This article explores how play can expand design practices. Understanding playgrounds as spatio-temporal assemblages of objects, people, situations or phenomena that we can address and manipulate in a playful way, we propose the idea of understanding design, itself, as a playground. In response to the question “How can we think of design as a playground?”, this article presents an expanded notion of play and reflects on how it can serve as a foundation for rethinking spatial design.

1On Playgrounds

Playgrounds aren’t things we create as much as structures we discover. (…) Living playfully isn’t about you, it turns out. It’s about everything else, and what you manage to do with it. 1

Today, playgrounds are typically understood as self-contained children-friendly heterotopias interspersed in (although often not related with) the urban environment. Although standardized and regulated playgrounds are currently a seemingly unavoidable reality, both the idea of a space specifically designed for children to play and the term ‘playground’ were born at the end of the 19th century under the drive of social reform.2

The playground movement—initiated in the 1880s in the US (although strongly rooted in slightly earlier German proto-playground practices)3

—advocated for the need to include play in public policy, thus generating the first designed urban playgrounds. The spatial embodiment of these early playgrounds consisted mostly of two typologies that are the forebearers of current playgrounds: the school sandpit and the outdoor gymnasium (e.g., Marie Zakrzewska’s 1885 Boston Women’s Club sandgarten4

and the 1821 outdoor gymnasium at the Latin School in Salem5

). They both combine a well-meaning hygienist drive advocating for the children’s need to exercise outdoors to palliate the unwholesome consequences of working-class modes of life, as well as a more obscure program of social engineering designed to reinforce state power over citizens.

In the 1930s and especially in the post-war period the over-simplistic socio-cultural problematization and design resolution of these deterministic and monofunctional early playgrounds was criticized by progressive designers. For example, Aldo van Eyck who proposed a seamless relation between playgrounds and the surrounding cityscape (e.g., Bertelmanplein, Amsterdam, 1946)6

; Isamu Noguchi who explored open-ended landscape playgrounds (‘playscapes’, e.g., Play Mountain, 1934, although the first built example is Piedmont Park, Atlanta, 1976)7

; Carl Theodor Sørensen who spear-headed a hands-on, experientially-rich environment in detriment of usual considerations regarding safety and adult surveillance (‘byggleplads’ or ‘construction playground’, e.g., Emdrup, Copenhaguen, 1943)8

; or Marjorie Allen who introduced junk playgrounds turning the rubble of WWII into a stage to use play for healing war-wounds (‘adventure playground’, e.g., Paddington, London, 1946)9

. These early experiences—based in understanding playgrounds in continuity with the cityscape—led to very interesting critical approaches to playground design.10

Unfortunately, innovative and critical approaches to playground design, remain, to date, isolated initiatives in a sea of risk-averse, banal and reductive urban playgrounds, dominated by McDonald’s-inspired cookie-cutter playgrounds.11

There is a line of thought, represented by Tim Gill, that is highly critical of the risk-averse approach that shapes most contemporary playgrounds.12

Other voices, such as Palle Nielsen,13

go as far as radically negate the validity of so-called “playgrounds” inasmuch as play cannot be bounded to pre-defined spatial confines (e.g., fence), performative rituals (e.g., sliding down a slide) and regulated elements (e.g., standard swing set). According to this approach, there should be no areas expressly defined as playgrounds,14

rather the whole city should be playable.15

Furthermore, we may follow games scholar Ian Bogost in foregoing the playground in its conventional sense of bounded physical area expressly designed for children to play and, instead as “a place where play takes place, and play is a practice of manipulating the things you happen to find in a playground”.16

Playgrounds, then, are spatio-temporal assemblages of objects, people, situations or phenomena that we can address and manipulate in a playful way. Following this view, we propose the idea of understanding design, itself, as a playground.

2On Play in Design

Civilization (…) arises in and as play, and never leaves it. 17

The deep-seated reasons for the conventional nature of contemporary’s urban playgrounds are rooted in the way play is understood—as a menial childish activity. Indeed, in most cases play is seen in opposition to work, with all the moralistic implications this carries. Play is usually assumed to be, and even explicitly described, as a useless, unproductive activity. Play ranges between wasted time and mere entertainment, as opposed to serious work, a productive activity that generates society’s true value. Yet this is far from true. Critical theory has consistently construed play as a necessary condition for the generation of culture and as a crucial process in human cognitive development. Since the trailblazing work of Johan Huizinga,18

pioneering authors have definitively disconnected play and games from their traditional association with frivolous or inconsequential activity.19

Following the spirit of these authors (if not always their statements), we claim that play is so relevant that it should be conceived as a way to relate to the world, rather than a specific sub-set of “childish” activities that we can isolate and treat accordingly.

Other fundamental aspects notwithstanding, we are particularly interested in the generative value of play: play may be used as a way to transform reality. Although some authors state the contrary, i.e., that play and games “cannot found or produce anything”,20

we claim that playing is, precisely, one of the most powerful ways of doing just that.

We can understand play as addressing three basic themes: limits, self and chance. These refer, respectively, to the way we construe an understandable order of the world (how we establish physical, temporal and normative limits to define a specific subset of actionable reality in order to deal with it), the way we construe ourselves (how we construct our own selves in relation to others) and the way we construe the unobservable or hidden forces of reality (how we deal with asubjective agencies21

). Play, then, simultaneously addresses the objective, subjective, and asubjective realms. This threefold capacity of play to define limits, test and expand the self, and address chance makes it a perfect ally for all design-based disciplines, whose primary aim is to transform our world, imagining and projecting other realities. The relationship between play and design is a very strong one, and one worth exploring in a radical way. Indeed, thanks to their simultaneously regulated and exploratory nature, games and play can be harnessed to fuel the disruptive capacities of design.22

An expanded notion of play holds an incredible potential for design, leading us to the question: “How can we think of design as a playground?” We can summarize the contribution of play to design in three concepts that mirror the triad of play’s pursuits: constraints (facilitating an explorative use of factual or self-imposed constraints); engagement (prompting new types of engagement and authorship through dialogism); and chance (creatively embracing chance).

First, play is a way to creatively address problem-solving, using a pre-defined set of rules as opportunities rather than hindrances. Straining preconceived ideas and temporarily suspending accepted relationships with the milieu, play mobilizes a system of rules and voluntary constraints that prompt an exploratory attitude within the accepted limits. This hones strategic thinking and an active attention to the milieu, whether physical, social, cultural or relational.

Second, the dialogic nature of play 23

allows us to enact new modes of kinship and authorship, exploring other visions and other subjectivities, using role-play to temporarily inhabit another subject or negotiation to open up to other subjects, thus expanding subjective limitations and engaging in complex processes of subjectivation. In so doing, play generates choral works that are the result of rich interactions between different people, while maintaining a recognizable and communicable outcome. Play engenders polysemiotic situations, where personal discovery promotes a psychologically activated link to the environment and the people in it. Whether collaborative or oppositional, play opens up opportunities for moving beyond hardened subjectivities and fosters processes of creative subjectivation through role-playing, negotiation and dialogism.

Finally, play allows us to creatively respond to chance events. By allowing chance into the equation, game-based formats and playful practices prompt us to react creatively to unexpected and unplanned events, honing tactical thinking.24

The profound openness introduced by chance (wild cards, dice rolls, random dealing, chance scenarios) also lets us move beyond design’s conventionally planned briefs and scenarios, making it possible to simulate complex realities within the limited confines of the game, thus testing our abilities to respond to a radically unknown future, one that could not have been predicted from the outset.

Rather than solutions answering to a predefined brief, when using game-based formats and playful practices in design, the project’s results are strongly informed by an exploratory and open-ended design logic.Most importantly, playing lets us supersede design as representation and embrace design as simulation, which allows design to become performative rather than descriptive.

3Case Studies

The challenge, then, is to find ways to make interesting, complex play environments using the intricacies of critical thinking and to encourage designers to offer many possibilities in games, for a wide range of players, with a wide range of interests and social roles. We can manifest a different future. 25

