This conversation took place on July 10, 2024, during the Deleuze and Guattari Studies Conference & Camp at the Faculty of Architecture at TU Delft. It comments on the irony of purity, uncovering the hidden intensities embedded in everyday rituals and routines, to emphasize the latent, generative potential of constraint. Regimented habits, affective memories, and micro-regulations are reimagined not as limiting, but as formative of fields of tensions, whose very dissonance becomes the condition for inventive practices within daily life and spatial practice. From bedrooms to Gothic cathedrals, from design pedagogy to lived intensity, architecture emerges as a site of negotiation between form and sense, control and transgression, structure and desire.

Chris L. Smith was interviewed by Lena Galanopoulou

So, now we’re recording. Firstly, to give you a bit of a context; this conversation is part of a European program I’m involved in called Speculative Urban Futures, or SUrF. It’s an Erasmus+ funded initiative that looks at how speculative design pushes us to rethink and reshape contemporary urban realities. These conversations are one way we’re opening up different perspectives on the topic.

I’d like to begin with an irony, or maybe a productive contradiction, that I think can playfully frame the flow of our talk. So, when one hears the word oatmeal, I believe the first thought is ‘that clean food’ is usually associated with regulation in nutrition and dietary habits. I was surprised to learn that oatmeal is also the key word, or safe word one uses in sexual contexts, like in BDSM, to signal a limit or discomfort when normal linguistic signification isn’t operable. That duality made me think about how the structures we impose towards our living, what we eat, when we sleep, where we live, even our design practices, fuel at the same time a quiet rebellion against those same structures. So, I thought oatmeal would be a fitting entry point, as I would like us to discuss micro-regulations and speculate on how systems of control maybe promote alternative ways of designing, thinking, and dreaming. How might architectural thinking mirror or resist internalised systems of control.

Yes, that’s interesting. I'm a fascist eater, and I'm a fascist lifestyle person. I'm highly regulated. I am completely regulated in everything. So yes, I can tell you what I eat every day, because it repeats itself endlessly day-by-day. And yes, not oatmeal as such, but muesli, the same thing… oats, every morning. Not just because of how good it is for you, but also because it’s structured. I restrict what I eat as much as I restrict what I wear. I only have two colors, black and grey, because I can’t cope with more. If I have a choice of two things at a restaurant or two things at a clothing shop, that’s all I want. I don’t want to deal with menus or colour palettes. I don’t want to deal with a wardrobe, or a range of breakfasts, or a range of anything. So, I wake at the same time every morning. I eat the same things every day. I start writing at the same time every day. I have the same coffee breaks. And those blocks, blocks or little fascisms, are something I’ve stuck to.

… But I’m heavily regulated in such things in order that when I sit, when I sit to write, to think, to read, and to write again, I can be quite liberated. I think about it in design terms too. It's that classic story of architecture being about control and containment, regulation and rhythm. And that rhythm is probably more like a march than a contemporary dance rhythm. That is: columns, stairs, treads, there’s that high, high repetitious sort of march to it all. And architecture is always about that: containment and control. But the reason we do it, the reason we have it, is because of what it liberates. So, I live a lifestyle that is highly controlled and regimented in order to liberate other things.

So perhaps what you’re describing is how constraints can become enabling; regulatory systems that paradoxically establish the conditions for something new to emerge. It’s like going to the gym, you count reps, sets, timing. And that repetitive structure, even though it’s rigid, sets the frame for transformation. Do you see this kind of repetitive, almost ritualized structure as a generative condition?

It's an incredibly meditative sort of thing, but there's definitely nothing unusual about it, and it all connects to architecture as well. The Greeks were always about a type of stepping oneself through an argument. It’s the repetition of steps, like the mnemonics of a walking lecture. So, you could mount a large, long lecture and run a long and often complex sort of argument, because you're mentally stepping with it. And it's the rhythm of the walking, that rhythm that generates the space and liberates the thoughts.

