1Introduction: How this world was made

The version of design that was shaped and perfected during the 20th Century played a huge role in the making of the modern (global northern) world. Whilst design’s potential as a contributor to the making of worlds is clear, its methods, metrics and purposes have led to a world that is increasingly being revealed as broken and unsustainable. Design today is complicit in the breaking of the world. This essay describes a practice-based design research approach to the making of other worlds. Borrowing from the literary devices of counterfactual or alternative histories and imaginative fiction, as well as an emphasis on extensive historical research, it aims to facilitate the development of new approaches to design that are informed by alternative ideologies, methods and motivations.

As Ursula K. Le Guin, one of the leading creators of alternative fictional worlds, once suggested:

“Imaginative fiction trains people to be aware that there are other ways to do things and other ways to be. That there is not just one civilisation and it is good and it is the way we have to be” (Curry 2018).

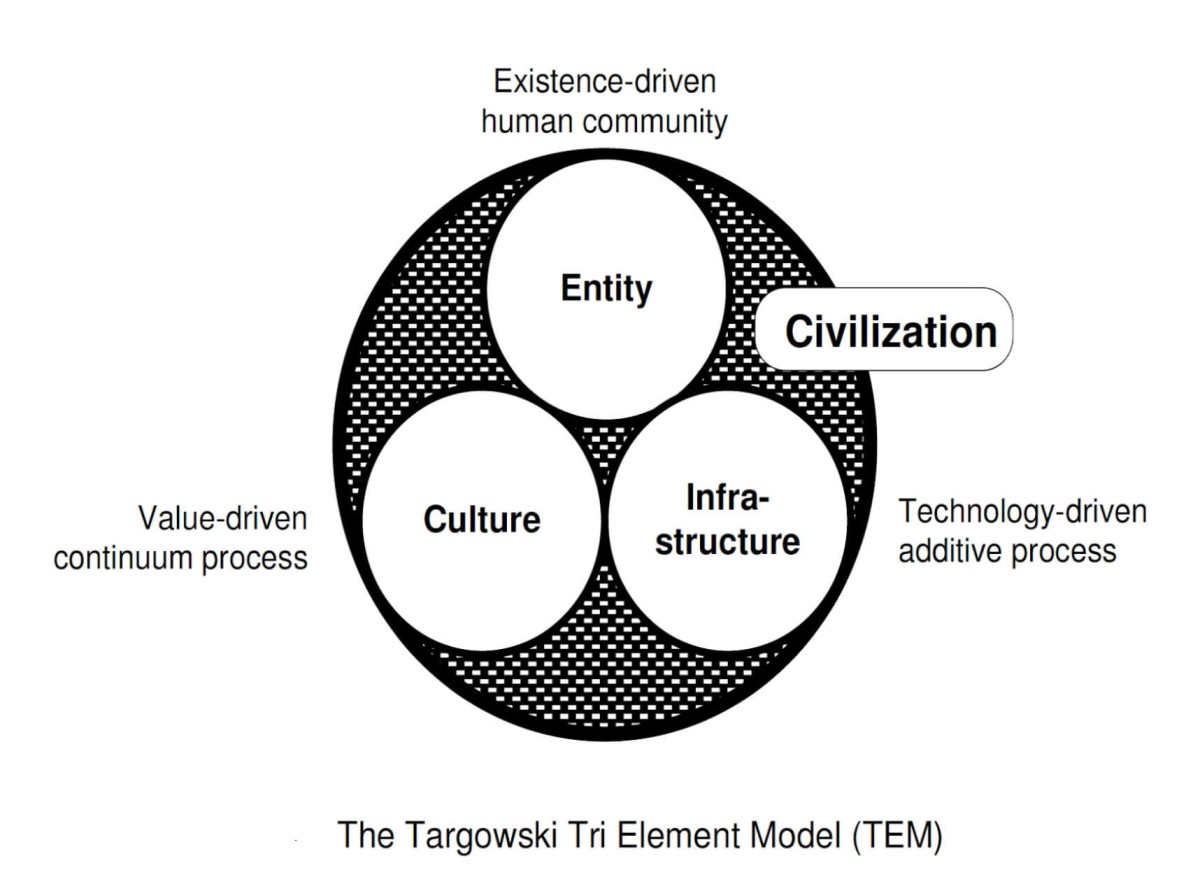

Le Guin explored social and political alternatives in her fiction as well as using her work to cast a critical eye on the status quo. In the context of this essay, Le Guin’s use of the word “civilisation” (as a more specific term than “world”) is particularly helpful when approached from the perspective of Andrew Targowski’s (2004) theory or “grand model” of modern civilisation, the Tri Element Model (Fig. 1).

Targowski makes a differentiation between culture and infrastructure, with culture being based on relatively stable values or belief systems whilst infrastructure changes incrementally through time via new developments in technology. This model defines the contemporary state of design: 20th-century value systems objectified through the latest technological advances. This facilitates the iterative development of products and provides a neat lineage both from the past and, more importantly, into the future (Auger, Hanna and Encinas 2017).

2Key problems with design today (and the history that got us here)

It is undeniable that design has contributed enormously to improvements in the quality of people’s lives through (amongst other things) the industrial production of domestic goods and the related enhancements of comfort, security and wellbeing. The dominant version of design practised today largely has its origins in the key reforms of the 19th Century which took place in the United Kingdom under the direction of the Government Schools of Design (founded in 1837). This movement laid the theoretical foundations for numerous designers and artistic enterprises at the end of the 19th Century and into the early decades of the 20th Century, including Peter Behrens, the Wiener Werkstätte, and the Bauhaus (Oshinsky 2006).