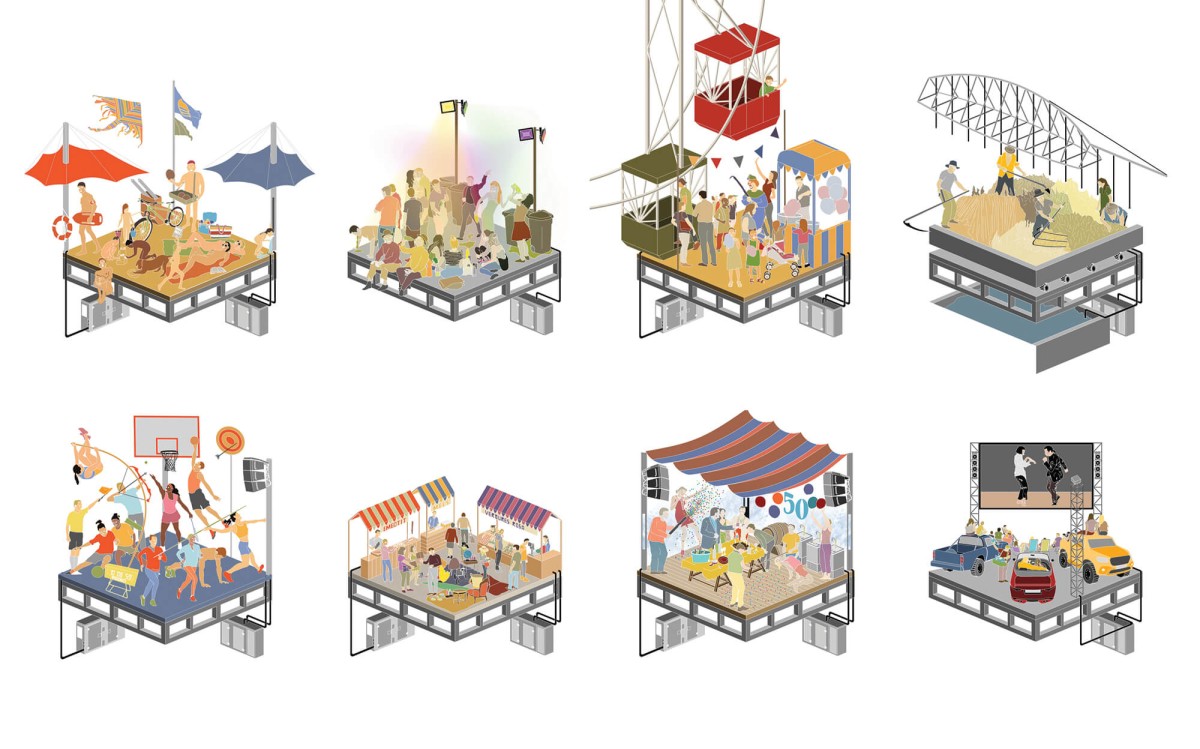

In this section, we discuss the case studies. These are intended to illustrate how incorporating game-based formats and playful practices into the design process can inform urban and architectural design, tying in with the three concepts described in the previous sections: constraints (facilitating an explorative use of factual or self-imposed constraints); engagement (prompting new types of engagement and authorship through dialogism); and chance (creatively embracing chance). It is relevant to clarify that we are not addressing game design per se. Further research incorporating a cross-disciplinary approach between spatial designers and game designers would no doubt prove highly fertile. El Núvol [The Cloud]: New Habitats—Re-Thinking Zona Franca proposes a board game format to meet the challenge of repurposing an industrial estate into a vibrant mixed-use neighbourhood, resulting in strategic design approaches coupled with highly specific typological proposals based on bottom-up architectural proliferating systems. Horizon 2080: A Game-based Design Workshop for Future Cities proposes a short scenario-writing seminar, based on four movements (chance, negotiation, dialogism, speculation) to engage all participants in exploring radical urban futures in order to prompt design challenges for the present. Civic Plugins: Microarchitectures for Superblock Community-Building uses a large-scale physical model and three decks of cards to playfully design micro-architectures and common spaces to foster collaboration and social cohesion.

For each of these three case studies, the following pages offer a description of the context, summary, research question, methodology, and, most relevantly for this paper, the game-based formats and playful practices explored. Although this article focuses on these three case studies, other contributions by the author on design and play provide an expanded review of design as playground (Elvira and Paez, 2019; Paez, 2022). The first publication presents Archispiel, an urban design format drawing on traditional war games and diplomacy games that combines strategic negotiation with the use of chance to produce unexpected effects (Fig. 01).26

, a seven-day intensive workshop directed by Roger Paez and Juan Elvira in July 2015. The workshop was organised by Q9 and hosted by COAIB to explore the architectural and urban impact of tourism in Majorca. The design team was comprised by Roger Paez, Juan Elvira and 13 students from architectural design and social sciences backgrounds. For more information, see Elvira and Paez 2019.] The second explores disruptive uses of serious games to generate and communicate radical urban visions, focusing on the design studio Barcelona Radical Landscapes (Fig. 02).27

Fig. 01: Partial result of Archispiel (2015).

Fig. 02: Partial result of Barcelona Radical Landcapes (2021), “Deus Ex

4El Núvol [The Cloud]: A Board Game to Rethink Barcelona’s Zona Franca

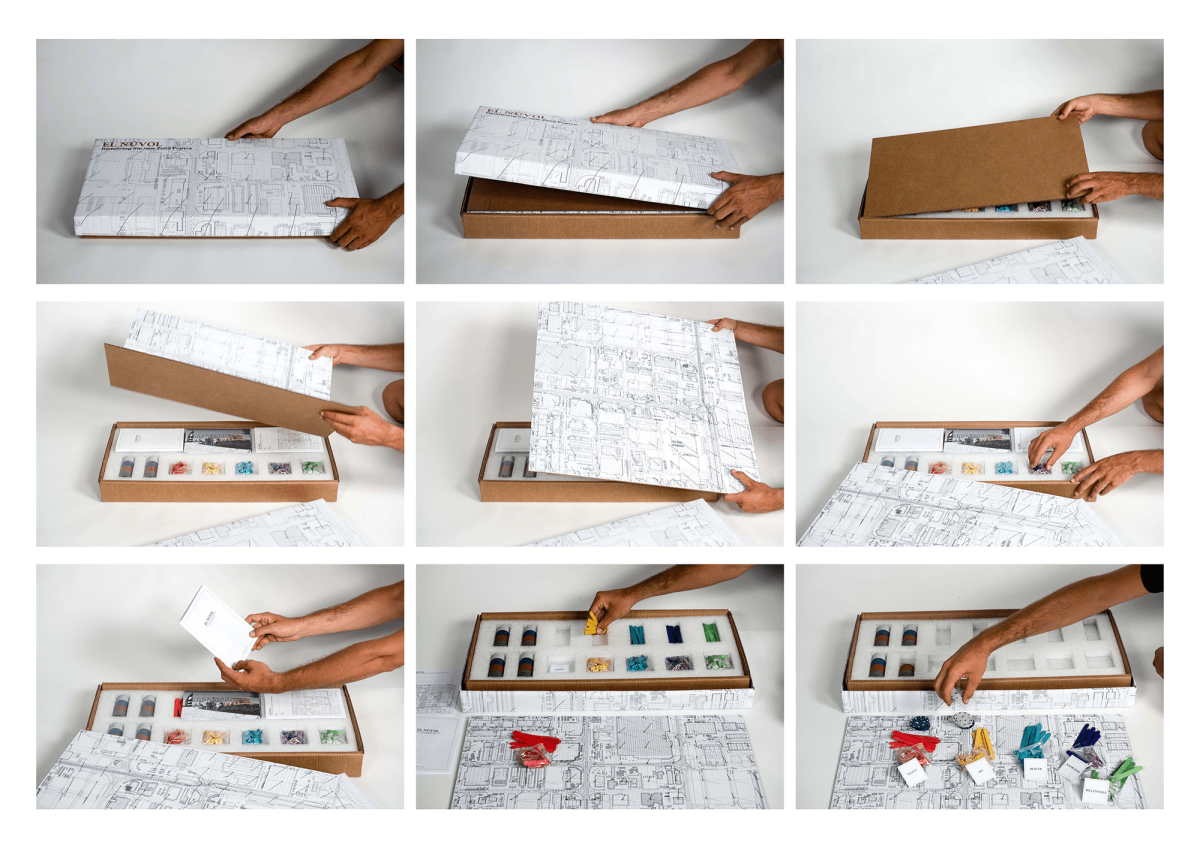

El Núvol (eN) [Catalan for ‘The Cloud’] was developed and tested in a series of four workshops organised during two academic years of the MIAD programme (ETSALS, Barcelona).28 The first workshop (June 2018, 4 weeks) was directed by Roger Paez and Jordi Mansilla, and the rest (December 2018, March 2019 and April 2019, 5 weeks in total) by Roger Paez. The design team was comprised by the abovementioned faculty and 13+12 Master’s students.29

5SUMMARY

eN uses a board game to address a complex urban question: how to progressively transform an industrial and logistics hub into a vibrant mixed-used neighbourhood, promoting creative interactions between education, business and production, using novel housing typologies as the core programme. The first stage centres on designing and building the prototype of a brand-new board game, the second stage involves playing the game multiple times, and in the third stage game processes and results are used to inform architectural, urban and service design proposals on multiple scales.

6RESEARCH QUESTION

Barcelona’s Zona Franca is a fully working urban structure, but it lacks programmatic complexity. eN explores a progressive transformation to gradually shift a logistical mono-culture toward a diverse ecology comparable to a compact, dense Mediterranean city. The investigation addresses three specific questions: progressive transformation of cities, adaptive reuse of buildings and designing proliferating systems of housing. In order to avoid drastic and sudden change, progressive transformation is used to explore the urban possibilities offered by a cross-pollination between the current productive landscape and the future social milieu. Adaptive reuse is embraced to promote hybridization of uses and building typologies that may take full advantage of the site’s conditions. Industrial structures help to re-envision housing models that go beyond traditional solutions and embrace exceptional potentialities. Not only the urbanscape is critically re-thought, but housing typologies and living models as well, introducing ideas such as housing as a service. The proposals incorporate proliferating systems of housing that grow according to their own internal logics while taking advantage of the specific opportunities found on the site. The resulting urban scenarios are not well-groomed urban utopias but exciting stochastic landscapes where design plays a cueing role rather than a regulating one.