Yes, I completely agree. What I’m thinking is that we often introduce a certain structure or organisation not simply to control, but to sort through experience, to classify, through iteration, what is meaningful enough to preserve. In a way, these systems allow us to determine what is worth continuing, or perhaps more accurately, what can be liberated through structure.

I think of when I was writing Bare Architecture, some time ago, I used the provocative example of the bedroom. You secure yourself from the chaos of the street, and the rain, and the clouds, and the hubbub of other people, and all this sort of thing, in a space. And that’s architecture. The architecture of the bedroom does this—it contains and controls. But we do it to release the germinal, what Deleuze and Guattari might call germinal forces. We design a bedroom to contain and control but we contain and control in order to dream and to fuck. (And you can’t dream well on the street.) So, that’s how tight, heavy structuring can sometimes be about what it liberates. And that architecture might even transform what we're doing in the bedroom.

Chris L. Smith, Bedroom legs, Sydney 2024.

And all these processes are now becoming part of a bedrooming and no longer just refer to sleeping (I refer here to Georges Perec, Species of Spaces and Other Pieces). These practices converge and evolve together into a new kind of composite act. Through this iterative layering, the bedroom takes on more functions, and in a way, it becomes difficult, even unimaginable, to separate those ritualistic activities from the space itself.

Yes, it's complex. I think it's a complex story that is told in two directions. Someone like Foucault, for instance, brings to light the idea that ‘public space’ is the least human of space. Oddly enough, what we call ‘public space’ is where you're highly regulated, and it probably always had this character. It would be odd to bleed on the street. And yet half the population bleeds regularly. Public space doesn’t accommodate the public, it regulates it. In public spaces, in those rare moments when we see someone bleed, or cry, or scream, it’s like you have to look twice. And yet, such things are entirely human expressions. These human expressions tend to be wedged into houses, or homes. And then, when we get to our homes, our homes have also become more and more regulated and about containment and control. On the one hand, modernists talked about liberation, the free plan, the open space, the dissolution of boundaries between interiors and exteriors. And yet, all of that is almost like the extension of a type of public realm into the interior… an extension of the regulation of what it is to be human. Now we can’t just retreat into our homes to bleed, cry or scream, we now have to retreat into bedrooms or bathrooms, to be a human animal. The latest iteration of this issue is the ‘mezzanine bedroom’. And so, what’s happened is that the kind of regulation we associate with public plazas, with civic space, that self-regulation, has made its way well inside architecture and now threatens to invade our very sleep. Where do people fuck now? Where do they scream?

Yes, this is particularly interesting; How public space renders such ordinary human expressions, bleeding, crying, screaming, as anomalies rather than norms. In the street, on the pavement, in the public eye in general, we’re subject to imposed regulatory regimes we don’t directly author. By contrast, in our home, in our bedroom, we become the designers of our own micro-regulations. There is something empowering in this self-determination, but at the same time, I wonder whether the most memorable or affectively charged moments are precisely those in which these structures destabilize; when the boundaries, the containers dissolve or mutate.

Perhaps this leads us to a next point: when and how do we intentionally contaminate our own regulatory systems? Could we think of those moments of interruption, breakdown, or excess as thresholds charged with intensity? For example, a bedroom crowded with people during a home party, or an empty, dark shopping mall at night are threshold moments when presence and absence collapse into one another. These, I think, are moments where structure fails or at least stretches, points in which architecture deals with liminality.

