led by experts to produce various objects and services suitable for the prevailing socio-economic order, which itself remains unexamined and unchallenged, towards a new kind of design practice rooted in participation, aimed at society, and valuing an openness which allows questioning and re-evaluation of the most commonly accepted ways of conducting business and managing production and consumption.18

These bottom-up and participative approaches19 are important since they transform the prevailing understanding of design and architecture as human-centred and Western-centred disciplines, based on the notion of the designer as an author accompanied by the mystification of design practice (and designed objects). A designer is (and should be) the one who transfers methods, tools and techniques to the community, while also facilitating understanding of the processes happening around us and revealing the anatomy of the system itself.

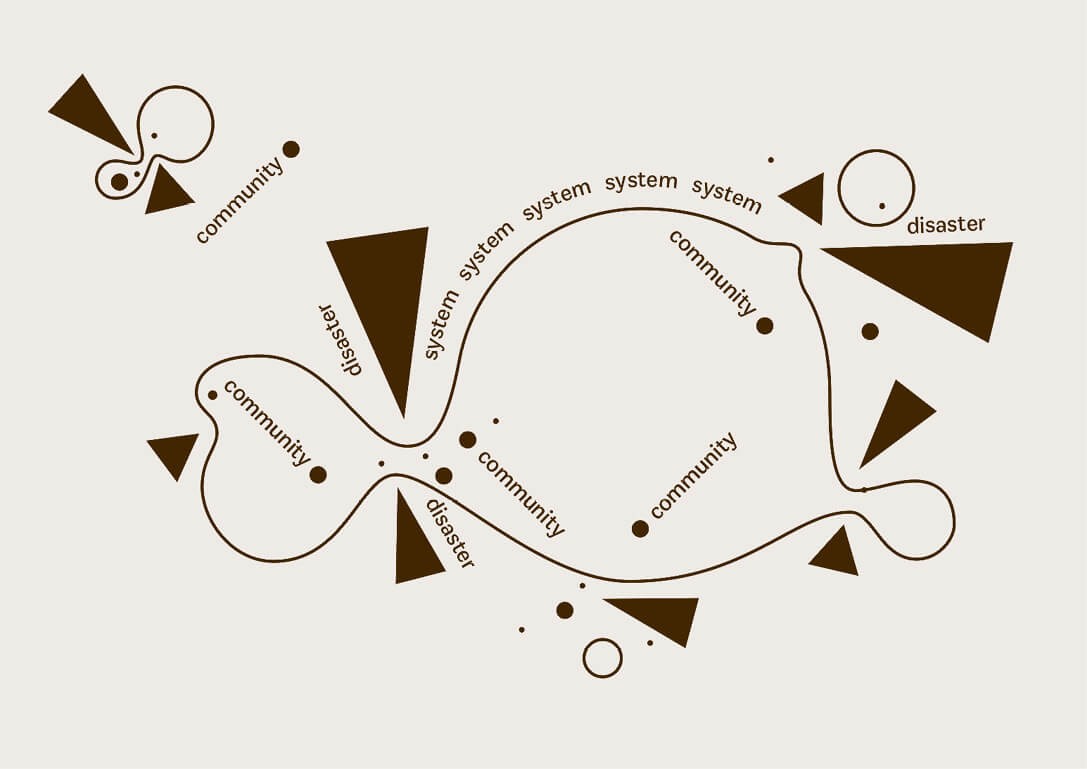

A Practicum of Resilience: Split, 2021 (Mitrović & Šuran, 2021)

However, those participatory approaches in design and architecture still operate within the same system, whether it is the dominant global economic capitalist system, energy, communication, education system or something else. Without questioning the supply chains of food, water, energy and others, we lack insights into how those systems work because they become hidden from us. Additionally, despite their participatory nature, such practices often involve only privileged participants (activists, cultural workers, academics, NGOs and so on) and do not reach those who are marginalised in society. When viewed as a whole, the current “system”, though repeatedly perturbed and shaken by various disasters, remains still fairly homogeneous and resistant to change. The challenge is to mitigate and unite often disparate practices, bridge the conceptual gap between global and local action, and mediate between central and marginal, toward creating a new global “utopian imaginarium”. How to work together on devising practical, actionable pathways toward the goal of systemic transformation and transition?