7METHODOLOGY:

eN explored the rare opportunity of extending a student-based research work beyond the confines of one academic year. Besides providing further research opportunities, this is interesting as students react to the work of their peers and learn to opportunistically read the design possibilities of the work of their predecessors. During 2017-18 the board game was conceived, designed, prototyped and explored, using the game to generate a choral urban design proposal that became a flexible framework for 2018-19 design workshops. During 2018-19, three different design workshops used the board game to suggest, cue and prompt design decisions. During the first academic year, the design outputs informed by the game were limited to city-scale visions and strategies, and the design proposals remained at an urban scale (i.e., overall narrative, full-site negotiated urban strategy axonometry, suggested urbanscapes vignettes). During the second year, the scale was narrowed down to built structures and housing typologies, and the level of detail of the design proposals was duly increased (i.e., multiple site identification, proliferation of urban strategies in 5, 10 and 20 years, overall 5,000 sqm design proposal, detailed novel housing typology studies, housing as service proposals).

8GAME-BASED FORMAT AND PLAYFUL PRACTICES:

eN uses a board game format to playfully address potential urban futures and actively inform their design. The game experiences and results are seamlessly incorporated into a number of decision-making processes, such as defining the design brief, fostering team-building, informing negotiation with other stakeholders, identifying design opportunities and proactively suggesting potential design solutions. Not only do the results of the game provide design insights, but the very experience of playing is relevant, as it generates inter-subjective relationships, reinforces teamwork and, through role-play, allows designers to experience, first-hand, the needs, interests and desires of others.

The game includes a game board, game pieces, and an instruction booklet. The board is a 121-square gridded board made up of nine superimposed maps of the site. Each layer of the board maps a particular aspect of the site, thus construing a specific vision of its characteristics and opportunities.30

The game pieces are tokens, cards and a six-faced die. The tokens identify investment or cost (money tokens), property (plots for sale), and actions, which may be built structures (blocks) or other-than-physical relationships (long connections, short connections, pegs). There are also two decks of cards: mission cards, which define the main objectives of each team, and blank cards for each team to fill in their strategies to achieve their given mission (Fig. 03).

Fig. 03: el Núvol [The Cloud] (2018). Board game.

The players are given roles according to the real stakeholders with vested interests on the site. The stakeholders may be defined as existing interest groups,31

or as content-oriented poles derived from the general brief.32

Whichever system is used, players are asked to set aside prejudices and focus on the logic of the agents they represent.33

There is always one player who will act as the Bank and will manage non-occupied plots, actions and connections.

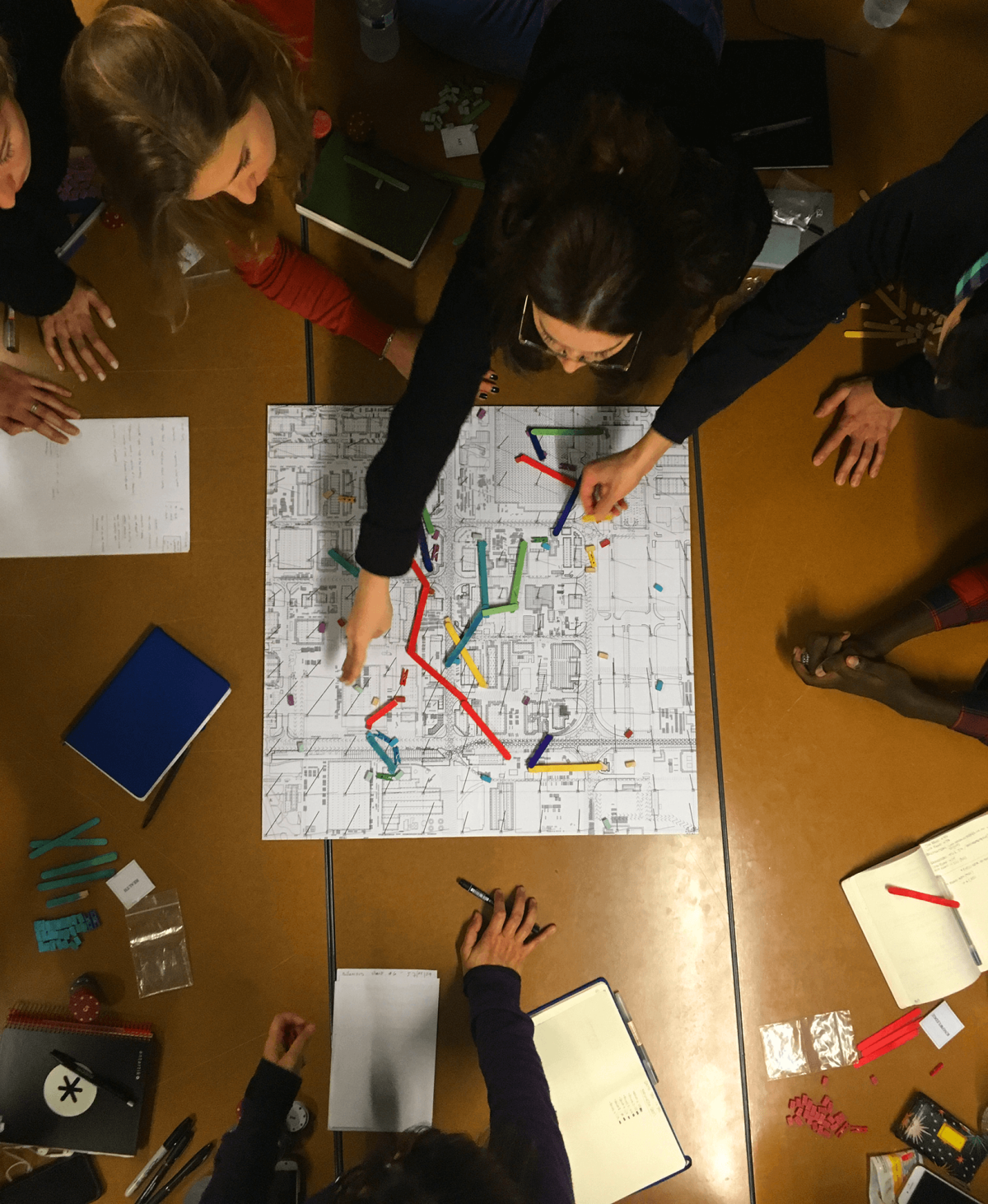

To play the game, each team starts with the same amount of action blocks and money tokens. Each team gets a mission card and two blank cards where they will fill in specific strategies to achieve their mission. As the game progresses, tactical moves are made. Players roll the dice to determine who starts (highest roll) and then play clockwise. For the first five rounds, each team throws a block onto the board and takes ownership of the plots where the blocks land. After each team has acquired the first five plots, a round of negotiation starts. Each team decides whether they want to sell any of their plots, the plots to be sold are put up for auction and the highest bidder wins. The buying team gets the plot, the selling team gets the money (Fig. 04).

Fig. 04: el Núvol [The Cloud] (2018). Playing the game.