Yes, absolutely yes! And sometimes it's also about the contamination or collapse or the absence of the self too. We need to co-opt architecture and the fixed senses we have of the self. I play and keep playing—and will probably keep playing for my whole life—with an image, which is the image of what holds someone in place. That is, what holds someone (a self, a sense of self) in the geo-historic real. For example…. I know if I took this coffee cup and smashed it on the desk now, and I pushed it deep into your skull, you would die right here, right now, and forever and always this would be the case. There’s a geo—this place just here—and a historic—at just this time—character to the event. Like, it would always be here. Just here. And always. Just now. And architecture belongs to this spatio-temporal-real. But at the same time, there's this being constantly swept up, swept away, losing oneself—that's also going on.. And you know, if my thoughts roam a bit, I'm roaming. I'm becoming more liminal and not so tightly held to the geo-historic. I might be thinking of the dead, and of other places and of possible places, adrift. But it often takes both (presence and absence, the geohistorical and the liminal). There's this beautiful moment in the Mrs. Dalloway novel, where Clarissa Dalloway is on a bus going down Shaftesbury avenue and she feels all of London, the street, the swirling of everything—all the sounds, all the activity, all that which she loves… and it’s overwhelming, so she just reaches out and touches the seat in front of her. And this happens all the time. It's this beautiful, complex thing about having the geo-historic real, in a pinprick, versus a kind of liminality.

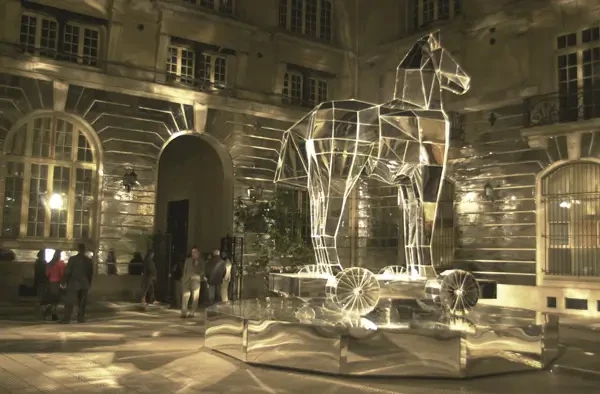

What you called a ‘threshold moment’ or the collapse that occurs between these two states is often intense and extensive. Years ago, maybe 2004 or 2005, I was in Paris for White Night—Nuit Blanche. All the galleries were open, all the museums open, everyone took to the streets at night and wandered. I was in this big courtyard, surrounded by a heavy Haussmann-style building. When I came into this space, this courtyard, there was someone with a little clicker counting how many people entered, so there wouldn’t be too many in any one space at once. Click, click click. In the big courtyard, in the middle, there was this massive glass and mirrored horse, about 12 metres high, a huge, fractal Trojan horse, with bouncing light everywhere. And I was standing there thinking: I'm so incredibly fucking lucky to be just here, just now, with this love, with this joy, with this horse. And then, on the other side, I noticed this tall man. I think he may have been Egyptian, but I don’t know… very tall, darker features, beautifully dressed (in that layered way the French do). He was with two others, and they were talking, but he was looking straight at me. Staring. I’m maybe eight metres away, maybe even ten. I look back at the horse, and he’s still just fixed on me. And in the liminality of this event, the pinprick is already there. He walked over to me, and with one finger outstretched, he touched me just above the left nipple. And he said ‘viens’. It was the familiar form, of ‘come.’ He was standing about half a metre, arm outstretched and looking straight at me. And I was thinking, what the fuck? Then he turned and walked to the opening at the other side of the courtyard. And he passed through the arch which led into the next courtyard. And for a second, I thought, this is like a bifurcation moment—where all of life passes through something tiny. A threshold. The sound of ‘viens’ is made deep a the back of the throat as if it were inside the body, and I repeated it to myself, then paused, overwhelmed. And then I followed. Just as someone was clicking people into the courtyard with a counter someone else was clicking as people left. But just as all liminality passes through a singular point, a fingertip on my chest, a point I can still feel, so too might all of the hard hit of the geohistoric real. As I followed, the man at the door with the clicker goes click, click, click, and then, ‘attendez’ (stop). And instead of following, I was held in this space by a ‘click’. By the time I was allowed to proceed, the man I was to follow was lost to the crowd and the night.

So, all of life passes through something as tight as shrapnel—something like shrapnel in the brain—or the point of an outstretched finger. And then it’s also being stopped by the same mechanism. The click of something. Architecture is often like this. It's the door, the handle, the threshold, the passing through, the button. Yes. It’s tiny. These geohistoric sorts of moments. Moments of being completely held in place, and moments of drift, or moments of both. If I want to imagine, or if I want to think seriously about something, I have to sit, sit at my desk, feet on the ground, my chair in the right position, my computer where it is, everything laid out. And I have to be completely anchored, secure, in order to be liminal. It’s just the world, fading and focusing. You zoom into one thing and zoom out from another.