Design’s contribution to society during this period established its reputation as a force for cultural good and continues to influence how design is perceived and practised today. (One recent example of this continuing thread is the EU-sponsored New European Bauhaus initiative.) A fundamental shift took place in the 1920s, however, that complicated the purpose of designed artefacts. Here the economist and design enthusiast John Heskett (2017) describes some “basic facts about design as a form of practice”:

• The main area in which design is practised is business. There is a tendency for some designers to try to ignore this basic fact of their existence, which is yet another aspect of the problems in giving design credibility, but it will not conveniently disappear.

• As a business activity, design must be judged in terms of contributions to profitability. If it cannot contribute, then it cannot be regarded as of any use in business.

Design has been complicit in the development of business practices since Alfred P. Sloan, the boss of General Motors, came up with a plan to keep people buying new cars. Sloan introduced annual cosmetic design changes to convince car owners to buy replacements each year, essentially inventing the notion of planned obsolescence that is still prevalent today. In his biography he wrote: “The changes in the new model should be so novel and attractive as to create demand … and a certain amount of dissatisfaction with past models as compared with the new one” (Sloan 1990, 265). This historical moment could be viewed as instrumental in cementing design’s role in the development of capitalism and a gradual divergence away from the purer values that were embodied in the design artefacts of the 19th and early 20th Century and towards a more conspicuous form of consumption.

In the pursuit of profits, designers have adopted certain problematic modes of practice, approaches towards resources, and processes of evaluation. “Progress dogma” is the fundamental modernist value system: the belief that technological development will inevitably lead to a better future (Auger, Hanna and Encinas 2017). As political theorist Langdon Winner notes:

It is still a prerequisite that the person running for public office swear his or her unflinching confidence in a positive link between technical development and human well-being. (Winner 1986, 5).

This belief leads to a system of almost zero self-critique and little room for reflection on the more problematic implications of designed artefacts. In terms of resources, design’s dubious use of materials may be traced back to the colonial era, when raw materials were exchanged for the “precious commodity” of European civilisation (Chandler 2014). Still today, designers focus mainly on the object – its aesthetic qualities and performance – and use whatever materials are necessary to create the most desirable product, regardless of the ethical implications.

Branding, planned obsolescence, and non-repairability all contribute to the negative effects of consumer capitalism. “Future nudge”, or the persistent tendency towards iteration of the existing lineage, limits design to only what the product could conceivably evolve into (Auger, Hanna and Encinas 2017). But are the decisions made many product generations ago still the ideal ones? In fact there is much to suggest the opposite, that systems and products require radical rethinking for our rapidly changing times.

The reduction of possibility happens not only on the object-level but on the level of infrastructure and larger systems and networks as well. Meta-systems like energy infrastructure become invisible, with the designer simply acting within the system. We typically design – and teach students to design – for the system as it is now, without questioning or encouraging students to question how it could or should be. This clear shortcoming in design pedagogy may be remedied using the counterfactual methods outlined in the following sections. First, however, some background is needed to explain the history of counterfactual speculation.

3Background: Towards the building of other worlds

The BBC World Service recently asked listeners worldwide: “Which part of history would you change?” A wide range of crowdsourced counterfactuals (reversing legacies of colonial rule, erasing national borders, even altering influential literary texts) were gathered from respondents, with aims such as reducing inequality, preventing conflict and avoidable tragedies, and so on (BBC 2022). The exercise illustrates both the growing popularity of counterfactual histories and the way in which they represent a safe space for exploring hypothetical alternatives – not to undo the past, but to help us think beyond the narrow pathways we have inherited in order to create better futures.

Counterfactuals have a long and diverse history across many cultures. They often turn on political or military events, such as a different election outcome (Franklin Roosevelt being defeated in 1940 in Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America) or the outcome of a war (the victory of the Axis Powers in Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle). Sometimes history is “flipped” in a prolonged “what if” thought experiment, as in Malorie Blackman’s novel series Noughts and Crosses (2001- ), in which Europe has been colonised by Africa. They may also serve a pedagogical purpose by revealing the path of a life unloved or unlived, as in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1853) and Frank Capra’s film It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). In many fiction plots the device is played for dramatic effect, with ambiguous or negative consequences: Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Years of Rice and Salt (2002), for example, in which the Black Death kills 99% of Europeans, or Stephen Fry’s Making History (1996), where going back in time to kill Hitler only results in a more competent despot taking his place. H. G. Wells’s A Modern Utopia (1905), as the title suggests, is a positive example: Wells uses the device to sketch a kinder, gentler, thriving world that exists on a parallel timeline in which, among other changes, Jesus Christ was not persecuted and ancient Rome never fell. In an academic design context, counterfactuals in a broader sense have been used as “speculation pumps” to generate constructive thought experiments leading to new outcomes (Oulasvirta and Hornbaek 2022).

Historians especially tend to focus on military "decision points" – a battle lost instead of won, a war avoided instead of launched – at which events could have taken another path (Bernstein 2000). Alternatively, counterfactuals imagine the absence of powerful individuals from specific events to speculate on how things might have played out differently. (In the context of design, for example, this might be something like: what if Steve Jobs never visited Xerox Parc in 1979?¹) From a historian’s perspective, this approach offers rich potential for re-imagining how the world might have evolved under alternative circumstances. Imaginaries based on a poignant counterfactual history can offer thought-provoking insights and perspectives on contemporary life as well as an examination of the past. Since history is “often written by the victors, it tends to ‘crush the unfulfilled potential of the past’, as Walter Benjamin so aptly put it. By giving a voice to the ‘losers’ of history, the counterfactual approach allows for a reversal of perspectives” (Deluermoz and Singaravélou 2021, 49).