In the long history of living on this planet, people have become accustomed to living with crises and disasters. Looking from a Western perspective, after years of the Western’s world “prosperity”, disasters are becoming the new normality, the reality in which people must build new resilience. Superflux stressed that “we need to evoke in people the hope that lies beneath the anxiety and we are more resilient and more able than we are being led to believe and that this resilience cannot, however, be accessed within the anthropocentric paradigm”.20 Studying autonomous resilient communities in our (Adriatic) region gave us insight into those small communities used to living and surviving on the margins of the system, which maybe could have more chances to survive in such futures.21 Our discussions with these communities have shown how important education is, especially direct and informal education, in achieving resilience. On a global level, we repeatedly see new (post) disaster landscapes, novel forms of communities, resistances, agencies and innovations for building different and diverse everyday lives.22

The Croatian pavilion at 18th International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, titled “Same as it Ever Was”, is an ode to the ambiences of coexistence of the wild and the domesticated, natural and fabricated, inanimate and living. It evolves from documenting the Lonja Wetlands, one of the largest protected aquifers of Europe, in which dynamic environments have evolved from centuries of symbioses between a landscape in constant flux and communities adapting their lives to it.23 If we take a long-term perspective, our lives are comparable to those of butterflies or insects in the Lonja Wetlands, which last a short time in our frames of reference. Nature and evolution move slowly, over millennia, millions of years. If we take small transformative action steps now, persistently and systematically, we could expect long-term changes, first small ones, and later in possible synergy with other such movements, changes that can still bring hope for a positive future. For Ezio Manzini, large-scale change is only possible as a result of a cumulative build-up of small-scale radical changes.24 The same strategy has been articulated with different wording by the Trojan Horse collective, who claim that concrete action need not take the form of grand intervention, but that modest gestures may suffice.25 Manzini, however, notes that these various (bottom-up, peripheral) changes, the loci of the most interesting social developments of and the origin points of novel ideas and behaviours with the potential to become widespread, too often remain within the confines of the very system they labour to upheave.26

To effect real change, what is needed is, above all, continuity and coordination among those various small-scale movements. Ana Jeinić calls for an “emancipatory speculative design” philosophy, a kind of open-ended utopian collective praxis in search of new means of production and mediation in design, and of new forms of synergy with both institutional and extra-institutional subjects.27 Ezio Manzini explores the range of potential of such transformative change and points out that a significant number of social movements that have over time attained public recognition, and have been subject to public administrative regulation, started as bottom-up initiatives, launched and maintained by small groups of individuals, in a rather activist style, often working out of reach of the legal system.28

Despite criticism that throughout history, avant-garde movements in design and architecture have not achieved significant social changes, that they either disappeared or were appropriated by the system, they have still left behind them strong foundations, which build up the practice, especially in the educational context. Speculative practice remains a valuable tool for understanding the processes taking place around us and showing us some possible alternative action paths to the future. By speculating about the future, we begin to act now and in the present. Although speculative projects do not provide solutions to “wicked problems,” they have introduced new approaches, methods, and tools that are now available in our designer’s toolbox, enabling us to act towards different futures.

Through the SpeculativeEdu project, which dealt with education in the context of speculative design and related practices, a line of guidelines was proposed as new directions that could lead to a “beyond” or “post” speculative design practice.29 Taking into account more than 20 years of practice and strong criticisms and reflections, these challenges were detected to open up new possibilities for design to contribute to transformative changes, starting with education. These guidelines deal with the challenges that if we are going to reclaim the future we need to start from the present and we should start with actions “now and here”. That we have to focus on the “real world” and remove ourselves from the glamorous dystopian world. That we could learn a lot from looking at margins in a periphery and that design practice is in collaborations, and it is primarily local. As well, we should not forget that design always has consequences and that speculation is our duty, not a privilege.

3The future

Speculative and related design practices, directed towards the future and new social contexts and organizations, reflect on the historical misconceptions of modernism. Cameron Tonkinwise emphasises that the current role of speculative design is to provide answers to the mistakes of the modernist project and to re-materialize its visions of a radically different future in our everyday lives.30 Not rejecting but refocusing and recontextualising the use of science and technology in our relationship with the planet. The neo-colonization of the future could be avoided by building a future based on inclusion and solidarity, looking from the interspecies perspective, not only at the level of the individual communities but also at the global, planetary level. However, given the limited time we have left to react to climate change, the only way forward is to act immediately, to start here and now to initiate social changes, even starting from toxic lands and destroyed landscapes. A radical change in our relationship with nature is necessary to rebuild destroyed ecosystems. Movements like permaculture and degrowth, including the most radical ones such as “pirate care”31 , are certainly driving change from the bottom-up and they offer models of different futures. The goals of the transition movements largely coincide with the goals mentioned here (resilience, transition, social changes, etc.). They generate projects that build a better society and future and we can learn a lot from them. However, what we can and should offer through design and architecture is a step further, by coming up with visions and scenarios that go beyond, that bring inspiration, but also new possible approaches and concrete pathways.