Nuit blanche, Paris. Image from https://thegoodlifefrance.com/nuit-blanche-paris/

Constant movement, constant motion, zooming in, zooming out. I’m wondering how that operates in your design process. Do you consciously work with this shifting of scale or point of view? And when you begin, whether writing or designing, where do you start? From a zoomed-in detail? Or from a larger conceptual frame?

The funny thing is, when I write or theorise or design with architecture, I start with something highly particular. That is a particular balustrade, or a particular person, a thing, or an object, or a painting, or a concept… whatever it is, it’s something that's specific. And I have to really know the specific. The question of what specific thing I’ll start with tends to be a matter of intensity. I'm looking for, only, only ever, maximum intensity. Maximum intensity is always the thing I can know. If in a moment, I’m intensely drawn to a concept, I’ll start there. Start with loving it.

This is perhaps why, in anything I write, there's a repeated pattern. You can notice that the first sentence always has a sort of strange intensity to it. And it's because I'm starting with the thing that really grabs me. And then it becomes almost like a centre of gravity. In architectural design, it's often that there's a sensation, or a conceptual idea, or a sound, like a piece of music, or something that completely ascends as a sort of high point—somewhere between concept and life. Something almost phenomenological, or abstract, or the pinpoint between them. But it has to be the most intense. When designing, everything also starts with that. So, if I'm designing anything, like the deck at the back of my house and the outdoor shower that it holds, it starts with the intensity of fucking in the shower under the trees and in the sunlight. It’s because this is the most intense thing I want to construct at that moment. The perfect outdoor bathroom then rises to the occasion of the highest intensity. I know exactly how that's going to be, exactly where that's going to happen. And everything has to form around it. Because when I do that, then I know where I stray from the intensity. I won’t write or design something that moves away from the most intense point, my aim is always to engorge it.

Yes, exactly. And what I understand from what you’re saying is that it's not a fixed concept or single idea that drives the entire project, written or not. It’s more like a trigger, like a matricial force that sets things into motion. Almost like the first hit in a row of dominoes, it activates a sequence.

But it needs something that holds it all together, something that repeats itself letting things unfold without losing coherence.

Yes, so it never runs amok. The only way it can keep moving, can go somewhere, is if it becomes more intense, right? Because otherwise, I'll retract. The intensity becomes a sort of throbbing centre of gravity. When I was writing my doctoral dissertation, there was a piece of music, it was the Kronos Quartet, Howl USA album that held the intensity. And this music is incredibly charged. It’s politically poised, and violent, edgy, and to write the dissertation I had to have that playing for about two years. I couldn't write with anything else because anything else seemed less intense—and less-intensely aligned with the writing. In a case like this I could let the intensity be held in the air, in the sound. Bare Architecture was written with Ludovico Einaudi, the L’onde work playing and it because of the pace of the book, but also started to play into the content. The music led me to Virginia Woolf and folds and waves and all types of association. It just had something in it that allowed me to centre. At other times it’s not music. It can be a painting. A sentence. An event. A stairway. A concept. A gesture in text and outside it.

These things are like Winnicott’s transitional objects. They are the things you can have and hold, but that also propel you.

Yes, I completely relate. I have the same kind of obsession. Whenever I write, I either start with the same song or listen to one track on repeat. It creates a kind of emotional consistency, puts the mood on.