Fredric Jameson, also invoking Benjamin, provides a useful summary of the broader “social function” of mainstream speculative fiction, whether in literature, film, or television:

in a moment in which technological change has reached a dizzying tempo, in which so-called "future shock" is a daily experience, [sci-fi] narratives have the social function of accustoming their readers to rapid innovation, of preparing our consciousness and our habits for the otherwise demoralising impact of change itself. They train our organisms to expect the unexpected and thereby insulate us, in much the same way that, for Walter Benjamin, the big city modernism of Baudelaire provided an elaborate shock-absorbing mechanism for the otherwise bewildered visitor to the new world of the great 19th-century industrial city. (Jameson 1982, 151)

This has, in effect, also been the function of commercially driven narratives and imaginaries around mainstream design, from world fairs to promotional advertisements, which declare in effect: Get ready for the future! In E. L. Doctorow’s novel World’s Fair (1985), for example, the father describes the way corporate visions are realised as the family leaves the 1939 New York World’s Fair:

It is a wonderful vision, all those highways and all those radio-driven cars. Of course, highways are built with public money,” he said after a moment. “When the time comes General Motors isn’t going to build the highways, the federal government is. With money from us taxpayers.” He smiled. “So General Motors is telling us what they expect from us: we must build them the highways so they can sell us the cars. (285)

As the above passage shows, speculative fiction can also serve a critical or self-reflexive function. Rather than simply selling or packaging or preparing people for “the future” (always singular), speculation can also open up new possibilities and envision alternative futures (always plural) beyond the narrow path of iterative design and the blinkered view of “capitalist realism” (Fisher 2009). It is not limited to the future, either: a rich parallel history of what-if counterfactuals exists in tandem with future-oriented speculations. The anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1989) famously defined the term “faction” as “imaginative writing about real people in real places at real times” – here instead we are engaging in unreal or parallel or alternative times.

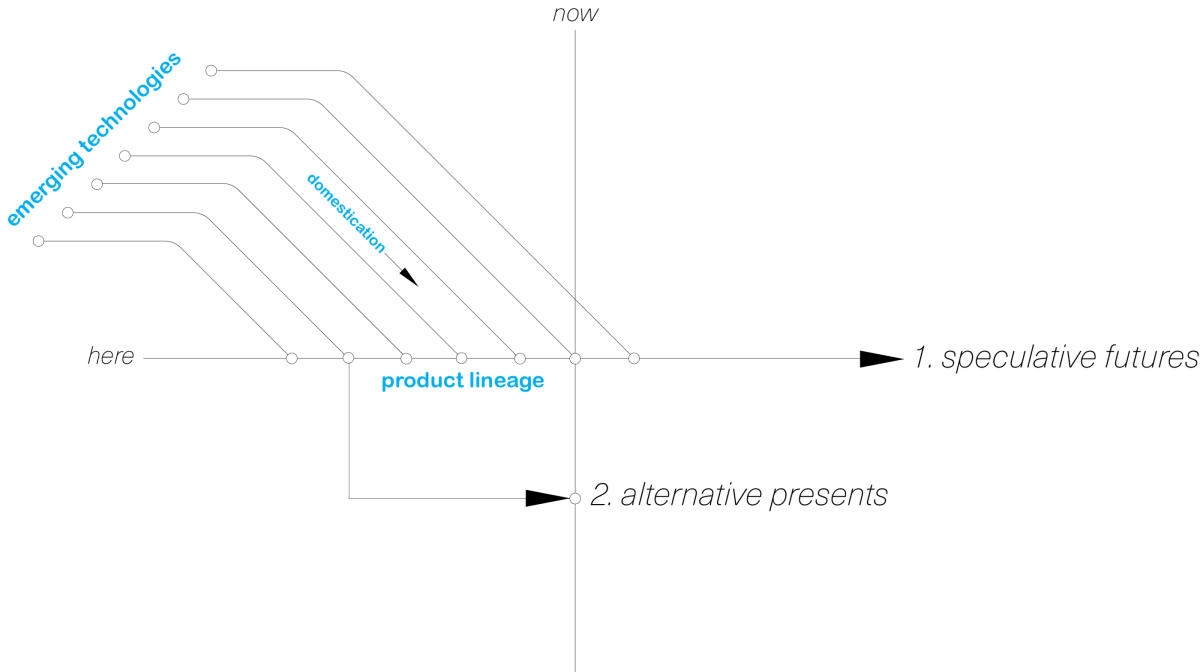

This then is the basic premise, and promise, of counterfactual histories especially as applied to design pedagogy: to break out of constraining lineages and narrow pathways through the imagining of alternative narratives and the application of alternative values. Such speculative proposals “question existing paradigms through the use of different ideologies to those currently directing product development. These are speculations on how things could be, had different choices been made in previous times” (Auger, 2012) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Alternative presents and speculative futures. The technology on the left side represents laboratory research – the higher the line the more emergent the technology. As we move into the future on the right side, speculative designs exist as projections of the lineage. Counterfactuals or alternative presents, on the other hand, step outside the lineage at some relevant point in the past to reimagine our present.