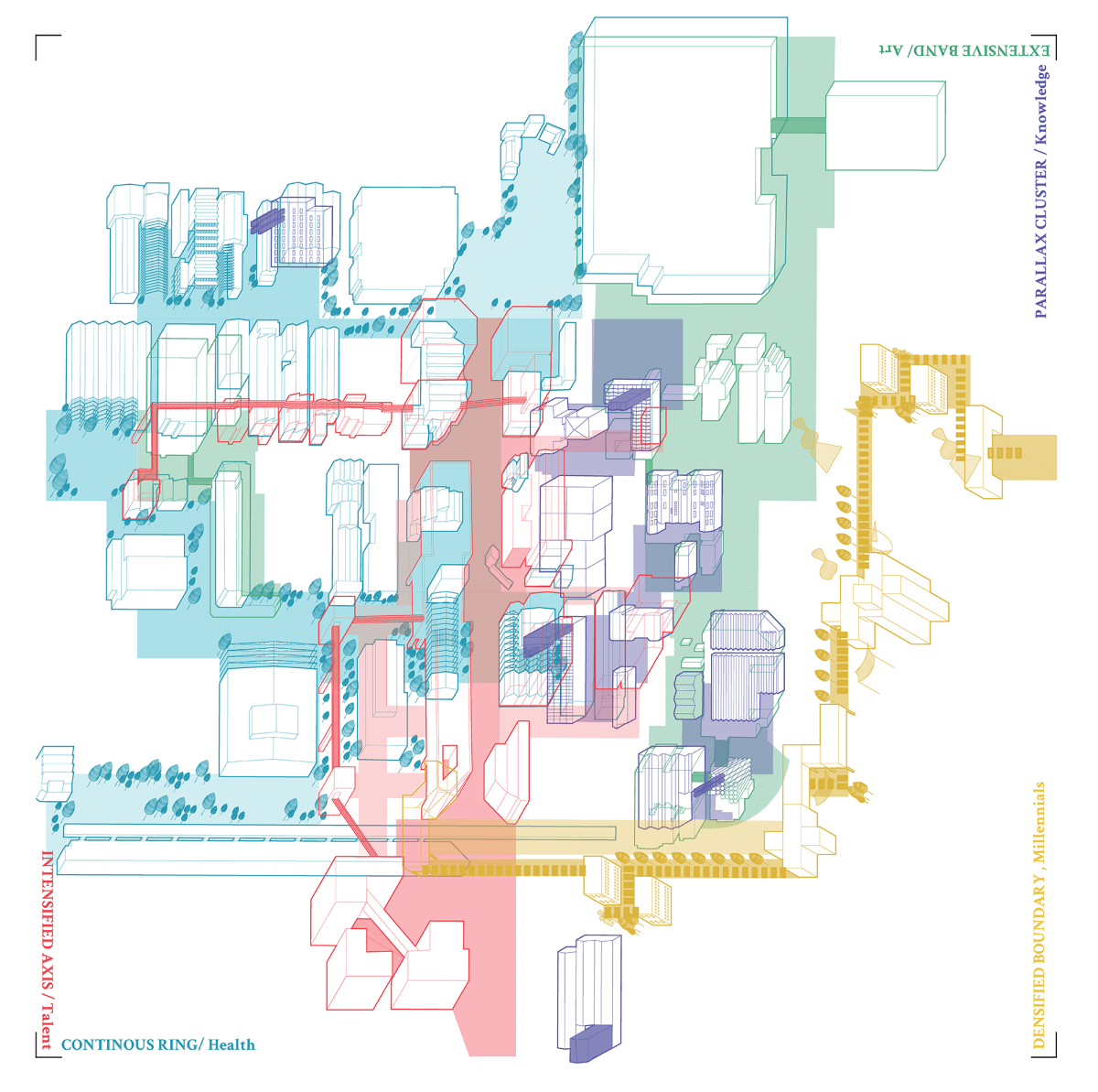

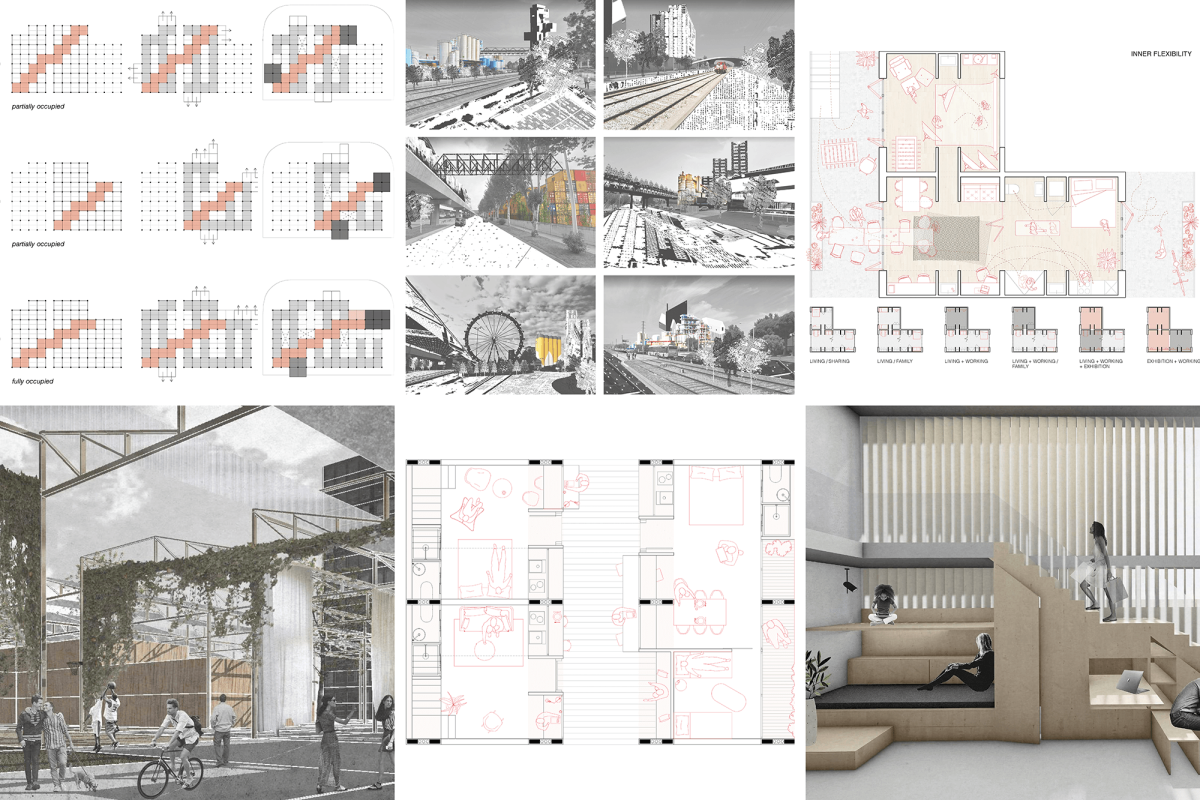

The results of the game are put into a productive relationship with three design approaches that are developed in parallel to playing the game: defining desirable urban narratives (large scale)(Fig. 05),

Fig. 05: el Núvol [The Cloud] (2018). Game results, urban strategies.

defining novel housing typologies (small scale) and defining systems with internal proliferation logics within the site (medium scale) (Fig. 06).

Fig. 06: el Núvol [The Cloud] (2019). Game results, proliferation systems and housing typologies.

The game does not automatically determine design solutions, rather it is used as a mediation system between different designers to relate to one another and as a way to prompt complex decision-making processes so that designers may establish a constructive relationship with a set of constraints—given by the game’s setup, chosen by the designers during the game’s development, or randomly introduced by chance. eN allows for integrating different and unrelated research and design avenues (such as desirable urban visions and new housing typologies) in an engaging exercise of critical thinking, peer-to-peer negotiation and a creative response to chance events.

9Horizon 2080: A Game-based Design Workshop for Future Cities

Horizon 2080 (H2080) was a one-day scenario-writing workshop directed by Roger Paez and Manuela Valtchanova on June 13, 2019. It was part of the Cities as Playgrounds interdisciplinary workshop34 organised by RMIT Europe and integrated in Barcelona Design Week 2019.35 The design team was comprised of Roger Paez, Manuela Valtchanova and 12 other international interdisciplinary researchers including game designers, play theorists, ethnographers, sociologists, philosophers, architects and designers.36

10SUMMARY:

H2080 was a test run of Speculative Urban Futures (SUF) COST Action,37 aiming to face future urban emergencies through speculative design approaches in the present. Embracing the increasing ambiguity and complexity of society’s trend toward global urbanisation, SUF proposes engaging today’s uncertainty in order to enable new desirable futures. Working with design tools such as storytelling, scenario writing and game formats, it aims to generate a cross-disciplinary speculative environment, where multiple visualisations of urban futures are construed through factual knowledge, imagination and chance dynamics. The project’s main objective is to foster the definition of new design challenges based on multiple fictional scenarios. Those challenges are intended to be further developed as new design briefs for academic, professional and research practices. In a nutshell, SUF is aimed at exploring future urban scenarios to prompt design challenges for the present.

11RESEARCH QUESTION

Due to the massive demographic growth and the concentration of the world’s population in cities, rethinking urban habitats is and will remain one of the main issues humanity and the planet need to address. Most current projections forecast a sustained global population growth and an even more dramatic concentration of people in cities.38 ‘Horizon 2080’ is the 60-year time frame that will likely consolidate the trend toward global urbanisation, during which we will need to successfully address global issues that will otherwise endanger the sustainability of our way of life and indeed our very lives. Although myriad issues are entangled with the way cities are and will be, five thematic fields may be identified that will most certainly maintain their relevance in the coming decades: demography, society, mobility, environment and post-humanism. These topics articulate wicked problems that cannot be resolved definitively but need to be addressed if we are to survive as a species.

12METHODOLOGY:

One way to articulate a productive relationship between city and design is to use playful practices and game-based formats, fostering speculation in order to visualise possible, plausible, probable and desirable futures.[See Dunne and Raby 2013, 3-6.^] H2080 is an introductory effort aimed at doing precisely that. H2080 presents, discusses and builds on recent examples of game-based design formats as methodologies to foster new urban projects and visions. Game formats allow us to introduce chance and negotiation as key drivers in the design-making process, thereby obstructing conventional top-down master planning logics and introducing other ways to approach the design of future urban habitats. The two-hour workshop was organised in two parts: a short presentation of recent game-based urban design experiences and a scenario-writing seminar, based on four movements (chance, negotiation, dialogism, speculation), to engage all participants in fostering urban design through play. Participants used game mechanics of future “facts” to imagine and write speculative future fictions about the world in 2080.39 Participants were then guided to produce a design brief for the present, posited on the certainty of those futures occurring.