Yes, and that emotional consistency isn’t always your own. I think when we design or write we do so as conceptual personae. We tend to operate a design or literary or artistic work in shifting who we are. I read things in a voice that isn’t my voice. My partner at the time was a speech pathologist, and when we moved to England, where I got a job lecturing, I hadn’t really felt the weight of my accent before. But I felt it when I started working. Almost all the students were from the southeast of England, from wealthy backgrounds, and I realized: oh, I sound very Australian. Very Austrayyyan. So, my partner attenuated my accent. Now, there’s a lecture voice, a home voice, a phone voice, and a special voice for when I speak to my mother, but there’s also a book-by-book voice, with variations, chapter by chapter. A way of being, of speaking, that aligns with the text. It’s an inhabiting of a kind of conceptual persona.

It’s something between a conceptual formulation and a material presence; you live into it. You need a figure, and it can’t be you. Well, it definitely can’t be me… because I wouldn’t know what that is. But I can step into different rooms, different registers as different people. It’s not about occupying a different physical space, it’s more than that. Last week, I was visiting psychiatric institutions, and I spent time at ST Alban and at La Borde, which I’d always dreamt of visiting. So many of the thinkers I love have passed through there. For so long, I had only had images of these places, one or two photos on Google. But going there, actually being there, changed everything. And interestingly, I was traveling with people who’ve worked in institutional psychoanalysis and psychotherapy for years, and even they hadn’t been. It changes everything, massively. Your sense of the place, of what’s happening, or what might have happened, completely shifts. Your sense of the conceptual, the textual, it all gets reconfigured. And one of the key things it shifts is you. These places might occur in voices in future work.

Charles Vitez, Flore Pulliero, Julie Van der Wielen, Anthony Faramelli and Chris at La Borde, 2024.

Yes, I think what you’re describing touches something fascinating to me. That moment of returning to a thing, even if, like in this case, the returning refers to a perceptual image built upon readings. This re-encounter reconfigures our conceptual frameworks. The material and the abstract start folding into one another.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about the power of second encounters. The first time we meet a place, or a person, through immediate or mediated interactions, there is a kind of enchantment, almost like a 'love at first sight' effect. But the second encounter does something else. I like calling it unwilding, not as a loss of intensity, but as a slow unfolding, a deepening. A kind of sedimentation, where things start to reveal their structure, their contradictions, their edges. It’s about something opening up, something becoming more complex, more inhabited.

So, I wonder if you see architecture as a process of returning, of re-encountering. So, not just as a setting for experience, but as something that transforms with us, that invites us to reconfigure what we thought we knew.

I’ve come to a position, which is something like: we can love anything, and we can be entranced by almost anything. And it's got something to do with love, and lovers, and spaces; and architecture is the same. And art is the same. It's like, what you think of something, sometimes the first time you encounter it, can find itself reformulated or reconfigured. What Pierre Klossowski calls an ‘obsessional phantasm’ is something that returns. A place we keep returning to. A sensation that keeps coming back, that stays with us, repeating in the mind just as it repeats through what we encounter. And with that repetition, that reiteration, there’s also a shift, a transformation. Something subtle begins to change each time it returns.

Maybe it’s worth bringing in the question of play, especially in the context of all these constraints we’ve been talking about. Because play doesn’t happen in the absence of rules. You need enabling constraints, a framework, something that holds the space of the game. But playfulness begins when something shifts, when other rules or norms, societal maybe, are stretched, bent, or undone during play-time. For example, because we mentioned the tool-weapon, I'm thinking of how so many games involve a kind of mock violence, like me fighting with my sister when we were kids. There’s pleasure and tension in that ambiguity, in that negotiation of force and form.

So, I wonder, can we think of architecture, or design more broadly, as something that courts this kind of edge. Do you think that we, as architects, should engage in this kind of play, where the rules are pushed to their limits, and structure and control create the conditions allowing for intensity, or even danger, to emerge? As ‘play’ I understand a form of pushing a system to its threshold, to the point where it might briefly become something else.

I think we do play incessantly. It’s a game with subtle rules though and it’s easy to get it wrong—to overstep the mark—to actually bite your sister. Whenever I'm running a project with architecture students, and I might have 20 students designing the same thing… what will happen at the end of a semester is someone (x) will come to me and say, ‘I looked at all the criteria that were written out, and the schedule of areas, and the rules about how many laboratory spaces were needed, and how the air exchange system needs to work, and the floor areas, and I met everything, I did everything. So why on earth did I only get a pass mark?’ And the answer is in their very question. It’s because this student x did everything as if everything were equivalent, as if there were an equivalence between these things.