4Method: Counterfactuals in design

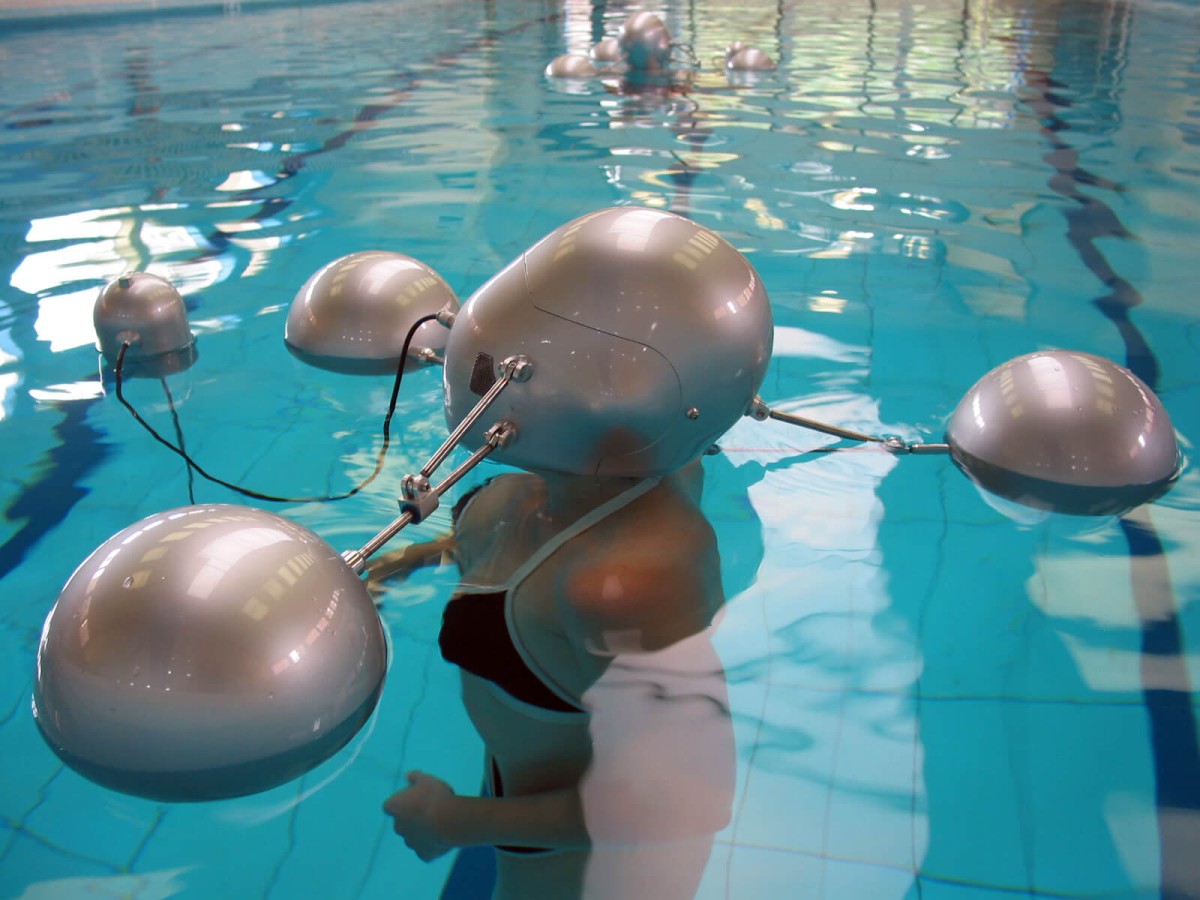

Counterfactuals have previously been used under the guise of speculative design. One very early example is Auger-Loizeau’s Iso-phone (2003) (Fig. 3). Developed during the fast-growth period of the mobile telephone, the project imagined an alternative lineage for telecommunication that evolved from Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s famous red British telephone box. Its thick walls and glass acted to dislocate the caller from the noise of the outside world, in turn creating a neutral space that facilitated a focus on the phone conversation. The Iso-phone took this notion several stages further through the use of sensory deprivation theory. The resulting telephone prioritised the quality and immersive nature of the experience and acted to question the increasingly dominant lineage of the always on, always available, always distracted mobile phone experience.

Fig. 3. The Iso-phone is a telecommunications concept providing a service that can be described simply as a meeting of the telephone and the isolation tank. By blocking out peripheral sensory stimulation and distraction, the Iso-phone creates a telephonic space of heightened purity and focus.

In a more recent example, A New Scottish Enlightenment, Mohammed J. Ali proposed a different outcome to the 1979 Scottish independence referendum (Debatty 2014) (Fig. 4). In Ali’s counterfactual a “yes” vote led to the creation of a new Scottish government whose ultimate goal was the delivery of energy independence for its citizens, paving the way for a future free from fossil fuels. The project was first exhibited three months before the second Scottish independence referendum in September 2014. This starting point (a simple yes or no vote) resonates because it vividly presents to the audience a life that clearly and concretely could have been. The second aspect that gives the project wider relevance is the agenda used to drive extrapolation from its fictional starting point – a simple value shift on energy generation and distribution. By defining citizen energy independence as a national goal, it becomes possible to begin outlining the ways through which this might happen. Other important early examples of a counterfactual approach to design include Sascha Pohflepp’s The Golden Institute and James Chambers’ Attenborough Design Group (see Auger 2012; Dunne and Raby 2013).

Fig. 4. A New Scottish Enlightenment - the home workshop inventor working on the Salter Duck (developed in the 70s and early 80s by the scientist, Stephen Salter, at Edinburgh University). It takes the form of an energy harvesting wave machine.