13Game-based format and playful practices:

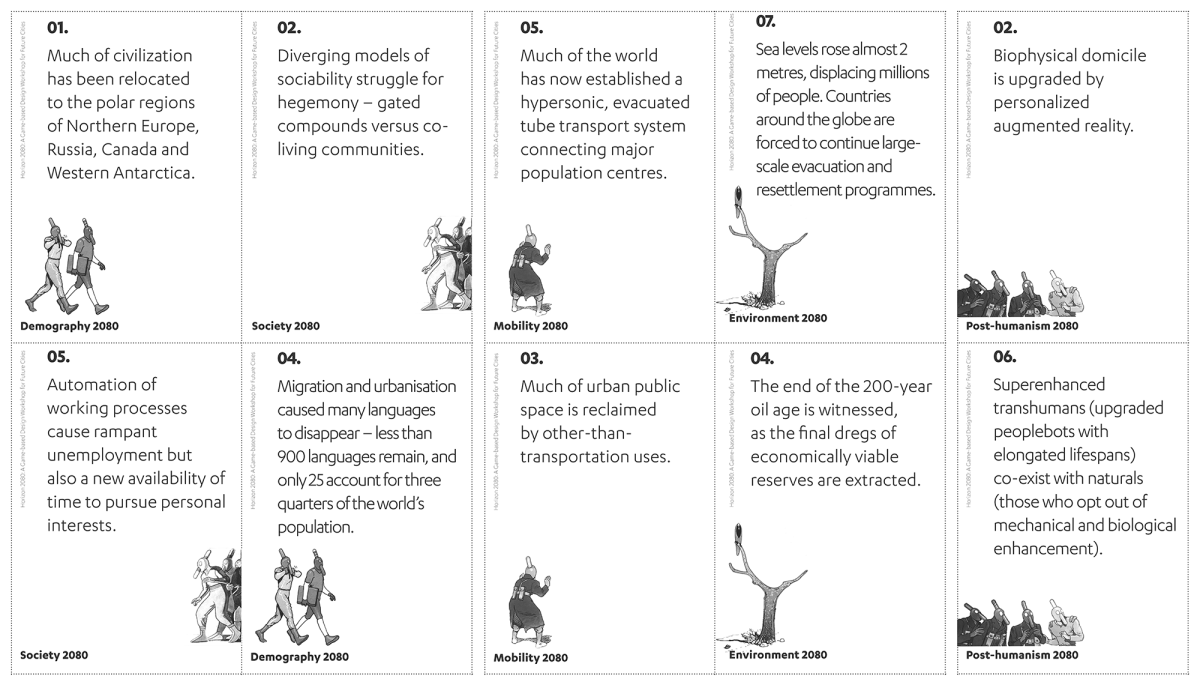

H2080’s game-based format is made up of seven steps. The initial card deck is comprised of 60 cards, 12 for each thematic field (demography, society, mobility, environment and post-humanism). Each card includes a 2080 “fact” in the form of a foreseen statement (Fig. 07).40 There are four teams of two or three people.

Fig. 07: Horizon 2080 (2019). What-if cards, detail.

First, half of the players (teams 1 and 2) are randomly dealt a set of 10 cards (two per thematic field). They study their cards and choose five of the 10, based on their interests and potential cross-pollination between the dealt cards. The same is done for the other half of the players (teams 3 and 4), so that each half will end up with five chosen cards.

Second, a team debate ensues, prompted by the five chosen cards.41

Each team will internally discuss the implications of the future facts presented in their cards and sketch probable or desirable relationships between them.

Third, each team keeps only two of their cards. Half of the teams (teams 1 and 3) choose their final cards through negotiation among the team members, while the other half (teams 2 and 4) by blind chance. This lets us look at the differences between the narratives prompted through choices based on reflection and those derived from choices based on chance.

Fourth, each member of the team individually writes a one-page scenario describing a 2080 urban condition based on the cards. The scenario should factually describe a future situation assuming that the facts from the two final cards actually come to pass (Fig. 08).

Fig. 08: Horizon 2080 (2019). Playing the game.

Fifth, all players gather in a situation room format. All scenarios are read, an open debate ensues, and game masters draw initial conclusions from the discussion—both in the form of statements and questions.

Sixth, game masters define new two-person teams based on the similarities or resonances of each individual scenario. These new teams discuss and propose design brief proposals for the present based upon the certainty of the futures described in their scenarios. The design briefs are written in such a way that they may be immediately proposed to architecture and design schools and included in their syllabi to become food for thought for students, faculty and researchers.

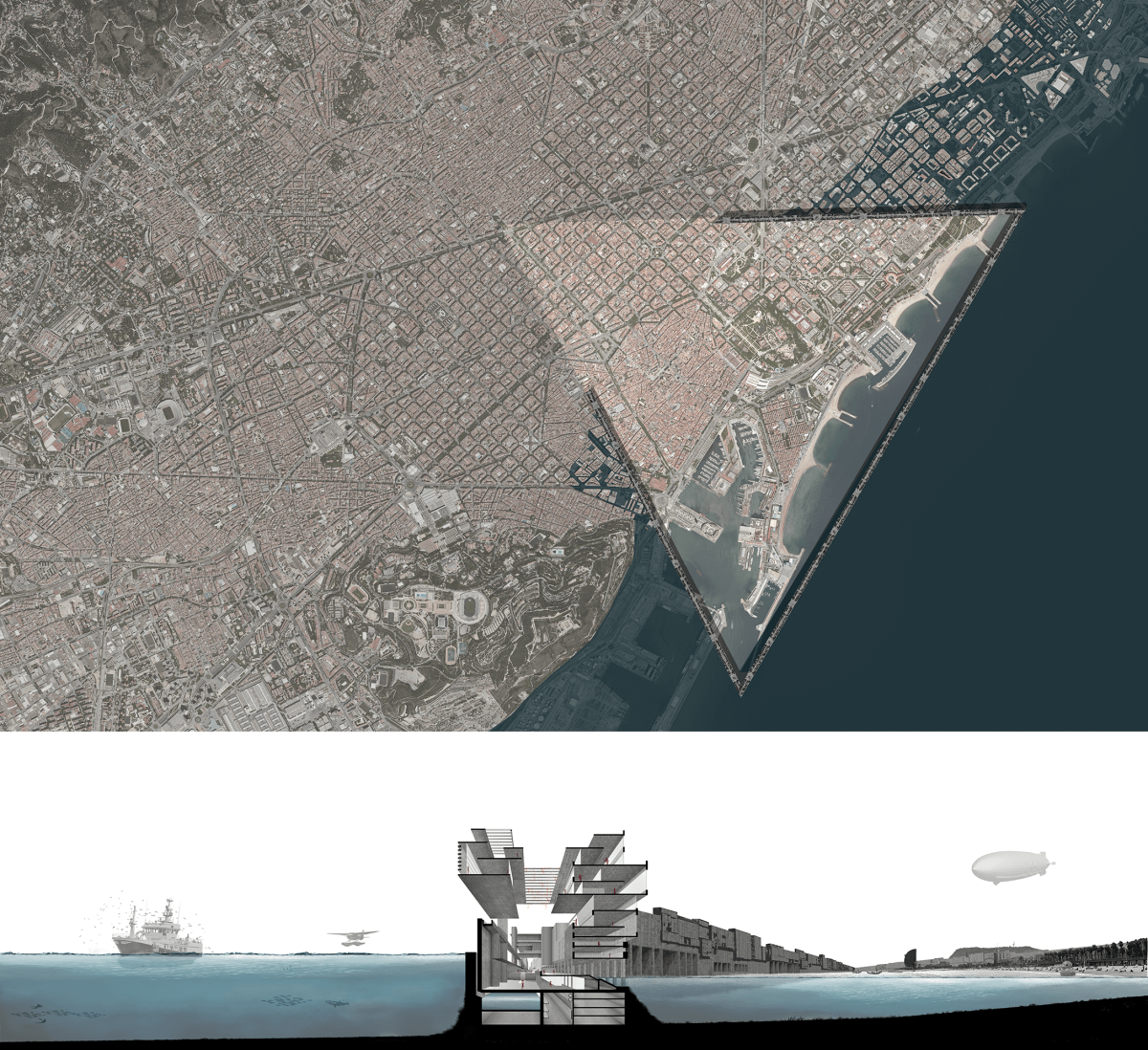

Lastly, the seventh step involves sharing all the design briefs and drawing the conclusions from the game, including uncovering specific opportunities for moving forward with the effort, such as identifying potential stakeholders and educational hosts for each of the design briefs. Some of the workshop results were experimentally used as design briefs for undergraduate42

(Fig. 09) and postgraduate43

design studios (Fig. 10) in different academic institutions.

Fig. 09: Horizon 2080 (2019). Game results, ‘sea level rise and new medievalism’ scenario used as design brief for Barcelona Radical Landscapes (2021), “Sea Wall”, Carles Gesa, Martin Nicholls, Carlos González.

Fig. 10: Horizon 2080 (2019). Game results, ‘phygital spaces and augmented reality’ scenario used as design briefs for Infrastructures for Public Space Interaction (2020), “Zentropy: Ground Zero of Digital Wellbeing”, “AR-scape: Not Mine, or Is It?” and “Tales from the Loop: Genius Loci Meets Global Consciousness”, Tiago Rosado.