It's not that the rules and the areas and the function are not important. But what we do in conceptual design—especially in conceptual design—but also in other design modes, is to consider all these things, as secondary to the actual thing being pursued… the actual thing that is pushed to a threshold. I can design a church or a gallery by adhering to the rules and answering all that can be written in a brief… but if the real thing I was trying to do was to push stone as close as I can toward heaven… then I’m really doing something! It’s the thing you’re doing to the nth degree that matters, the gesture from which everything else starts to fall into place, into its thrust. We might think of the Northern or Gothic line story. To run a line to heavens. It’s hard to do. It involves pushing material to a very particular extent, right to the point where it's almost dangerous. Collapse, breakage, that kind of thing. But that's also what we value in architecture all the time. The unlikelihood of Lacaton and Vassal’s Palais de Tokyo gallery interventions, or a Gothic cathedral. Just completely unlikely. Just crazy. Brilliant crazy. And ‘good architecture’ has that sort of impulsive thrust, but then someone is careful and creative enough to make it, to develop the construction detail, to manufacture the door handle, and pursue it in the thousand different ways that come to constitute it. Yes, it’s almost like a play or a game—in this case with gods and the sky itself.

Yes, I totally agree. And I’m just thinking about what you described with your student. Sometimes, we treat architectural design almost like following a manual. As if doing A, B, and C, checking all the boxes, should lead to a guaranteed outcome. And if we repeat the process, we assume we’ll get the same result again.

But of course, that’s an illusion. Even manual processes carry symbolic weight, and design is never neutral. There’s always something else happening, something irreducible. So, how do you see the relationship between process and affect?

When I think about such a relation, the word ‘courting’ comes to mind. Between process and affect, it’s a type of courting. And when I say courting or refer to courtship it’s both about the shared understandings (contracts and the like) and the rules, but it’s also very much about how one exceeds them. If I were courting someone, I’d be highly attentive to all the polite and genteel signs, but in order to overspill them all in joyous excessive encounters. In this sense even rules are riddled with eroticism and have an odd sort of magic to them. Sometimes the game is to contest them, or finding their edges, and sometimes it’s about just loving the rules that you make, the rules you know, the rules you abide by.

I think that’s what Bernard Tschumi talks about when he invokes the masochism analogy, which is: the tighter the knot, the greater the restraint, the higher the level of pleasure. We confront this zone of intensity (and want to call out ‘Oatmeal’) often in architecture. I negotiated this intensity and almost left architecture school in my final year. I wanted to achieve something brilliant that year. And it was going to be theoretically astute, drop-dead beautiful, with just the right bite or edge, and contemporary, and I was working, working, working toward this. I had all the concepts in my head, the site information, the brief, and all the rules in my head, and I’d swallowed it all up. But I couldn’t do it. Or at least I couldn’t achieve what I wanted. I could pump something out that would work, that would be fine, that would pass, but I couldn’t get it right. And I said to my partner at the time, I can only do this for one more day, one more night, it’s killing me.

That night I sat at the drawing board and drew. I was meant to be designing a laboratory building, but instead I drew an air vent from above. And the air vent looked a little bit like a cat’s nose. And there was something in the geometry of that vent that was perfect. It seemed to speak about all that I’d been hoping to achieve. And from this perfect air-vent (because again so much life passes through things as small as fingers) I then drew the perfect roof for this air vent and then the perfect set of lab roofs over the next spaces and then the perfect entrance and the perfect site plan etc. Not perfect for the laboratory, or the project…. But perfect for the little cat-nose-air-vent that itself was perfect. And the project was done.