5Counterfactuals applied to design education

Counterfactuals provide an almost surreptitious method of combining design theory with practice. Through a rigorous analysis of history as it relates to a specific subject, the designer can identify the key elements that are problematic when viewed through a contemporary lens of practice. The approach can expose dominant structures of power and the influence these have on design culture and metrics: for example, the pervasive influence of legacy systems and the attention economy, and how they limit the imagination and constrain possibility.

So, how to teach a different version of design? Here are a few key steps that describe a new methodology based on the counterfactual approach. The design brief is structured in the following manner:

• Definition of the theme or subject followed by a broad mapping of its related systems. These can then be examined historically to create a detailed and diverse timeline of the subject – the key moments that led to the current world (for example, a political decision, an invention, a celebrity endorsement, a natural disaster). These can then be critically analysed to identify the event(s) that contributed to the problematic contemporary situation.

• The creation of a counterfactual timeline based on a different outcome of an event identified on the real timeline. One of the key benefits of this approach is the necessity to understand complex histories and how they inform or influence design practice. Experiment with different themes and examine the potential consequences. Remember that the further back in time the more divergent the alternative present will be, and therefore more fictional and complicated to manage – as Ray Bradbury’s classic tale “A Sound of Thunder” illustrates (Bradbury 2005).

• The design of things along the new timeline: hypothetical products, advertising campaigns, images, texts – evidence of the new value system in action. In a longer project this can culminate in well-rendered imaginaries of an alternative present.

6Approach in pedagogical practice

We formalised the counterfactuals method further for a workshop at the École normale supérieure Paris-Saclay. The students comprised a mix of master and PhD candidates in the design research department. This course started with a series of theoretical classes on a critical history of design before moving onto the creation of factual timelines - each chosen by the student to align with their particular interest or focus. Numerous themes emerged including a rethinking of approaches to ageing, based on the elimination of the royalist doctrines of 18th century France; an alternative history of agriculture, with the tool acting as an intermediary between the person working the soil and their working environment; and an examination of the modalities for a deployment of queer, feminist and trans-feminist archive design forms in everyday life. To conclude this essay, we will describe in more detail, two projects that emerged from the workshop to illustrate the counterfactuals method in action.

Design vs engineering: an automobile counterfactual

Louison Filippi, a 1st year master student with a background in engineering, decided to approach the counterfactual project through the subject of the automobile. According to J.G. Ballard, the man in the motorcar is the key image of the 20th Century:

It sums up everything

The elements of speed, drama, aggression.

The junction of advertising and consumer goods.

The technological landscape.

The sense of violence and desire.

Power and energy…The styling of motorcars, and the American motorcar in particular, has always struck me as tremendously important, bringing together all sorts of visual and psychological factors. As an engineering structure the car is totally uninteresting to me. I’m interested in the exact way in which it brings together the visual codes for expressing our ordinary perceptions about reality. For example, that the future is something with a fin on it.

And the whole system of expectations contained in the design of the car.

These highly potent visual codes can be seen repeated in every aspect of the 20th century landscape. What do they mean? Have we reached the point now in the 70s where we only make sense in terms of these huge technological systems. I think so myself, and that it is the vital job of the writer to try to analyse and understand the real significance of this huge metalised dream.(Cokeliss 1971)

Ballard’s words from the 1971 short film Crash! (based on his novel) eloquently describe the place of the automobile in 20th-century culture, making it the perfect subject for a counterfactual project. What if a different set of values had informed the development and evolution of the motorcar over the past 100 years? If it is the vital job of the writer to analyse the significance of these technological dreams, then surely it should be the job of the designer to understand our complicity in their creation and realisation.

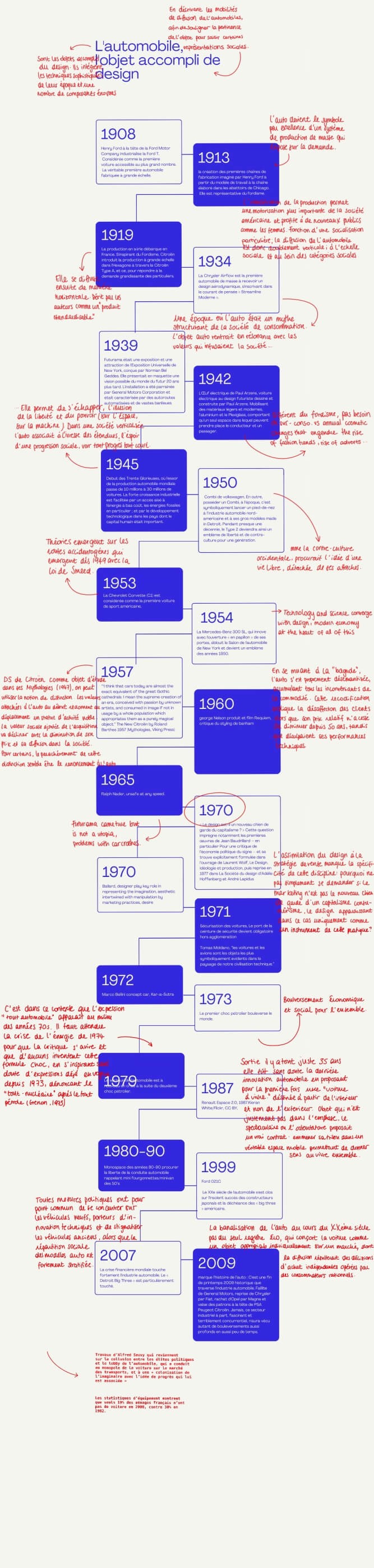

The critical point of focus chosen for Filippi’s counterfactual was General Motors’ Alfred P. Sloane’s introduction of annual cosmetic design changes (as discussed in the Introduction). Sloane’s consumerist vision for the future of the car industry became, by extension, a blueprint for the consumer capitalist system we live in today. What if the “shift from a needs to a desires culture”, famously articulated by Paul Mazur of Lehman Brothers in the 1920s, never happened? What would the present day automobile look like had it followed instead the value system of General Motors’ competitor Henry Ford, and the purist engineering logic of the Model T?