14Civic Plugins: Microarchitectures for Superblock Community-Building

Civic Plugins (CP) was developed in a three-week workshop organised in December 2019-January 2020. It was a collaborative effort between MEATS Elisava (Barcelona) 44 and Balwant Sheth School of Architecture (Mumbai) 45 , directed by Roger Paez, Toni Montes, Atrey Chhaya and Bhavleen Kaur. The design team was comprised by the abovementioned faculty and 27 Master’s students.46

15Summary:

CP aimed to design a prototypical intervention using micro-architectures as civic infrastructure to articulate informal, organic and self-managed programs to foster collaboration and social cohesion. In order to address this question, the main goal of the workshop was to identify informal, organic and self-managed collaborative logics among residents of two neighbourhoods in the city of Mumbai (Khotachi Wadi [Girgaon] and Dattatreya Chawl [Charni Road]) and to explore spaces of opportunity in the city of Barcelona, where similar logics could be implemented to generate common spaces and effectively improve social cohesion (El Raval [Ciutat Vella]). Working through game-based design practices on a site that epitomizes El Raval’s character as a test bed, these solutions could be applied throughout the district, and indeed in any compact city milieu, outlining a new meaning for the superblock model.47 Rather than public or private spaces, CP specifically addressed common spaces, positing them as key to community-building within the framework of the contemporary revision of the compact, dense and complex city as the most environmentally and socially sustainable urban model.

16Research question:

CP’s research question is how to foster common spaces in contemporary cities. Architectural design has paid a lot of attention to both shared and public spaces, i.e., the individual/familial cell which makes up most of the urban fabric, and the public space system which acts as the connective tissue of cities and embodies its narrative. But for several reasons, (Western) cities have lost most of their common spaces. The contemporary polarization between highly private spaces (a home is a castle) and administration-managed public spaces has resulted in a loss of complexity in the way citizens interact. That has implications in the physical makeup of the city, such as the loss of in-between spaces and urban thresholds, but it also affects the relational setup, oversimplifying our relations with others and severely curbing the sense of belonging to a community-in-place: either we are isolated in our safe and over connected capsules or we are exposed in public spaces managed by the administration. An intermediate level of common spaces, shared and cared for collectively, would help foster community-building processes in an environmentally and socially sustainable way.

17Methodology:

The workshop was a three-week collaborative program. During the first two weeks, the Mumbai team identified informal, organic and self-managed collaborative logics among residents of two neighbourhood communities in the city of Mumbai, while the Barcelona team explored prototypical spaces of opportunity in the El Raval district where spaces promoting community life could be implemented. Basically, Mumbai provided programmatic exploration, while Barcelona provided the socio-spatial framework. In the third week, both teams worked together to build a 1:20 physical model of a site that epitomized El Raval’s character and used it as a test bed for microarchitectures that foster community-building through the generation of common spaces, i.e., spaces in between private dwellings and public space, which provide pragmatic solutions to questions of accessibility, flexibility, appropriability, temporary uses or storage while acting as relational hubs. Given their prototypical condition, these solutions could be applied throughout the district, defining a new meaning for the superblock model. Moreover, their replicability is not limited to El Raval or to Barcelona, but these “community plugins” have the potential to be applied in any compact city, addressing practical problems associated with upgrading the existing urban fabric and adding value to complex city environments.

18Game-based format and playful practices:

The workshop included two main game-based formats and playful practices: initially, a chance and negotiation stage using purpose-made cards; and then, a playful hands-on approach to direct model-building, using a large 1:20 physical model of the site.

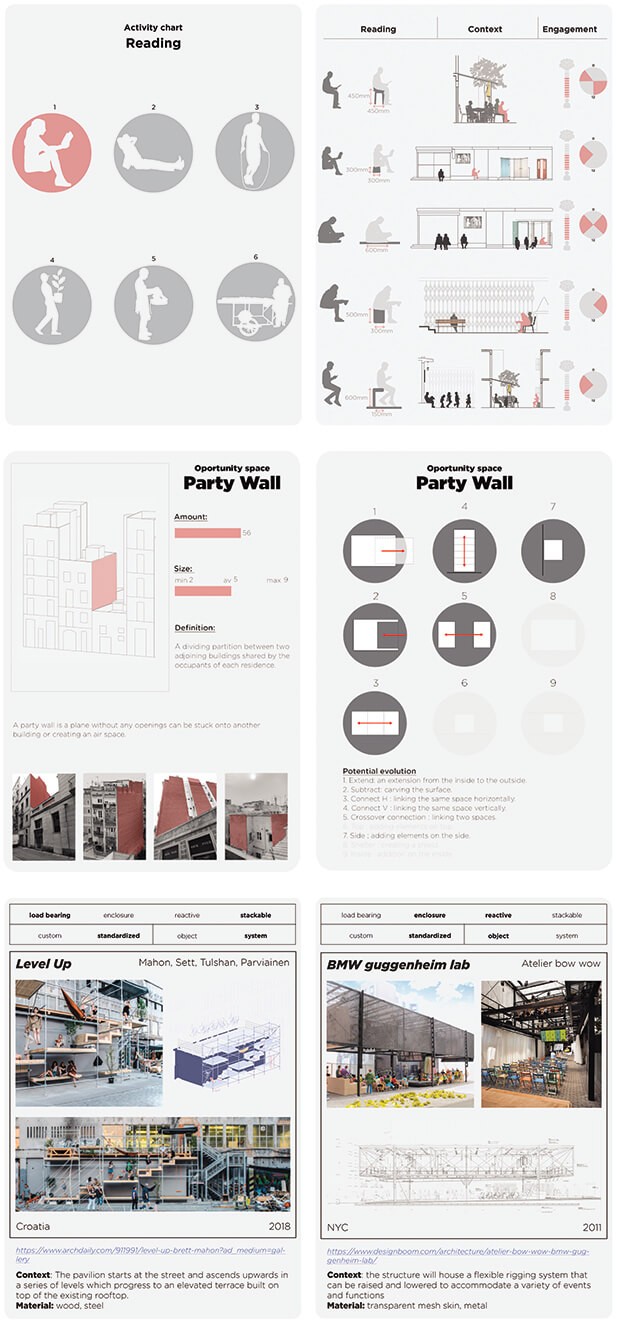

Three decks of card swere designed as a direct result of the initial research, including Action, Space and Reference cards (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11: Community Plugins (2020). Three card sets, detail.

Action cards summarized the results of the Mumbai team’s research on the specific ways in which Khotachi Wadi and Dattatreya Chawl inhabitants have appropriated their milieu creatively and generated in-between zones, thresholds and common spaces to address day-to-day issues such as informal or temporary spaces to work, store, wash, cook, play, or pray. The actions studied included gardening, storing, playing, reading, washing, drying, cooking, exchanging, sleeping, hosting and resting. Each Action card identified the different bodily positions and minimum spaces required, the different contexts in which the action took place, and the different amount of people involved at different times of day and night.

Space cards summarized the results of the Barcelona team’s research on the spaces of opportunity found in El Raval. These are the spaces that could be filled with the actions identified in the Action cards. The spaces of opportunity identified were rooftops, party walls, galleries, courtyards, shafts and airspace. The Space cards were complemented by a collection of maps that identified the recurrence of each of these opportunity spaces within the El Raval neighbourhood, thus allowing the players-designers to foresee the replicability of their designs beyond the site.

Finally, a deck of 20+ Reference cards was designed to provide background inspiration. The references included a formatted collection of flexible and upgradable dry-construction micro-architectures. Each card provided basic information on a built design plus a three-way taxonomy identifying formal, technical and performative aspects.

The design process of CP begins by dealing one Action card, two Space cards and four Construction cards to each team of two or three people. During a short period, each team proposes four design briefs reacting to some of the possible combinations of the dealt cards. During the third phase, each team publicly presents their briefs. They are debated and voted, retaining only the two briefs that receive the most votes. The fourth phase has each team quickly explore the chosen briefs in a rough working model, directly on the site model. This generates the need to negotiate between teams as they all work simultaneously on the site’s model, and their respective proposals enter into a creative friction that needs to be addressed. The fifth phase is, again, an open debate, in which each team pitches their two proposals to the whole group. Following a public debate, strategic decisions are taken, e.g., coordination between teams to achieve a specific common goal, fine-tuning design proposals so as not to repeat similar solutions, or suggestions of new proposals to connect or relate two or more proposals and generate synergies (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12: Community Plugins (2020). Playing the game.

The sixth phase implies all teams working separately, directly producing physical models that graft onto the physical site model (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13: Community Plugins (2020). Game results, physical model.

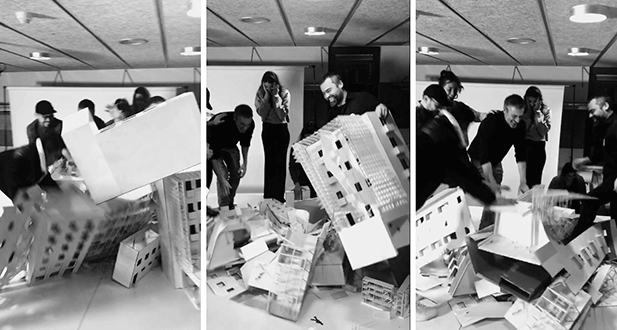

Because they work on the same model, teams necessarily work in relation to one another, and they keep reacting to their peers’ proposals in real time. In this way, the fifth-phase proposals keep evolving, sometimes merging together, sometimes further differentiating, sometimes being dropped altogether. The seventh and final phase is an open debate around the physical model, exploring all the relevant unexpected situations that arose thanks to the game format and playful approach to design. The results are interpreted by the whole group, rather than merely described, as the interactions between each team’s proposals are, by this stage, so strong that it becomes impossible (and unnecessary) to claim authorship of specific parts of the group project. As a cathartic celebratory act, the model is collectively destroyed, and the video of its destruction is a significant part of the project’s output (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14: Community Plugins (2020). Game results, destruction of the model.