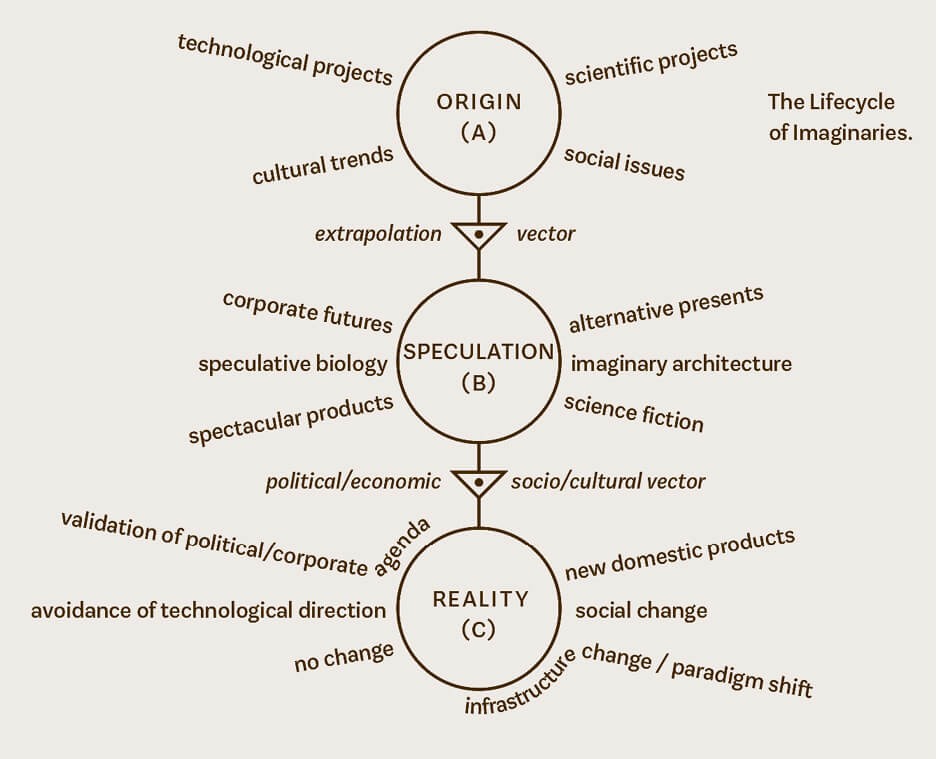

The Lifecycle of Imaginaries (SpeculativeEdu, 2021)

The editorial of the Temes de Disseny journal titled “Emerging Habitats. Design as a Worldmaking Agent” stated that “design is and has to be a transdisciplinary field in which the main aim is not to attempt to solve the ‘wicked problems‘ we face in the present, nor to ‘divinate’ the future, but instead to identify shared concerns within these present problematics, and to devise conceptual grounds and transversal methods and approaches that potentialize the productive aspects of design”.32 Non-conventional modes of design, including speculative, transitional, pluriversal and related approaches could imagine pathways in transition from present states and conditions to long-term desirable futures.

Speculative approaches have the potential to intuit and speculate, rather than predict, solve or correct. They deal with the different economic and social models, moving away from the idea that well-being is only possible with economic growth and looking for radical change in relationship with nature. Challenging the widespread view that cooperation is less important than competition.33 Going beyond just designing imaginary worlds of the future toward how to design for it and design for the world what would be. Discussing and detecting the constraints that stop from doing different designs to investigate how design methods could change to adapt to the current crises and offer “alter-natives”34 .

Consequently, the possible path of the future trajectory for design and architecture can be seen as a continuation of efforts on the local level, working in a close connection to the “social periphery”, or margins, in the local context that one has come to know so closely.35 Although these activities, initiated and limited to the local-level change, could look like a kind of personal or group psychotherapy or self-help ritual that restore hope for the future, they are extremely important as a seed of change. These efforts should aim to provide practitioners and educators with a toolbox of methods, tools, and techniques that can be transferred to future generations, with the hope that they will start new activities, bring a broader spectrum of participants, and exponentially increase novel approaches focused on change.