For the first-year master’s students we use the counterfactual brief to build a foundation for the major second-year project. Filippi is currently in the process of developing the alternative timeline that will ultimately provide opportunities for designing artefacts informed by the alternative value system exemplified by Ford’s approach. Features of the new timeline included a culture of repair and design for optimal repairability, a valuing of durable, handmade objects, (re-)use of existing materials, knock-on effects in adjacent industries such as fashion, and so on.

Fig. 5. Louison Filippi’s timeline relates to the evolution of the motorcar during the 20th century. She has a particular interest in the relationship between the fields of engineering and design, recognising the more technical approach of Fordism as compared to the intervention of Alfred P. Sloan who, as boss of General Motors Corporation, introduced annual cosmetic updates. This could be viewed as the moment that launched the consumer society.

Automated vs symbiotic: a smart home counterfactual

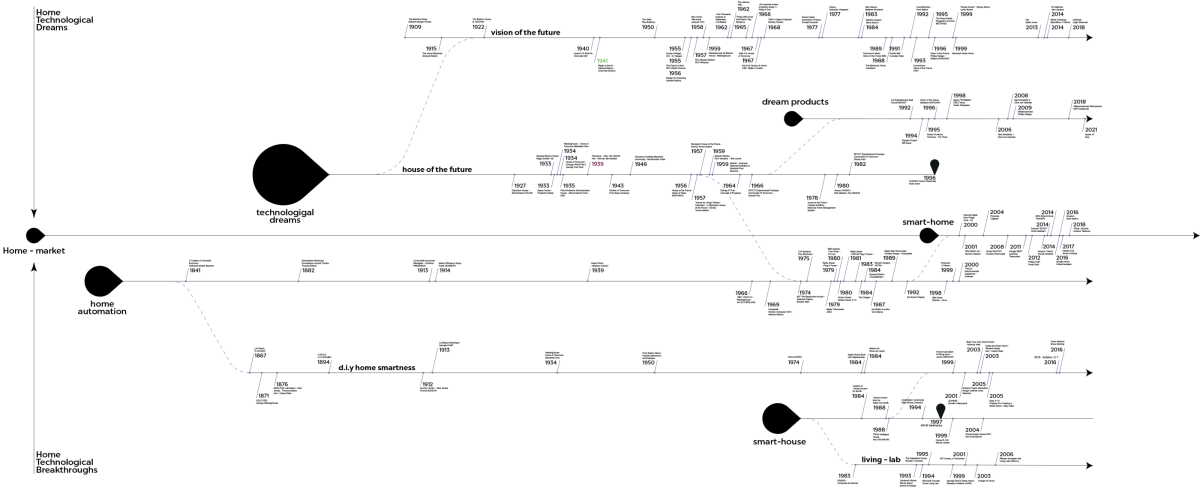

PhD candidate Valentin Graillat used the counterfactual approach to structure his research into an alternative version of the “smart home”. At the core of his research project is a questioning and re-framing of the word smart and its enduring role in representing imaginaries of (utopian) technological futures.

Fig. 6. Valentin Graillat’s smart-home timeline selectively traces the history of the smart-home concept, from the mid-19th century to the present day. The part on the right covers developments in the cultural field: films, installations, exhibitions and forward-looking projects that have shaped our Technological Dreams of the automated-home. The part on the left relates to technological developments in the field - from the first prototypes of domestic automation to recent advances in technology. The two parts converge in the 2000s with the concept of the smart-home and the first examples of automated technologies shifting from the context of research and future dreams towards everyday life in the context of the home.

The genesis of the notion of smart homes can be found in the "Houses of Tomorrow", conceived in the United States during the Cold War by the hegemonic corporations of the time (Disney, Monsanto, General Electric). These glamorous visions of the future, full of jetpacks and robot servants, had the primary role of stimulating the consumption of new domestic appliances (refrigerators, televisions, vacuum cleaners) through the crafting of an alluring spectacle. In the long term, these imaginaries had a secondary performative effect: they conditioned our expectations for the future by positioning as desirable a technologically-driven lifestyle focused on consumption, disengagement, and entertainment. Yesterday's houses of tomorrow crystallised a value system (comfort, efficiency, convenience, distraction) that continues to inform technological research and development today, in spite of deteriorating social conditions and urgent environmental considerations.