19CONCLUSIONS

How do I act constructively with others in the indeterminate process of city-making? And how can I critically reflect upon this process while being constantly engaged in it? 48

As the case studies have shown, the relationship between design and play is a very rich one. Not only can we posit urban milieux as playgrounds, broadening conventional notions of play to include socially enriching civic engagement, but we can also, and indeed should, posit play itself as a way to critically design cities, using play’s capacities to expand conventional design approaches. As developed earlier, understanding design as playground is based in facilitating an explorative use of factual or self-imposed constraints, prompting new types of engagement and authorship through dialogism and creatively embracing chance.

With regards to constraints, El Núvol has all the trappings of a board game, including a gameboard, a system of tokens and pieces that protocolise the site and its stakeholders, and a strict set of rules which players have to follow while creatively advancing their own agendas. Horizon 2080’s what-if cards are based on a suspension of disbelief appropriate to speculative scenario writing. Civic Plugins explores both technical constraints (designing only through a physical model), temporal constraints (5 days) and programmatic constraints (proposing design briefs based on the combination of action, spatial and reference cards) in order to facilitate participants’ engagement during the limited amount of time allotted.

With regards to dialogism, El Núvol relies on role play (each player represents a specific stakeholder in the urban ecology) and negotiation (both open and covert) supported by a setup that prompts collaborative results which could never have been achieved otherwise. Horizon 2080’s system puts players in the position of having to tell stories to other participants’ in order to pursue their own agendas and to form new teams based on their respective narratives—personal memories and imagery are shared and discussed to achieve a dialogic conclusion that informs the design proposal. Civic Plugins uses prototyping to generate close-knit collaboration and to produce a highly cohesive result, authored by a team of people who had never met before.

With regards to chance, El Núvol incorporates chance through the initial block-throw, which defines the starting position of each team, and through wild cards and successive dice rolls that (may) change the outcomes of proposed initiatives. Horizon 2080 explores the different narratives generated by negotiation and chance, as some teams choose their what-if cards randomly, while others do so through debate and compromise. Civic Plugins’ uses randomly dealt cards to generate new and unexpected narratives, and participants are asked to tactically react to serendipitous events provoked by their peer’s developing proposals, resulting in a virtuous circle of feedback.

To conclude, these case studies enact a lively debate on authorship, critically exploring what it means to design today. Currently, there is a widespread mistrust of design as a significant agent of change. This is strongly rooted in the dominant idea of authorship in design (with its methodologically simplistic and ethically dubious implications): the designer as creator. 49

As this paper has hopefully shown, a radically exploratory approach to design as playground has a huge transformative potential, and rethinking authorship in design is one of its most obvious outcomes. Through a specific definition of constraints, designers can creatively organise and relate a sub-set of reality and turn it into a laboratory to explore specific questions, explicitly addressing the setup of the game as a crucial design question. Through role-play, designers can rewire intrasubjective responses and challenge dominant forms of subjectivation. Through negotiation, designers may explore new modes of intersubjectivity, which problematize post-Romantic authorship centred on an autarkic subject. Moreover, through the incorporation of chance, designers articulate a different relationship between design intent and effect, dismantling hard control and top-down design approaches and inviting non-human, asubjective agency.

Understanding design as playground, design authorship and design itself can be reinvented. Coupling pragmatic efficacy with visionary criticality, combining its role as solution provider and as a problematising practice, design can further its relevance as a practice that simultaneously contributes to proposing solutions and posing questions that help address significant societal, technical and cultural issues.

20Bibliography

• Alfrink, Kars. (2015). “The Gameful City”. The gameful world: approaches, issues, applications. Eds. Steffen P. Walz and Sebastian Deterding. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

• Allen, Stan. (2000). “Mapping the Unmappable: On Notation”. Practice: Architecture, Technique and Representation (pp. 31-45). London: Routledge.

• Bakhtin, Mikhail. (1981). “Discourse in the Novel”. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

• Bang Larsen, Lars. (2010). Palle Nielsen. El model. Un model per a una societat qualitativa. Barcelona: MACBA.

• BCNEcologia. (2019 October). Charter for the Ecosystemic Planning of Cities and Metropolises. http://www.cartaurbanismoecosistemico.com/index2eng.html

• Bogost, Ian. (2016). Play Anything: The Pleasure of Limits, the Uses of Boredom, and the Secret of Games. New York: Basic Books.

• Borden, Iain. (2007). “Tactics for a Playful City”. Space Time Play: computer games, architecture and urbanism: the next level. Eds. Friedrich Von Borries, Steffen P. Walz and Matthias Boettger. Boston, MA: Birkhauser.

• Burkhalter, Gabriella, ed. (2018). The Playground Project. Zürich: JRP-Ringier.

• Caillois, Roger. (1967). Les jeux et les hommes: la masque et le vertige. Paris: Gallimard.

• Caillois, Roger. (2001). Man, Play, and Games. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

• Dell, Christopher. (2019). The Improvisation of Space. Berlin: Jovis.

• Dickason, Jerry G.. (1983). “The origin of the playground: The role of the Boston women's clubs, 1885–1890”. Leisure Sciences, 6:1, 83-98.

• Elvira, Juan. (2005). “Control Remot / Remote Control”. Quaderns d’arquitectura i urbanisme 247, 84-95.

• Elvira, Juan, and Roger Paez. (2019). “Design Through Play: The Archispiel Experience”. VII Jornadas sobre Innovación Docente en Arquitectura (JIDA'19). Barcelona: UPC IDP, GILDA.

• Flanagan, Mary. (2009). Critical Play: Radical Game Design. Cambridge, MA.: The MIT Press.

• Frost, Joe L. (2010). A History of Children’s Play and Play Environments: Toward a Contemporary Child Saving Movement. New York: Routledge.

• Gill, Tim. (2007). No Fear: Growing up in a risk averse society. London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

• Huizinga, Johan. (1948). Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

• Kozlovsky, Roy. (2007). “Adventure Playgrounds and Postwar Reconstruction”. Designing Modern Childhoods: History, Space, and the Material Culture of Children; An International Reader. Eds. Marta Gutman and Ning de Coninck-Smith. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

• De Lange, Michiel. (2015). “The Playful City: Using Play and Games to Foster Citizen Participation”. Social Technologies and Collective Intelligence. Ed. Aelita Skaržauskienė. Vilnius: Mykolas Romeris University.

• Larrivee, Shaina D.. (2011). “Playscapes: Isamu Noguchi's Designs for Play”. Public Art Dialogue, 1:01, 53-80.

• McCarter, Robert. (2015). Aldo van Eyck. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

• McGuire, Leslie. (2004, September 1). Isamu Noguchi’s Playground Designs. Landscape Architect. https://landscapearchitect.com/landscape-articles/isamu-noguchis-playground-designs

• O’Connor, Amanda Rae, and James F. Palmer. (2002). “Skrammellegepladsen: Denmark's first adventure play area”. Proceedings of the 2002 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium (pp. 79-85), Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

• Ortega, Lluís. (2017). The Total Designer: Authorship in Architecture in the Postdigital Age. New York: Actar.

• Paez, Roger. (2019). Operative Mapping: Maps as Design Tools. New York: Actar.

• Paez, Roger (2022). “Game-based Practices for Radical Urban Visions”. Handbook of Research on Promoting Economic and Social • Development Through Serious Games (pp. 429-523). Eds. Oscar Bernardes and Vanessa Amorim. Hershey, PA: IGI Global Engineering Science Reference. DOI: 10.4018/978-1-7998-9732-3.ch022

• Paez, Roger and Manuela Valtchanova. (2021). “Harnessing Conflict: Antagonism and Spatiotemporal Design Practices”, Temes de Disseny, 37 Invisible Conflicts: The New Terrain of Bodies, Infrastructures and Communication, 182-213. DOI: 10.46467/TdD37.2021.182-213

• Piaget, Jean. (1962). Play, Dreams and Imitation in Childhood. New York: Norton.

• Sennett, Richard. (2013) Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

• Solomon, Susan G. (2005). American Playgrounds: Revitalizing Community Space. Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England.

• Stevens, Quentin. (2007). The Ludic City: Exploring the potential of public spaces. New York: Routledge.

• United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2017). World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, Key Findings and Advance

• Tables. Working Paper No. ESA/P/WP/248. New York: United Nations.

• van Westrenen, Francien. (2011). “Urbanism Game”. Game Urbanism: Manual for Cultural Spatial Planning. Ed. Hans Venhuizen. Amsterdam: Valiz.

• Vygotsky, Lev S. (2016). “Play and Its Role in the Mental Development of the Child”, International Research in Early Childhood Education Vol. 7, No. 2.

• Watershed. (2014). Playable City. https://www.playablecity.com/

• Wassong, Stephan. (2008). “The German Influence on the Development of the US Playground Movement”. Sport in History, 28:2, 313-328.