This process could bring about needed positive visions and hopes, new imaginations of the worlds of the future, and new “real utopias”. Looking back, most historical utopias have been built as important and successful critics of the social, economic, political or technological context of a particular time. Unfortunately, we have also seen utopian projects that, in the end, have failed as closed systems or ended up as elitist or autocratic communities. We could learn from those failed projects as a consequence of the world’s particular social and political state. In the search for alternative paths to dystopian ones, James Auger and Julian Hanna discuss “atopia” as a direction that “rejects both the escapist fantasy of utopia and the nihilism of dystopia, favouring instead a conceptual middle ground from which real-world conditions can be productively engaged and challenged”.36

4The hope

Mark Fisher, in his famous, but gloomy book, describes “capitalist realism” as the reality in which we live and from which there seems to be no way out, no future.37 However, at the end of the book, he concludes that “even glimmers of alternative political and economic possibilities can have a disproportionately great effect” and that “the tiniest event can tear a hole in the grey curtain of reaction which has marked the horizons of possibility under capitalist realism”. Going beyond rationally based forecasting, which is most of the time limited to the current system, speculations could open those horizons.

Lesley Lokko, the curator of 2023 International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia included in her call a strong component of education as “a kind of laboratory of the future, a time and space in which speculations about the discipline’s relevance to this world — and the world to come — take place”.38 We should look at our universities as “laboratories” embodying continuous interdisciplinary processes realized through situated education, focused on futures. The topics to be explored are numerous, looking at them from the perspective of how they impact education and how education in design and architecture can respond to the demands and challenges of the 21st century.

• How to imagine alternatives, what is possible, what is probable, and what is desirable?

• How to redefine our relationship with nature, is it possible to create a new coexistence as a path for different futures?

• How to learn from and respect marginal communities used to living and surviving in/with nature?

• How can we work together more effectively as one towards the goal of achieving radical imagination and systemic transformation and transition?

• How could small steps bring long-term changes in the near future, or do we need a radical change now?

• What are the constraints that stop us from doing different designs and architecture for the future?

• What approaches, tools, methods and mechanisms could give transformative power to the design and architectural practice?

The Aquatics (Interakcije 2023: Homo Aquaticus Workshop, 2023)

In “hard times coming”, we hope that educators and students together can be “realists of a larger reality” from Ursula Le Guin’s call39 . Future visionaries who will imagine “real grounds for hope” and how the realities of people could be different. We are interested in how education can initiate changes and what actions support this process. Redefining our relationship with the changing nature, shifting from competition to cooperation, needs different approaches, tools, methods and mechanisms. Is it possible, and how is it possible, to reclaim positive visions of the future and what is the role of education in this process? Starting from the worldmaking potential of design, urbanism, architecture and art (including other related disciplines and practices), we are investigating those challenges, here, from and in (but not only) the specific context of Southeast Europe and the Mediterranean, using speculations in real-world contexts by addressing the needs of diverse local actors and to reflect the impacts of omnipresent climate changes. Holistically looking at the world, starting here and now, from the local level to a broader context.

- Auger, J. (2023). Considered means and questioned ends?. In Mitrović, I., Roth, M. and Čerina T. (eds.) Designing in Coexistence – Reflections on Systemic Change. Croatian Architects’ Association. ↩

- Harriss, H. (2023). The “Future of Architecture” is for other species. In Mitrović, I., Roth, M. and Čerina T. (eds.) Designing in Coexistence – Reflections on Systemic Change. Croatian Architects’ Association. ↩

- Mitrović, I. (2018). “Western Melancholy” / How to Imagine Different Futures in the “Real World”? Interakcije. https://interakcije.net/en/2018/08/27/western -melancholy-how-to -imagine-different-futures -in-the-real-world. ↩

- Hine, A. and Charity E. (2023). Abyssal Hyperreality. Society and Space. https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/abyssal-hyperreality ↩

- Blauvelt, A. (2020). Defuturing the Image of the Future. Walker Art Center. Design for Different Futures exhibition. https://walkerart.org/magazine/defuturing-the-image-of-the-future. ↩

- Le Guin, U. K. (1986). The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. https://otherfutures.nl/uploads/documents/le-guin-the-carrier-bag-theory-of-fiction.pdf ↩

- Bryant, K. and Wallenberg, E. (2020). In the Heart of the Storm: An Interview with Donna Haraway. Science for the People. https://magazine.scienceforthepeople.org/vol23-3-bio-politics/in-the-heart-of-the-storm-an-interview-with-donna-haraway ↩

- Smyth, M. (2023). Future Tense – the challenge of imagining alternative futures. In Mitrović, I., Roth, M. and Čerina T. (eds.) Designing in Coexistence – Reflections on Systemic Change. Croatian Architects’ Association. ↩

- Smyth, M. (2023). Remix Culture: the comfort of nostalgia in uncertain times. UX Collective. Medium.com. https://uxdesign.cc/remix-culture-the-comfort-of-nostalgia-in-uncertain-times-b7e13a5851d5 ↩

- Bengston, D. N. (2020). Future Estrangement: Not Having a Place in the Emerging Future. Journal of Futures Studies. https://jfsdigital.org/articles-and-essays/vol-25-no-2-december-2020/future-estrangement-not-having-a-place-in-the-emerging-future ↩