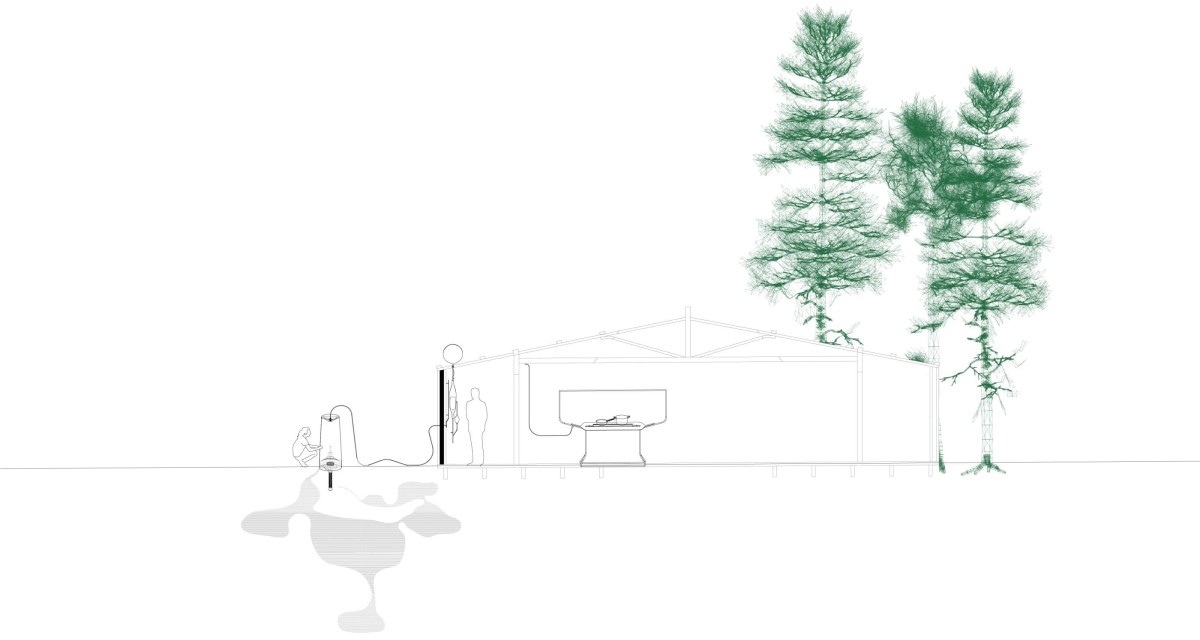

In developing the “true” historical timeline, Graillat identified a few key moments that would have provided an opportunity for an alternative present. In 1971 the US reached peak oil production, but in 1973 it was violently shaken by the World Oil Crisis. President Nixon signed the “Independence Project” and intended to initiate a strategic policy to develop domestic energy production. Apart from a few alternative projects that were situated in a rural counterculture, the policy ran out of steam during the decade and was replaced by a re-investment in import policies at the end of the 1970s. Graillat asks: what if the American government had reinforced investment on domestic energy production, requisitioning large companies such as Honeywell to develop domestic technologies, and allowing citizens to produce bio-energy in an urbanised context?

The technological realisation of the smart home, which began in the mid-1980s, would then have radically integrated alternative research such as that of the Farallones Institute in Berkeley, whose objective was to develop appropriate technologies (e.g. using biogas) in the domestic field. With support from the large companies that dominated the technological sector at the time, a different version of smart would have emerged - less sensor/computation and more aligned with natural systems and habitats. Graillat’s project speculates that the domestic technologies developed in this context would have allowed the inhabitants of residential and urban areas to produce energy on a domestic scale through co-existing with living organisms present in their environment.

Fig. 7: Since the 1980s, the biologist community has been interested in the significant methane emissions of termites - subterranean insects that feed on the frameworks of houses that are prevalent on American south eastern coasts and northern Australia. The project speculates that through technological developments, a habitat-scale domestication of these insects would have facilitated the valorisation of the gas emitted by their nests through a micro-methanation system. Maintained by the inhabitants from cellulose-rich materials on a suburban scale, the process would produce small quantities of biogas for food and lighting.

7Conclusion: Theory into action

One unexpected result of the workshop was the counterfactual timeline as an approach to the archive. The writer of historical fiction, Hilary Mantel, made some poetic observations on the paucity of our recorded history during her Reith series of lectures (2017):

Evidence is always partial. Facts are not truth, though they are part of it – information is not knowledge. And history is not the past – it is the method we have evolved of organising our ignorance of the past. It’s the record of what’s left on the record. It’s the plan of the positions taken, when we stop the dance to note them down. It’s what’s left in the sieve when the centuries have run through it – a few stones, scraps of writing, scraps of cloth. It is no more “the past” than a birth certificate is a birth, or a script is a performance, or a map is a journey. It is the multiplication of the evidence of fallible and biassed witnesses, combined with incomplete accounts of actions not fully understood by the people who performed them. It’s no more than the best we can do, and often it falls short of that.

With its focus on underrepresented groups, unrealised possibilities, and knock-on effects for the present and future, a theme that deserves further exploration is Dylan Fluzin’s (Master 1) queer archive or “un-archive”; this adds another factor that separates history from the past. As Karen Barad has argued, “the past is never closed, never finished once and for all” (Barad 2010, 264). Therefore it is fruitful to challenge “rhetorical forms that presume actors move along trajectories across a stage of spacetime (often called history)” (240). “Queering time” – bending the straight line of technological progress, questioning causality and linearity, and countering hegemonic conceptions of time (such as traditional archival practices) in order to open up new possibilities and discover alternative realities – is one way to constructively deploy counterfactual histories in design education.

We began this essay with a discussion of design’s last key reformation. That reformation was necessary due to the dramatic cultural upheaval taking place during the Industrial Revolution, and it secured design’s role as a mediator between technological progress and its manifestation in the contexts of everyday life. Design is now in dire need of a new reformation – its methods, and more importantly its values, are badly out of date. The additive approach to technological change, championed by governments and corporations alike, will not provide the dramatic shifts that are necessary. Design’s history – predominantly white, male, Western, and so on – enforces a very narrow scope of possibility of what and who is celebrated, and by extension what and who has the power to determine “future histories” (to borrow another term from speculative fiction).