I do this with students as well now. I try not to have them start designing a building through the whole, or the mass. Instead, I get them to start with something that’s already perfect. What I say to them is: take a lover, or your mother, or someone you're super close to, or someone you really want to know. And start with that body. It doesn’t matter what the project is…. But let’s say it’s a crematorium. And instead of designing a crematorium, what you do is design the perfect surface upon which your lover’s or mother’s body might lay. Instantly everyone knows the dimensions, knows the exact material, knows the position, knows where the sun would be at that time of day. And from there they know where the body is relative to an entrance to the space, where they sit, where they parked a car and how they approached the crematorium. Done.

There’s a perversity to this, I know. But I like it. The difference between a pervert and a fantasist, in Freud’s sense is that the fantasist just dreams whereas the pervert makes it happen. And that’s the architect. They don’t just dream of things. They’re going to make this. This will be.

Chris L. Smith, Loved, Sydney 2012.

Yes, exactly. And I’m thinking that in the process of speculation what really matters is how we ask questions in the first place. It’s not about asking ‘what is it?’ as if there’s a fixed answer. You don’t ask in general. You ask why. You ask with whom. It’s more like: how do you approach a question so that it becomes an expression of the problem itself?

In architecture studios, you are often dealing with other people, other students, and other lives. The first thing we always do, in our first session—and again it sounds perverse and alien— is always much more like group therapy. I don’t ask students sitting around a table, ‘Tell me about your education up to now.’ I ask things like, ‘Who is the most significant person in your life?’ or ‘When did you last cry?’ … And after that first session, the group functions, because everyone’s exposed, everyone’s a bit rawer, and from that point you can actually deal with what matters, rather than dealing with stupid discussions about floor-to-ceiling heights or ideal air-conditioning placement. To actually, actually speak about love, or about sex, or about death or about a visceral engagement, or about what one feels is incredibly important. It’s important because such things are bound to architecture and architecturally configured.

Yes, and coming back to where we began, this whole conversation has circled around questions of structure, constraints, play, and speculation, but what stays with me most is the idea that value in architecture, and in general, comes not from what it explains or completes, but from the way it unsettles us. Not of what it closes, but of what it opens up. Like your first sentence in Bare Architecture.

Yes, that’s right, it’s an opening, because there’s something there for me… an intensity from which a whole book might spill. I often work with the image, an image, a painting, a piece of music, whatever it is… and in that intensity is always something that I can’t completely pin down. If I could pin it down, then it’s boring. And the reason I’m talking or writing or designing, it’s not because I know what this intensity is, it’s because I don’t, or can’t know it. And in so many ways it compels me, rather than me controlling it. I’m usually negotiating a thought because it causes me to unknow something, or to not know it. It starts at that question, that raw thing. I tend not to say what something is… and am more likely to ask: why on earth is that?

So, we don’t simply state what it is… We ask what is that, and why on earth is that? Forming in a way, in advance, the intensity of what we’re trying to reach. And maybe we return to oatmeal not as clean food, but as a stand-in for all the quiet rituals that hold intensity. I think this is a fitting point to close our discussion. Thank you so much for your time, Chris. I hope it hasn’t been too exhausting for you. It has certainly been deeply enriching on my end.

Deleuze, Gilles. The Logic of Sense. Translated by Mark Lester, with Charles Stivale. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

Deleuze, Gilles. Difference and Repetition. Translated by Paul Patton. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem and Helen R. Lane. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia 2. Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Volume 2: The Use of Pleasure. Translated by Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage Books, 1990.

Klossowski, Pierre. Living Currency. Translated by Vernon Cisney, Nicolae Morar and Daniel W. Smith. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

Juarrero, Alicia. Context Changes Everything: How Constraints Create Coherence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2023.

Perec, Georges. Species of Spaces and Other Pieces. Translated by John Sturrock. London: Penguin Books, 1997.

Smith, Chris L. Bare Architecture: A Schizoanalysis. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

Smith, Chris L. Architecture After Deleuze and Guattari. London: Bloomsbury, 2023.

Tschumi, Bernard. ‘Advertisements for Architecture, from Bernard Tschumi, Architecture Concepts: Red is Not a Color, New York: Rizzoli, 2012.