- Berardi, F. and Fisher, M. (2013). Give Me Shelter. Frieze. https://www.frieze.com/article/give-me-shelter-mark-fisher ↩

- Fry, T. (2020). Defuturing: A New Design Philosophy. Bloomsbury. ↩

- Mitrović, I. (2018). “Western Melancholy” / How to Imagine Different Futures in the “Real World”? Interakcije. https://interakcije.net/en/2018/08/27/western -melancholy-how-to -imagine-different-futures -in-the-real-world ↩

- Mitrović, I., Auger J., Hanna, J. and Helgason, I. (eds). (2021). Beyond Speculative Design: Past – Present – Future. Arts Academy, University of Split. ↩

- Pater, R. (2021). CAPS LOCK: How capitalism took hold of graphic design, and how to escape from it. Valiz. ↩

- Encinas, E., Helgason, I., Auger, J., Mitrović, I. and Hanna, J. (2023). Speculative designs in educational settings: Tension-patterns from a (mostly) European perspective. 1-16. Paper presented at Nordes 2023, Norrköping, Sweden. https://doi.org/10.21606/nordes.2023.98 ↩

- Mitrović, I., Auger J., Hanna, J. and Helgason, I. (eds). (2021). Beyond Speculative Design: Past – Present – Future. Arts Academy, University of Split. ↩

- Escobar, A. (2018). Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Duke University Press. ↩

- Kothari, A., Salleh, A., Escobar, A., Demaria, F. and Acosta, A. (2021). Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary. Tulika Books. ↩

- Jain, A. and Sarsa, H. (2022). In practice: Superflux on the Future Energy Lab. The Architectural Review. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/in-practice-superflux ↩

- Mitrović I. and Šuran. O. (2021). A Practicum of Resilience: Split, 2021. https://vimeo.com/manage/videos/724026978 ↩

- Polleri, M. (2022). Our contaminated future. Aeon. https://aeon.co/essays/life-in-fukushima-is-a-glimpse-into-our-contaminated-future ↩

- Roth, M. and Čerina, T. (2023). To care is to know. In Mitrović, I., Roth, M. and Čerina T. (eds.) Designing in Coexistence – Reflections on Systemic Change. Croatian Architects’ Association. ↩

- Manzini, E. (2019). Politics of the Everyday. Bloomsbury. ↩

- Trojan Horse. (2020). Concrete actions are not necessarily a grandiose intervention. SpeculativeEdu. https://speculativeedu.eu/ interview-trojan-horse ↩

- Manzini, E. (2019). Politics of the Everyday. Bloomsbury. ↩

- Jeinić, A. (2021). To What End? Rethinking Design Speculation. Perspecta 54: Atopia. ↩

- Manzini, E. (2019). Politics of the Everyday. Bloomsbury. ↩

- Mitrović, I., Auger J., Hanna, J. and Helgason, I. (eds). (2021). Beyond Speculative Design: Past – Present – Future. Arts Academy, University of Split. ↩

- Tonkinwise, C. (2019). Creating visions of futures must involve thinking through the complexities. SpeculativeEdu. https://speculativeedu.eu/interview-cameron-tonkinwise ↩

- Graziano, V., Mars, M. and Medak, T. (2019). The Pirate Care Project. https://pirate.care/pages/concept ↩

- Roger, P. and Mariana, A. (2023). Emerging habitats: Design as a Worldmaking Agent. Temes de Disseny. Num. 39. https://doi.org/10.46467/TdD39.2023.8-19 ↩

- Šolić, M. (2023). A living planet: Pale Blue Dot. In Mitrović, I., Roth, M. and Čerina T. (eds.) Designing in Coexistence – Reflections on Systemic Change. Croatian Architects’ Association. ↩

- Avila, M. (2023). (De)signs as response. In this book. ↩

- Interakcije. (2022). Interakcije 2022 – Open Call. https://speculativeedu.eu/interakcije-2022-open-call ↩

- Hanna J. and Auger, J. (2021). The Possibility of Atopia: An Unmanifesto. Perspecta 54: Atopia. ↩

- Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist realism: Is there no alternative?. Zero Books. ↩

- Lokko, L. (2022). Biennale Architettura 2023: The Laboratory of the Future. https://www.labiennale.org/en/news/biennale-architettura-2023-laboratory-future ↩

- Le Guin, U. K. (2014). Ursula K Le Guin’s speech at National Book Awards: “Books aren’t just commodities”. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/nov/20/ursula-k-le-guin-national-book-awards-speech ↩