This history also dictates a narrowed scope in terms of how designed artefacts are evaluated. To take an obvious example, Dieter Rams’ (1976) spare, functional ten principles of “good design” occupy an outsized influence as a metric for the evaluation of all contemporary designed artefacts. Here perhaps is the most vital use of counterfactuals in design, and their most valuable contribution to design education: to allow different paths to emerge that were drowned out by the dominant or “standard” narrative(s). Conjuring into being or simply recognising alternative histories can open up valuable future paths, and create space for rich new possibilities and new imaginaries to flourish.

• Auger, James. 2012. Why Robot? Speculative design, the domestication of technology and the considered future. PhD thesis, Royal College of Art.

• Auger, James. 2013. “Speculative Design: Crafting the Speculation.” Digital Creativity, 24(1): 11-35.

• Auger, James, Julian Hanna, and Enrique Encinas. 2017. “Reconstrained Design: Confronting Oblique Design Constraints.” NORDES (Nordic Design Research) 2017: Design and Power. Vol. 7.

• Auger-Loizeau. 2003. Iso-phone. https://auger-loizeau.com/isophone.html

• Barad, Karen. 2010. “Quantum Entanglements and Hauntological Relations of Inheritance: Dis/continuities, SpaceTime Enfoldings, and Justice-to-Come.” Derrida Today, 3(2): 240-268.

• BBC World Service. 2022. “Pick of the World: Which Part of History Would You Change?” (3 December) https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/w3ct41xr

• Bernstein, Richard B. 2000. “Review of Ferguson, Niall, ed., Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals.” H-Law, H-Net Reviews. http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=3721

• Borgmann, Albert. 1987. Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life: A Philosophical Inquiry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

• Bradbury, Ray. 2005. A Sound of Thunder and Other Stories. New York: William Morrow.

• Chandler, Arthur. 2014. “Fanfare for the New Empire: The French Universal Exposition of 1855.” http://www.arthurchandler.com/paris-1855-exposition

• Cokeliss, Harley, director. 1971. Crash! BBC.

• Curry, Arwen, director. 2018. Worlds of Ursula K. Le Guin. https://worldsofukl.com

• Debatty, Régine. 2014. “A New Scottish Enlightenment.” We Make Money Not Art (7 July). https://we-make-money-not-art.com/a_new_scottish_enlightenment/

• Debord, Guy. 1994. The Society of the Spectacle. London: Rebel Press.

• Deluermoz, Quentin and Pierre Singaravélou. 2021. A Past of Possibilities: A History of What Could Have Been. New Haven: Yale University Press.

• Dunne, Anthony and Fiona Raby. 2013. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

• Fisher, Mark. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Winchester: Zero Books.

• Friedman, Milton. 1970. “A Friedman Doctrine: The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits.” New York Times (13 September). https://graphics8.nytimes.com/packages/pdf/business/miltonfriedman1970.pdf

• Geertz, Clifford. 1989. Works and Lives: The Anthropologist as Author. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

• Heilbroner, Robert. 1967. “Do Machines Make History?” Technology and Culture 8(3) (July): 335-345. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3101719

• Heskett, John. 2017. A John Heskett Reader: Design, History, Economics. London: Bloomsbury.

• Jameson, Fredric. 1982. “Progress versus Utopia; Or, Can We Imagine the Future?” Science Fiction Studies, Utopia and Anti-Utopia, 9(2): 147-158.

• Mantel, Hilary. 2017. “The Reith Lectures: Part One: The Day is for the Living.” (June 13). https://medium.com/@bbcradiofour/hilary-mantel-bbc-reith-lectures-2017-aeff8935ab33

• Mazur, Paul. 1928. American Prosperity: Its Causes and Consequences. New York: Viking.

• New European Bauhaus. “About initiative.” https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/about/about-initiative_en

• OECD. 2022. “Plastic pollution is growing relentlessly as waste management and recycling fall short.” (22 February). https://www.oecd.org/environment/plastic-pollution-is-growing-relentlessly-as-waste-management-and-recycling-fall-short.htm

• Oshinsky, Sara J. 2006. “Design Reform.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dsrf/hd_dsrf.htm

• Oulasvirta, Antti, and Kasper Hornbaek. 2022. “Counterfactual Thinking: What Theories Do In Design.” International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 38(1): 78-92.

• Rams, Dieter. 1976. “Ten Principles for Good Design.” Vitsoe. https://www.vitsoe.com/eu/about/good-design/

• Sparkes, Matthew. 2021. “2021 in review: 'Right to Repair' campaigners claim iPhone victory”, New Scientist (31 December). https://www.newscientist.com/article/2021-2021-in-review-right-to-repair-campaigners-claim-iphone-victory/

• Sloan, Alfred P. 1990. My Years with General Motors. New York: Currency Doubleday.

• Targowski, Andrew. 2004. “A Grand Model of Civilization.” Comparative Civilizations Review, 51(51), Article 7. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol51/iss51/7

• Triumph of the Nerds. 1996. “Great Artists Steal.” PBS. April 28. https://www.pbs.org/nerds/part3.html

• United States Senate. 1958. “Hearings: Volume 7.” Washington: US Government Printing Office.

• Winner, Langdon. 1986. The Whale and the Reactor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.