- Bogost 2016, 25-26. ↩

- For an extensive history of children’s play and play environments, see Frost 2010. ↩

- Wassong 2008. ↩

- Dickason 1983. ↩

- Frost 2010, 177. ↩

- McCarter 2015, 39ff. ↩

- Larrivee 2011. ↩

- O’Connor and Palmer 2002. ↩

- Kozlovsy 2007. ↩

- See, for instance, the work of Joseph Brown, Riccardo Dalisi, Richard Dattner, M. Paul Friedberg, Group Ludic, Egon Møller-Nielsen, Mitsuru Senda, Pierre Székely or Alfred Trachsel in Burkhalter 2018. ↩

- “The American playground is dominated by a McDonald’s model”. Solomon 2005, 82. ↩

- “society needs to embrace a philosophy of resilience: an affirmation of the value of children’s ability to recover and learn from adverse outcomes”, Gill 2007, 82. ↩

- See, for instance, two of Palle Nielsen’s “playgrounds”: The Model – A Model for a Qualitative Society (1968) and The Children’s Peace Corner (2009). “(Nielsen does) not to conceive of play as being derived from something else (…) Instead play is an independently becoming ontology of a future that should not be repressed”, Bang Larsen 2010, 80. ↩

- Isamu Noguchi already pointed in that direction when he proposed to think in terms of playscapes rather than playgrounds: “I later came to feel that children should not be restricted to fenced-in concrete play areas, and that some parks (…) should become 'play gardens'.” McGuire 2004, n.p.. ↩

- This is not the place to have an extended discussion on the issue of the explicit connections between urban life and playfulness. Suffice it to say that this general concept is currently being explored by different initiatives an under different epithets, such as “playable city” (Watershed 2014) “playful city” (de Lange 2015),“gameful city”(Alfrink 2015), “ludic city” (Stevens 2007), “game urbanism”, (vanWestrenen 2011) or “playful city” (Borden 2007). ↩

- Bogost 2016, 20. See Bogost 2016, 19-26 (Everywhere, Playgrounds). ↩

- Huizinga 1949, 173. ↩

- Huizinga, 1949 (originally published in 1938 as Homo Ludens: Proeve eener bepaling van het spel-element der cultuur). ↩

- The work of Jean Piaget, Roger Caillois and Lev Vytgovsky, to mention just a few of the most relevant early authors pioneering play studies, has argued the importance of play in the development of culture and learning, and posited game as a tool of civilisation. See, respectively, Piaget, 1962; Caillois, 2001 and Vytgovsky, 2016. ↩

- "(games) cannot found or produce anything for it is in their nature to cancel their results, as opposed to work and science that capitalise their results and, to a greater or lesser extent, transform the world.” Caillois, 1962, 22. Translated by the author. ↩

- Where subjective agency is the awareness of initiating and managing one’s own volitional actions in the world, asubjective agency refers to the agency of forces not controlled by the subject, such as weather, serendipity or chance, etc. ↩

- “If a designer (…) can make safe spaces that allow the negotiation of real-world concepts, issues and ideas, then a game can be successful in facilitating the exploration of innovative solutions for apparently intractable problems.” Flanagan 2009, 261. ↩

- The term “dialogic” is adopted in its basic sense of using an inter-personal, shared dialogue to explore the meaning of something. The term keeps most of its original meaning as used by Bakhtin, to refer to the necessary multiplicity of perspectives and voices in discourse and all signifying practices (Bakhtin 1981). That said, it is also hued by Sennett’s more recent use of “dialogic” as opposed to dialectic, in the sense of an empathic, curious attention to the implicit intentions behind a speaker’s actual words, which results in a mutual exchange for its own sake “where strangers can dwell in one another and where discussion can take an unforeseen direction.” Sennett 2013, 23. ↩

- See Christopher’s Dell take on improvisation as a city-making endeavour, the relevance of chance, and, specifically, “the foundational role contingency plays” in perceiving and making the city. Dell 2019, 8. ↩

- Flanagan 2009, 261. ↩

- Archispiel is an urban design game created for Magaluf Reset: Proyecto, Juego y Acción Estratégica [Magaluf Reset: Design, Play and Strategic Action ↩

- Barcelona Radical Landscapes, 4th-5th year design studio in ETSALS School of Architecture of La Salle (URL), faculty Roger Paez and Pedro Garcia. For more information, see Paez 2022. ↩

- MIAD: Master’s in Integrated Architectural Design; ETSALS School of Architecture of La Salle; La Salle Barcelona Tech Campus; Universitat Ramon Llull ↩

- Alejandro Arangú, Xènia Armengol, Uthman Bamalli, Dorian Bella, Agustina Cainzo, Albert Chavarría, Victòria Comamala, Edy Espinal, Sandra Fischer, Alex Font, Ronald Grebe, Kateryna Grechko, Marco Mosca, Alaa Osman, Charisa Paredes, Berta Prats, Laura Prudence, Carlota Puigrefagut, Samantha Redfern, Susana Romeo, Aurora Santallusia, Joana Solà, Surita du Toit. ↩

- ‘Movement’ maps means of transportation; ‘Roofs’ maps roofs and light-shafts; ‘Corners’ maps spatial configuration of street intersections; ‘Levels’ maps built structures heights; ‘Streets’ maps street hierarchy based on activity; ‘Structures’ maps load-bearing support elements; ‘Hidden geometry’ maps temporary structures such as parked vehicles and shipping containers; ‘Hard surfaces’ maps non-porous ground areas; and ‘Time’ maps temporal distances from each square to the three existing entrances to the site. ↩

- Such as Zona Franca Consortium, Port Authority, Municipality, Public Development Agency, Regional Government, Private Real-estate Investors, Neighbourhood Associations and Activist Groups. ↩

- Such as Millenials, Art, Knowledge, Well-Being and Talent. ↩

- El Núvol, like any game, is subject only to its own rules; they determine what is permissible within its limited range of play. Thus, its scope is free of any shared moral structures. ↩

- Cities as Playgrounds: New models for urban play, civic engagement and sociality. Directed by Larissa Hjorth and Clancy Wilmott, organized by RMIT Europe (https://www.rmit.eu/), with Urban Futures Enabling Capability Platform (https://www.rmit.edu.au/research/research-expertise/our-focus/enabling-capability-platforms/urban-futures) and Elisava (https://www.elisava.net/en). ↩

- See https://www.barcelonadesignweek.com/ ↩

- Ellis Bartholomeus, Jill Didur, Emma Fraser, Seth Giddings, Larissa Hjorth, Troy Innocent, Sybille Lammes, Colleen Macklin, Andrea Rosales, Miguel Sicart, Bart Simon and Clancy Wilmott. ↩

- This section is partially extracted from Speculative Urban Futures COST Action Proposal (https://www.cost.eu/cost-actions/), presented to the European Cooperation in Science and Technology and currently under review. ↩

- By 2080, 80% of the Earth’s 11 billion human inhabitants are expected to live in urban areas—that amounts to 8.8 billion people, 114% of the current world population. See United Nations 2017. ↩

- These “facts” were organised in the five thematic fields described above (demography, society, mobility, environment and post-humanism), and took the form of “what if” questions. ↩

- Such as “in 2080... ‘…much of civilization has been relocated to the polar regions’ (demography), ‘…the average employee works less than 20 hours per week’ (society), ‘…50.000 people live in the first successful nomadic floating city roaming the oceans’ (mobility), ‘…asteroid mining has evolved into a huge industry’ (environment) or ‘…voluntary amputations to graft prosthetic limbs boosting strength and endurance are available to the upper classes’ (post-humanism).” ↩

- A second deck of cards will allow teams 1 and 2 and teams 3 and 4 to have the same cards so they may use them in the next phases. ↩

- Barcelona Radical Landscapes, 4th-5th year design studio in ETSALS School of Architecture of La Salle (URL), faculty Roger Paez and Pedro Garcia. For more information, see Paez 2022. ↩

- Infrastructures for Public Space Interaction, MEATS Master’s degree in Ephemeral Architecture and Temporary Spaces, Elisava Barcelona School of Design and Engineering (UPF), faculty Roger Paez, Manuela Valtchanova, Curro Claret and Toni Montes. For more information see Paez and Valtchanova 2021. ↩

- MEATS: Master’s degree in Ephemeral Architecture and Temporary Spaces, http://meats.elisava.net/; Elisava Barcelona School of Design and Engineering, https://www.elisava.net/en; Universitat Pompeu Fabra, https://www.upf.edu/home ↩

- Balwant Sheth School of Architecture, https://architecture.nmims.edu/; Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies, http://www.nmims.edu/ ↩

- Dalia Al-Akki, Jana Antoun, Juan Arizti, Marta Borreguero, Elena Caubet, Nishil Desai, Ines Fernandez, Tanvi Gupta, Stephanie Ibrahim, Tracy Jabbour, Yunling Jin, Jad Karam, Sajol Kinariwala, Louis Kurian, Selen Kurt, Alexa Nader, Joelle Nader, Assil Naji, Mokshuda Narula, Tiago Rosado, Eirini Sampani, Dhruv Seth, Montserrat Sevilla, Rupal Shah, Brentsen Solomon, Sajitha Varghese, Kuan Yi Wu. ↩

- BCNEcologia 2019,115-127. ↩

- Dell 2019, 8. ↩

- See Elvira and Paez 2019, 387. For a further discussion on current shifting designer authorship, see Allen 2000: 41; Elvira 2005; Ortega 2017: 47; and Paez 2019: 312. ↩